Jewish-Muslim Conviviality In Morocco – Analysis

Early Jews in the Maghreb

Since antiquity, Morocco has been at a crossroads of encounters for several civilizations, all have been there, the Phoenicians, the Romans, the Vandals, and the Byzantines, each of these civilizations attempted to inflict a new language, religion, and a way of life on Morocco.

The Phoenicians, a trading people whose origins lie in present-day Lebanon, needed to expand their commercial network in the Mediterranean basin and push their fleet westwards. As early as 1250 BC, they began contact with the populations of North Africa, with a view to establishing themselves there. But, it is from the flight of princess Elissa in Eastern Maghreb (current Tunisia), that all changed. The latter, fighting for power in Tyre with her brother Pygmalion, had to flee after the assassination of her husband and founded Carthage (meaning in Phoenician, a ‘’new city’’) in 814 BC, a state that tried to establish its influence as far as Iberia (modern Spain).

The early Jewish migrants came with The Phoenicians, according to historical chronicles. The first traces of a Jewish presence (Maghrebi Jews (מַגּרֶבִּים or מַאגרֶבִּים, Maghrebim)) can be found in Carthage (today’s suburb of Tunis), a city founded by the Phoenicians in the seventh century BC. Four centuries later, this flourishing port city became a rival to Rome in terms of trade, wealth, and population. (1)

From then on, Judaism was an integral part of the social and cultural fabric of the city, a group inseparable from the Christian or pagan community. This mosaic constituted the different components of the social pyramid of pre-Islamic society. (2)

Thus, the traces of a Jewish presence on the Mediterranean coast of Africa go back to ancient times. It preceded the Arab conquest and the Islamization of Africa by at least nine centuries. Inscriptions to that effect have been duly discovered by archaeologists. Indeed, there have been Jews in Morocco for over 2,800 years, longer than there have been Arabs in the area. Even in the ancient Roman ruins of Volubilis, there are traces of a synagogue. (3)

Many legends date the Jewish presence in Morocco to a period before the destruction of the first Temple. There too, the proselytizing activities of the Jews would have been deployed, who would have converted the Berber tribes to Judaism before the Arab conquest. (4)

When the Arabs conquered the Maghreb, they found there Amazigh/Berbers, Jews, and Judaized Amazigh/Berbers. Islam enabled Jews to retain their faith and practices, participate fully in the life of the city, and live in symbiosis with other communities. (5)

However, this represented two major challenges for the Jews, on the one hand, there was a new authority to which they had to adapt, and on the other, the danger of assimilation against which they had to protect themselves.

Thus, Fez became one of the nerve centers of Islamic civilization and the cradle of Judaism. (6) Over the years, the learned members of this community have oscillated between Morocco and Cordoba in Spain. Several poets and rabbis have allowed the influence of a new type of Judaism. In this sense, Haïm Zafrani specifies: (7)

[“The rabbis of the Maghreb were the masters of Spanish Judaism and the founders of the Spanish school”.]

« Les rabbins du Maghreb aient été les maîtres du judaïsme espagnol et les fondateurs de l’école espagnole »

This tradition of exchanges between the Jewish communities of the two shores of the Mediterranean continued against all odds until the very eve of the Reconquista in 1492 and the expulsions of Jews from Spain: the rabbis Haïm Gaguin and Saadiah Ibn Danan, both of whom came from Fez to varying degrees, lived for many years in Spain before being surprised by the edict of expulsion. (8)

Living together

For more than two thousand years, Jews and Muslims have lived together in Morocco and cooperated in the development of its cultural and artistic wealth. Indeed, before the advent of Islam, the autochtonous Amazigh/Berbers and Jews duly set up a common cultural scheme that is known today as: The Judeo/Amazigh Cultural Substratum. (9)

The history of Morocco embodies an exceptional case of Jewish-Muslim conviviality. Jews and Muslims have been living side by side for centuries. There has been throughout their common long history great cultural permeability largely inherited from the emergence of a political dimension in the relations between Jews and Muslims, and more broadly the relations between the various communities and minorities in society. (10)

Jews lived side by side with Muslims. This coexistence was facilitated by certain similarities between Muslim and Jewish cultures. Monotheistic, with prohibitions, both practising the rule of circumcision, and the similarities between them are numerous. (11)

