Vakkom Moulavi, Modernity And The ‘Islahi’ Movement In Kerala – Analysis

By K.M. Seethi

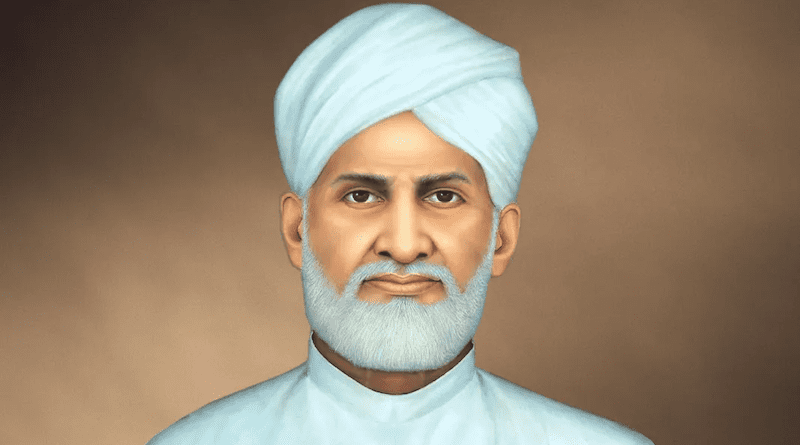

This article is written in commemoration of 150th Birth anniversary (28 December) of Vakkom Moulavi who played a major role in modernizing the Muslim community in the South Indian state of Kerala.

‘Islahi’ (Reform) Movement

Vakkom Mohammed Abdul Khader Moulavi (1873-1932)—a scholar-reformer widely known as Vakkom Moulavi—was a pioneer in the making of modern Kerala, the south Indian state which witnessed the advent of three Semitic religions centuries back. Islam reached the shores of South India more than twelve centuries before. However, the social and religious profile of Muslims in the region presented a very complex character, unfolding itself in different practices and traditions. Most of such traditions were embedded in local practices and rituals—obviously influenced by the native cultural mores—though the Islamic precepts continued to lead their life world.

Over centuries, the Muslim community developed a certain resistance to the currents of modernity, which held them back in different walks of social spheres. They were also influenced by colonial and imperial rule in different ways. The challenges before them were therefore manifold and cumbersome.

The social reform among the Muslims of Kerala has a history of more than a century though it did not have a uniform, unilinear character as a result of the particular conditions under which Kerala emerged. The experiences of south Kerala (Travancore-Cochin) and north Kerala (Malabar) differed, as they had undergone different socio-historical processes and changes.

The Muslim reform process in Kerala extending over half a century since the 1880s had different engagements with modernity–-from accommodation within the colonial modernity to expanding concerns of nationalism and the politics of bargain within. The leading stream of the reform agenda among the Muslims was led by Sanahullah Makhti Thangal (1847-1912), Vakkom Abdul Khadir Moulavi (1873-1932), Sheikh Mohammed Hamadani Thangal (died in 1922), Maulana Chalilakathu Kunjahammed Haji (1856-1919), K. M. Moulavi (died in 1964), et al. under the Islahimovement. They addressed many critical issues of religion and society, thereby taking up the challenges of modernity most profoundly. They were critically engaging themselves with the enlightenment practices through organizations such as Mohammadiya Sabha in Kannur, Chirayainkil Thaluk Muslim Samajam, Lajunathul Mohammadiya Sangham in Alappuzha, Muslim Aikka Sangham in Kodungallur.

The Muslim reform movement in Kerala, as it gained momentum till the early thirties, did not seek a mere “return to the Islamic pristine purity,” as depicted by some, but it was forward-looking, critically, and constantly engaging with the challenges presented by modernity. For instance, Makhti Thangal, the pioneer of Muslim reform movement, began his career as a British official but opted to remain in the realm of Islah, seeking to engage with modernity. On one end of the spectrum, he confronted the Church missionaries who propagated a highly distorted image of Islam; on the other hand, Thangal exhorted the Muslims to come out of their social seclusion to undertake English education (besides in their mother tongue, Malayalam) and through it the emerging challenges of modernity. Makhti Thangal was not anti-British in essential character, just as Sir Syed Ahamed Khan was during this time, but sought to uplift the Muslims from their self-imposed backwardness and to prepare them to face the challenges of modern times.

Vakkom Moulavi’s Islahi movement, which traversed over three decades of the early 20th century, was addressing the challenges of modernity and the critical issues presented by the enlightenment paradigm. The very launching of Swadesabhimani (Patriot) in 1905 heralded the beginning of this engagement. Moulavi’s Swadesabhimani was the first newspaper in Kerala that established communication links with the London-based Reuter. The press itself was imported from England. Those who would talk about Swadeshabhimani Ramakrishna Pillai seldom mention the moving spirit behind it and the symbiotic relationship that prevailed between Vakkom Moulavi and Ramakrishna Pillai. Ramakrishna Pillai used Swadesabhimani as an instrument of radical criticism of the imperial rule in the state of Travancore which eventually led to its closure, and confiscation, and the editor Pillai was sentenced to transportation. The closure of Swadesabhimani did not detract Moulavi from pursuing his other objectives.

