Ansar Al-Khilafah In The Philippines: Name Change Rather Than Game Changer – Analysis

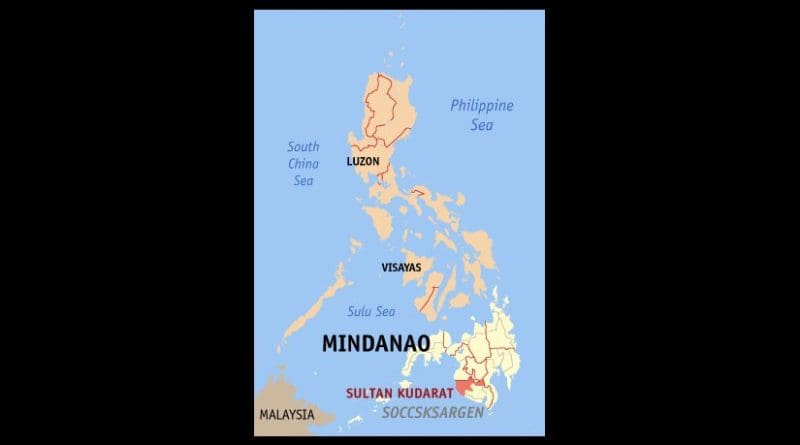

On November 26, 2015, eight (8) members of the Ansar al-Khilafah in the Philippines (AKP), including an Indonesian national were killed in a joint law enforcement operation by the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the Philippine Marine Corps in the town of Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat province. The site of the clash, on the Mindanao mainland, was far from the usual stomping grounds of Islamist terrorist groups in the Philippines. The skirmish had been deemed by some pundits as a strong indicator of the arrival of the Islamic State (IS) or Daesh in the Philippines. However, this assertion is weakly supported by the socio-economic conditions in the southern Philippines. Instead of being a game changer, the AKP appears no different to other private armed groups (PAGs) in Mindanao who present an ideological façade to cover their criminal acts.

AKP Pledges to Daesh

SITE Intelligence first reported on the pledge of allegiance by the AKP to Daesh in August 2014. The group, claiming to hold sway in Saranggani province, appeared as a distinct entity from the Muslim secessionists in central Mindanao (the Moro Islamic Liberation Front [MILF] and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters [BIFF]) and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in western Mindanao. The short 5-minute video showed a group of armed men, wielding weapons common to the private armies and militias in Mindanao, offering their bayah (pledge) in front of black banners associated with Daesh. This development was deemed by self-styled terrorism experts in Manila as proof positive of the ideological influence of ISIS.

But aside from this superficial demonstration of fealty credible evidence did not indicate operational link between the AKP gunmen and Daesh. For one, a bayah should be a reciprocal act between Daesh “central” and the purported Caliph, and those who pledged. Haphazard pledging as executed by the AKP further indicates the lack of awareness for Daesh’s own jurisprudence and practices. This ignorance of Islamic jurisprudence (the Deash’s purported version) underscored the unideological bent of Islamist militants in the Philippines. This one-way pledge was also consistent with the practice of the jihadist milieu in the Philippines, who seem to pledge allegiance to whichever international group was on the news, be it Jemaah Islamiyah or Al Qaeda in the previous decades.

All Conflict is Local

The life trajectory of Mohammad Jaafar Maguid (aka Commander Tokboy), the alleged leader of the AKP, is thus no different from the other former Muslim secessionists in Mindanao. Maguid was reportedly a member of the MILF, a secessionist group which had already signed a peace agreement with the Philippine government in March 2014. Taking a hardline stance against the talks, it would appear that Maguid was able to cajole former MILF members, and other armed but unaffiliated fighting age men to build the AKP. It can be argued that instead of being a trailblazer, Maguid was a latecomer to the post-MILF era, which saw the emergence of localised insurgent groups such as the BIFF.

In the absence of direct operational support from Daesh, the act of bayah only has one useful function for groups like the AKP—to create an image of ferocity for criminal activity. An inflated image for AKP allowed it to extort money from local businesses and to operate organised rackets like cattle rustling in the fertile agricultural areas of central Mindanao. By alluding to ISIS links, AKP members were able to strengthen their brand, even with their small personnel strength of around 20-50 armed members. Compared to private militias or armed clansmen in Mindanao with hundreds in their ranks, the AKP’s actual operational capability would be a drop in the bucket.

Prior to the 26 November clash in Palimbang, the AKP did not even engage in armed activities against the usual military or civilian targets, in contrast to Islamist groups such as the ASG and the BIFF. Neither were they capable of the cross-border kidnapping raids some factions of the ASG had launched against East Malaysian resorts. AKP initiatives were for profit-generation, extorting local farmers under the threat of IED attacks. It was the charges of banditry, not terrorist acts, which led the PNP to launch an operation against AKP. This very localised and parochial orientation, necessary to sustain the AKP’s day-to-day existence belies its grandiose claims of affinity to Daesh.

Denying Discursive Space to Daesh Imitators

The biggest potential policy mistake for the Philippine security forces is to play to the AKP’s discursive games. The Philippine armed forces’ policy of referring to the AKP as “bandits” is an astute step to ensure that the group’s image is not unduly strengthened. While the AKP may claim to be important supporters of the purported Caliphate, the reality on the ground suggests otherwise. AKP does not possess the ideological robustness of the “early” ASG nor the operational/financial resources of the now ransom-enriched ASG.

In the long run, much could be done to diminish the appeal of AKP and other iterations of armed groups in Mindanao. Referring to the black banners favoured by jihadists as an “IS flag” is both counterproductive and erroneous. The black banner is a generic symbol of the Muslim faith, unfortunately corrupted by Daesh. Conflating such symbol of faith with a terrorist organisation would only antagonise the moderate Muslim Filipinos. All told, the Palimbang clash underscored the AKP’s weaknesses and rendered shrill its threats.

*Joseph Franco is an Associate Research Fellow with the Centre of Excellence for National Securiy and a CSIS Pacific Forum Young Leader