The ‘Vanguard Bank’ Disputes: What Might China Argue? – Analysis

Finally – after three months of mounting tension- China’s Haiyang Dizhi (Marine Geology) 8 – a seismic survey vessel –has departed Vietnam’s claimed 200 nautical mile(nm) Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Its prolonged presence there was worrying because in May 2014—when China’s national oil corporation drilled test wells in another part of Vietnam’s claimed EEZ – China and Vietnam coast guard and fishing vessels rammed each other and anti-Chinese riots broke out in Vietnam.

In this latest confrontation, Vietnam’s foreign ministry repeatedly accused the vessel and its coast guard escorts of violating Vietnam’s sovereignty. Vietnam’s coast guard shadowed the Chinese vessels and demanded – without effect – that the ships immediately leave Vietnam’s EEZ. https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2019/10/24/world/asia/24reuters-vietnam-southchinasea.html; https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3034383/chinese-oil-survey-ship-finally-leaves-vietnam-controlled This temporary lull in tensions provides an opportunity to look more closely at the situation and the positions and options for both sides.

Despite Vietnam’s righteous indignation, this case is more complicated than an egregious violation by China of Vietnam’s EEZ and continental shelf. Arbiters might well determine that Vanguard Bank and the immediate surrounding area belong to Vietnam. But this has yet to be determined and this assessment does not extend to Vietnam’s entire claimed EEZ and shelf.

China has been—with words and now actions—demanding that Vietnam’s contractors cease exploration and exploitation pending negotiations between it and Vietnam. China claims at least the outer parts of it and has put out blocks for lease that overlap Vietnam’s already leased petroleum blocks 128-132 and 145-157. Four off these blocks are already producing oil for Vietnam and some others are in the process of doing so. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/05/25/world/chinese-claims-south-china-sea-overlap-vietnams-oil-projects/ According to a 24 August 2019 Open Letter from the President of the Viet Nam Society of International Law to the President of the Chinese Society of International Law, China has stated that “the operation areas of the survey vessel HD-8 and its escort vessels are within the maritime zones under China’s jurisdiction”. China Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said the Chinese vessel was “in Chinese-controlled waters”. https://www.oedigital.com/news/472120-chinese-ship-exits-vietnam-s-waters-after-disputed-surveys

Vietnam considers China’s actions a clear violation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to which both are parties. Indeed, it is apparently considering taking China to arbitration under its dispute settlement mechanism.

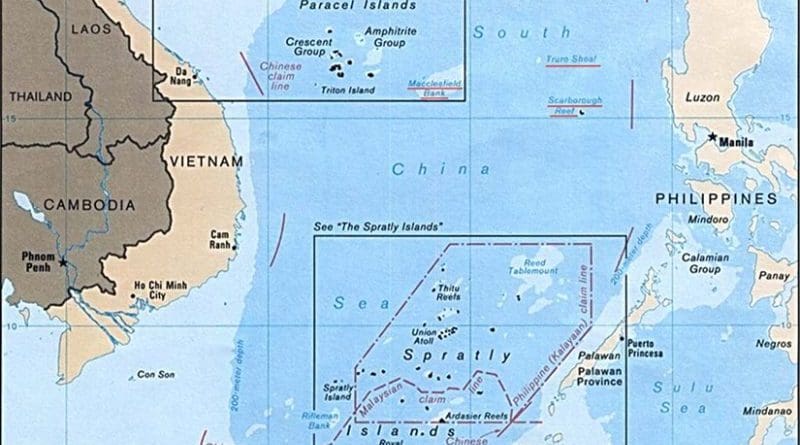

The basis for China’s claims is ambiguous. The China-Philippines arbitration panel ruled that China’s nine-dash line historic claim is not compatible with UNCLOS. It also ruled that all of the high-tide features in the Spratly Islands are “_ _legally rocks for purposes of Article 121(3) and do not generate entitlements to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippines_v._China

So what might China argue? It might say that technically, the ruling on the legal status of the Spratly features applies only to those examined and named by the panel– and it does not apply to the Paracels—at least directly. Moreover, the general applicability of this particular ruling was – and still is – very controversial for other countries, the U.S. in particular. They stand to lose to the high seas and thus the “international community” some of what they claimed were their resources in EEZs and continental shelves extending from features similar to those in the Spratlys. They would thus like to see that decision reversed. It is quite possible that a different panel in a different context would rule differently.

China claims among others the fourth largest feature in the Spratlys – Spratly—which lies about 200nm to the north east of Vanguard Bank and is occupied by Vietnam. The status of Spratly was not examined or determined by the panel. If China owned the Spratly feature and it was ruled a legal island, it could generate a 200 nm EEZ and a continental shelf extending as far as 350 nm from legitimate baselines. Of course such claims would overlap similar claims from other nearby high tide features and have to be sorted out legally and politically. Most important, boundaries between China and Vietnam would need to be established. Ordinarily, such a boundary would be closer to the island than Vietnam’s mainland. Indeed, precedents suggest that an opposing island would get very little EEZ and shelf versus a mainland. But that is unknown in this specific case.