While the Islahi movement was profoundly social, it also exhibited its politico-religious commitments. It was essentially anti-colonial in character, yet it did not seek to offer any Islamic alternative in political terms. Instead, Vakkom Moulavi’s major initiative was to liberate the Muslims from the morass of self-delusions to which they had fallen for so long. But this should not be interpreted to mean a mere ‘purification’ campaign, as argued by some, calling for a return to the pristine purity of the holy texts. Moulavi had an entirely different approach to the importance of the holy texts, which exhibited both hermeneutical as well as social foundations. Both were combined in the very principle of ijtihad, to which he was profoundly committed. The principal aim of the Islahimovement should therefore be kept in perspective. It was primarily a call for engaging with modernity, and the Muslims were called upon to come forward to understand both religion and modern society in dialectical terms, not to the level of discarding one in favour of the other. Most historians tend to ignore this, for one reason or other.

Those who underestimate Vakkom Moulavi’s Islahi movement try to disregard its inherent potential as such. His basic position on religious reforms centres on the concept of ijtihad. Moulavi strongly argued that the door of ijtihad couldn’t be closed. He exhorted the Muslims to rediscover and reinstate ijtihad, the principle of independent judgment with a view to rebuilding the shariat in the light of modern thought and experience.

Moulavi’s adherence to the Islamic hermeneutical tradition could be seen in his insistence on individual ijtihad, which was not only permitted but was essential to arrive at decisions where the holy texts were either ambiguous or silent. His perspicuous analysis of the laws of Islam further provides evidence of his rational approach. Even while affirming that “the laws of Islam concerning spiritual matters are eternal,” he strongly argued that “the laws of Islam concerning temporal matters are not immutable, and hence depending on the conditions of time and place, they are subject to change,” The most radical of his views can be seen in his perspectives on the Islamic laws.

Vakkom Moulavi said that the Muslims should address their socio-economic problems even transcending the four schools of Islamic jurisprudence if they were unable to equip them. Obviously, the Islahi movement Vakkom Moulavi, carried on for three decades, did not seek a mere pilgrimage to the past, but it was a progressive engagement with modernity. It addressed not only the questions of laws and beliefs in Islam but took up challenges of modern education, including women’s education, gender justice, rational outlook on social and religious matters etc. Needless to say, very few ulama could accept Moulavi’s exegesis concerning spatiotemporal matters. That is why he had to face stiff opposition from orthodox elements who were only concerned about the scriptural matrix of Islam, besides keeping the community in perpetual ignorance and superstition.

Even as Vakkom Moulavi’s Islahi movement got underway (in the most dynamic way with multiple agenda of reforms), traditional Mullahs rose in revolt against the mission he had set in motion. They obviously did not have any scholarship or any sense of the implications of modernity. This led them to initiate a counter-campaign even calling Vakkom Moulavi ‘kafir’ (infidel/disbeliever) and ‘Wahhabi’ (a derogatory term used against Mohammad Ibn Abdul Wahhab and his followers). It is true that Moulavi had written about Wahhab (as part of cataloging the reform efforts in Islamic history) pointing to his mission of ‘purging’.

But Moulavi never considered himself a Wahhabi. Rather many of his modernist views were derived from the writings and perspectives of Al-Ghazali (whose Kīmyāyé Sa’ādat [The Alchemy of Happiness] he translated into Arabic Malayalam), Muhammad Abduh of Egypt (whose ‘Al-Manar’ had deeply influenced him), Shah Waliullah (1703–1762) Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī (1838-1897) and Syed Ahmad Khan (1817 -1898). A common thread of all these traditions is the humanism embedded in Islam and its potential to engage modernity and all its challenges.

Moulavi’s movement saw positive results when there was general receptivity to his call. However, since the early 1930s, it did not progress further in a wider realm due to the particular circumstances imposed by nationalist politics, on the one hand, and the politics of communal bargaining, on the other. The gains of the social reform process could not be consolidated in the emerging scenario of inter-party struggles, particularly of the Congress-Muslim League tussle.

Meanwhile, the situation created by the absence of strong leadership, after Vakkom Moulavi, was soon to be appropriated by the more orthodox Ulama. The most long-lasting setback of the reform process started in the late 1950s when all religious and communal forces arrayed themselves against the democratically elected communist government in Kerala under the banner of vimochana samaram (liberation struggle).

Ever since, the successive governments in Kerala have been engaging the religious and communal forces in the state, most strategically, in the electoral process. Caste-based, religion-based, community-based organizations began to gain strength across the world in the early 1980s. Kerala society, having been exposed to these influences in a variety of ways, could not escape from the emerging scenario of caste/communal consolidations. The achievements made over the last century, through the valiant efforts of reformers like Vakkom Moulavi, seem to be waning amid such cross undercurrents.

An early version of this was presented in a seminar at the University of Calicut, which was later brought out by Countercurrents.

Unbelievable that a person like Vakkom Moulavi lived and led a life of dedicated mission in Kerala in early twentieth century. He is symbolic of fearless journalism and emancipatory social action. But does his legacy get perpetuated today, by his own followers? His message of life is a reminder to fundamentalists and fanatics in modern Islam.

A scholar of Islam with profound democratic credentials, indeed.