Kosovo War Crimes Court’s First Trial To Set Precedent – Analysis

After a six-year wait, the first trial at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers in The Hague will open on September 15, with former Kosovo Liberation Army officer Salih Mustafa facing charges of illegally detaining, torturing and killing prisoners.

By Xhorxhina Bami

It was announced last week that the first trial at the Kosovo Special Chambers in The Hague will open on September 15 – almost a year after the prosecution made its first arrest in the Kosovo capital, Pristina, and more than six years after the court was established.

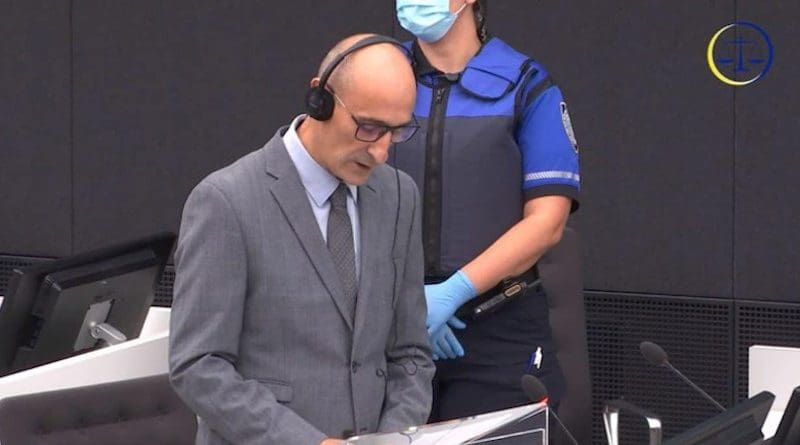

Former Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA officer Salih Mustafa will appear before the court which was set up to try former KLA members for alleged crimes committed during the Kosovo war from 1998 to 2000.

The Specialist Chambers are part of Kosovo’s judicial system but are located in the Netherlands and staffed by internationals.

They were set up in August 2015 by the Kosovo parliament, acting under pressure from the country’s Western allies, who believe Kosovo’s own justice system is not robust enough to try KLA cases and protect witnesses from intimidation, after previous cases at the UN’s Yugoslav war crimes court in The Hague were marred by witness-tampering.

Mustafa’s indictment was confirmed on June 12, six months after he became the first KLA suspect to be arrested and transferred to detention in The Hague to await trial.

The lead prosecutor in the case, Jack Smith, said in October 2020 that he will call at least 15 witnesses to testify against Mustafa.

Mustafa, who was a commander in the guerrilla force’s wartime Llap Operational Zone in north-eastern Kosovo and was also known by his nom de guerre ‘Commander Cali’, has pleaded not guilty.

His trial, which might last for over a year, will set a precedent for the rest of the KLA cases, experts told BIRN.

‘Joint criminal enterprise’ claim causes outrage

The indictment charges Mustafa with “arbitrary detention… cruel treatment … torture … and murder” of civilians between “approximately April 1, 1999 and around the end of April 1999”.

It alleges that he was part of a joint criminal enterprise uniting “certain other KLA soldiers, police, and guards”, which had a “shared common purpose to interrogate and mistreat detainees”.

Kosovo media and lawyers have interpreted user of the term ‘joint criminal enterprise’ as an attack on the KLA itself, claiming it can be seen as a suggestion that the KLA was a criminal organisation.

This interpretation has fuelled resentment among Kosovo Albanians, many of whom see the so-called ‘special court’ as an insult to the KLA’s liberation war against repressive Serbian rule.

However, Amer Alija, a coordinator and legal analyst at the Humanitarian Law Centre in Kosovo, told BIRN the claim that there was a joint criminal enterprise should not “be interpreted in the context of the Kosovo Liberation Army because not every KLA soldier or member is responsible for the crimes committed by a soldier who has not complied with the rules of war”.

Alija said that suspects can be judged to have participated in a joint criminal either by the actions – by “directly ordering or participating in violations” – or by their inaction – “by being the soldiers’ of the soldiers and being aware that… war crimes were being committed” but taking no action to prevent or sanction the crimes.

The indictment in the Mustafa case claims that detainees were held at a KLA compound in the village of Zllash/Zlas and deprived of food, water, sanitation, hygiene, bedding and medical care, and were subjected to “beatings with various instruments, burning and the administration of electric shocks”.

They were also psychologically tortured, “including through threat of death and serious bodily injury, fear, humiliation, discrimination on political grounds, intimidation, harassment, interrogation, and forced or coerced statements and confessions”, the indictment says.

The indictment further alleges that Mustafa often ordered other members of his unit to torture the detainees or did so himself.

Establishing a model for other trials

Taulant Hodaj, a Kosovo lawyer who is a partner at the Hodaj and Partners law firm, told BIRN that Mustafa’s trial will “create a precedent” for the court’s practices in the rest of the cases against former KLA leaders.

As well as Mustafa, former Kosovo President Hashim Thaci and two other ex-guerrillas turned politicians, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi are also in custody in The Hague, charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Pjeter Shala, whose indictment was confirmed on the same day as Mustafa’s but who was arrested in March 2021 in Belgium, is also awaiting trial. They have all pleaded not guilty.

The Kosovo Specialist Chambers is a relatively newly-established court and its procedures have yet to have been put to the test in a trial.

“Being a new court, there will be delays and many complaints by the defence… because developed practices do not exist yet,” Hodaj said.

Even before the first trial has begun, defence lawyers have already accused the prosecution of not properly disclosing evidence and causing delays that have hampered their cases.

Based on previous war crimes trials, the trial against Mustafa is likely to last more than a year.

For the defence to succeed, it needs to reject all the testimonies and evidence provided by the prosecution, usually by introducing alibis, Alija explained.

“Usually in war crimes trials, the defence tries to prove the accused is not responsible by providing another suspect, who usually is no longer alive,” Alija explained.

So far Mustafa’s lead attorney, Julius von Bone, has not declared how many witnesses he will call to testify. BIRN contacted von Bone but did not receive an answer by the time of publication.

Both Alija and Hodaj said that they believe the first-instance verdict in the Mustafa trial will be handed down by the end of 2022. An appeal could then ensure that the process continues into 2023 or beyond.