According to the U.S., Vietnam uses an excessive baseline that extends its EEZ and continental shelf in this area further than allowed by UNCLOS. https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/58573.pdf Moreover, equitable principles would play a role in boundary delimitation– and that is a crap shoot. For example, China might argue that it has the greater need for the resources based on its greater population. As long as the status of Spratly is unknown and until a boundary is determined, the area is disputed and according to the Guyana-Suriname precedent, neither country should unilaterally proceed with exploitation. https://academic.oup.com/jids/article/10/1/160/5133609; http://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_XXX/1-144.pdf This means China might argue that at least the eastern portion of Vietnam’s claims in that area is disputed and its China’s request that Vietnam have Spain’s Repsol and other foreign oil companies cease their exploitation activities in the area may be reasonable.

China might also argue that the Paracels belong to China, that they are legal islands, and that they generate an EEZ and a continental shelf extending out to 350 nm. Those claims could encompass some of the northern part of the area in contention and again necessitate the establishment of boundaries.

The previous arbitration result suggests that the Paracels may not generate EEZs or extended continental shelf. But again that is unknown – and at least some of the area could be legitimately disputed until an arbitration or an agreement decides otherwise.

Another concern is that there could be oil or gas deposits that straddle potential boundaries. In such a case, previous practice suggests that the two claimants should refrain from unilateral exploitation near a potential boundary and negotiate a unitization agreement so that one does not suck the oil or gas out of the other’s potential portion. Again since the boundary is uncertain, exploitation should not proceed.

If Vietnam takes the issue to arbitration, it must first persuade the panel that it has jurisdiction. A Chinese claim to part of the area based on the Spratly feature and the Paracels could complicate an arbitration panel’s acceptance of jurisdiction. According to UNCLOS Article 298, exemptions from jurisdiction include sovereignty disputes, boundary delimitation, and military and law enforcement activities. China might argue that this dispute does indeed involve one or more of these exemptions. The China-Philippines arbitration panel made a rather narrow interpretation of these requirements for jurisdiction. But another panel in another context might decide differently.

Another obstacle that Vietnam has to overcome before proceeding to arbitration is “admissibility”. There exists a China-Vietnam bilateral agreement that stipulates “for sea-related disputes between Viet Nam and China, the two sides shall settle them through friendly negotiations and consultations.” Whether this would apply and prevent the panel from proceeding depends on the status of this “agreement”. If it is considered formal and binding, it will carry more weight with the panel than the Declaration on Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea that the previous panel dismissed as only a “political statement’ and thus did not prevent “admissibility”.

It is by no means certain that the panel will accept jurisdiction and admissibility.

But the decision for Vietnam’s leaders to pursue arbitration against China is more political than legal. They have to weigh the advantages and disadvantages.

If its complaint passes the procedural hurdles and is finally victorious, the advantages are that it will satisfy Vietnam’s nationalists, recover some lost pride, credibility and legitimacy for the government, and bring international law to its side – for what that is worth in these days of increasingly raw power politics.

But the practical disadvantages far outweigh the theoretical advantages.

First, even if the panel decides it has jurisdiction and that the complaint is admissible, Vietnam may not ‘win’ on all points. In other words, it is possible that Vietnam will lose part of its claimed EEZ and shelf. Second, even if it does ‘win’, the ruling cannot be enforced as we have seen with the Philippines-China arbitration result.

Third, and perhaps most important, by ‘internationalizing’ the dispute, Vietnam will have alienated and angered its permanent giant neighbor with whom it must live into the indefinite future. This action would also probably not be looked on as helpful by the rest of ASEAN which Vietnam is to chair next year. It will likely suffer economically, politically, and possibly militarily. So Vietnam’s leadership would have to decide if it really wants to confront China on the international political stage on this issue. Some have suggested that Vietnam should move closer to the U.S. to counter China. But does its leadership really want to side with the U.S. – a declining power –against China – its permanent neighbor and inexorably rising regional and world power?

Such claims by China may not eventually be successful. But they may raise the possibility that there is a valid dispute over at least part of the area. In sum, Vietnam has the better argument for its claim to Vanguard Bank and much of the larger area in question. But if China can demonstrate legally plausible claims to part of the area, then it may make Vietnam think twice about proceeding to arbitration and continued drilling, and create sufficient leverage to persuade it to negotiate bilaterally. At the very least it would gain time – – which is to the advantage of the ever burgeoning China.