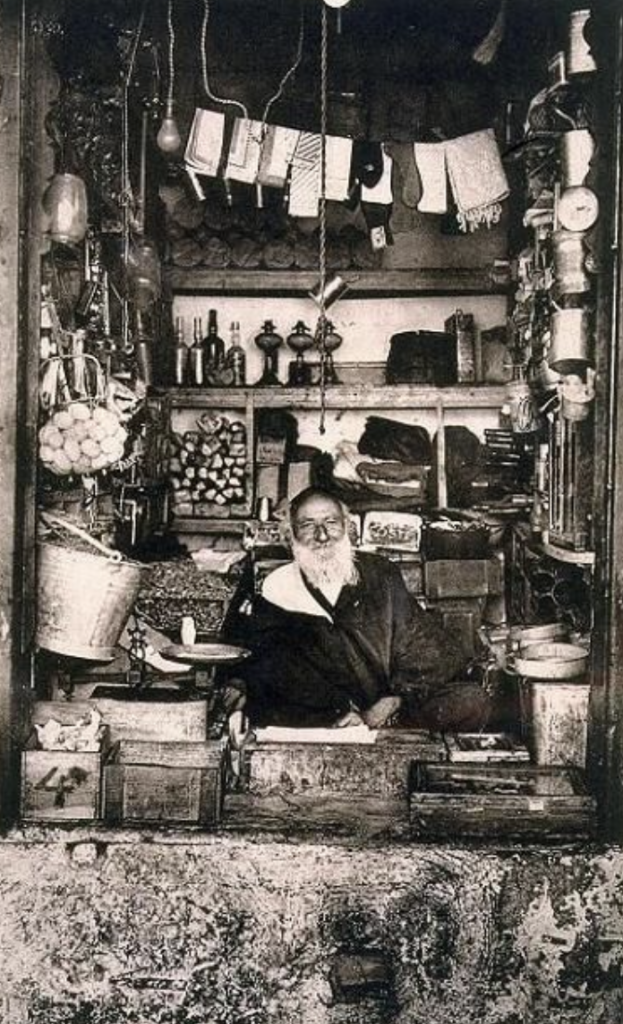

The contacts between Jews and Muslims were frequent: the latter go to the Mellah to make purchases, sell their own products, borrow money, deliver shares of the harvest to their Jewish associates, use the services of seamstresses or have watches and jewelry repaired. Some Muslims even had shops in this neighborhood, including stalls with ovens , which relieved the Jews of maintaining the fire during the Shabbat. (12)

In the city as in the country, Moroccan Jews lived in perfect harmony with their fellow citizens in a bi-communal environment that was shaped in a generally serene and peaceful manner for more than a millennium. (13) And like any minority in human society, it happened that the weakest among them suffered the excesses of a wicked minority and benefited in return from the protective benefits of the majority. Collective and generalized exactions against Jews because of their faith rarely happened at the hands of religious zealots. In normal social relations, their total integration into Moroccan culture made them a stable component of it.

Community life in this bi-communal space had its charm and richness. It maintained in an implicit and spontaneous way a touch of humanism in the Moroccan cultural environment through the natural acceptance of diversity, expression of feeling affection towards the other, in spite of his difference, and the leniency towards the human being as such. These values were fullexpressed in the festivities through the exchange of cakes, meals, and recipes, through visits between neighbors, business partners or simple acquaintances, and through acts of support or compassion for one another in the context of a friendship in “otherness”. These transcendent human values were cultivated in diversity and were best expressed in the serenity of mutual recognition. (14)

All this beauty of living together was lost with the departure of our Jewish compatriots. The divorce was sealed with the Six-Day War in 1967. (15) The expulsion of the Palestinians from their land and the denominational exclusivity established by Zionism in occupied Palestine altered in Morocco, in an amalgam between Zionism and Judaism, a perception of the Jew built around ancestral values of cohabitation and conviviality.

This time-old coexistence and conviviality are explained by Robert Assaraf in the following terms: (16)

‘’Le Maroc et ses communautés juives constituent un véritable cas d’école. Aucune autre communauté juive n’a, en effet, conservé un rapport aussi fort et aussi fructueux avec sa terre d’origine, un rapport d’autant plus intense qu’il ne recèle rien de conflictuel. Cette conception apaisée et sereine du passé, fondée sur le souvenir de la multiséculaire coexistence mutuelle entre musulmans et juifs, vaut aussi pour le présent et pour l’avenir. Loin d’être une quelconque nostalgie, l’identité marocaine est une certaine conception du monde.’’

[“Morocco and its Jewish communities are a real textbook case. No other Jewish community has maintained such a strong and fruitful relationship with its land of origin, a relationship that is all the more intense because it is free of conflict. This calm and serene conception of the past, based on the memory of the centuries-old mutual coexistence between Muslims and Jews, is also valid for the present and for the future. Far from being a nostalgia, the Moroccan identity is a certain conception of the world.”]

Moroccan Jewry has suffered a massive reduction in numbers since Morocco’s independence, from 300,000 individuals to 3,000 today. Yet the Moroccan-Jewish identity is still alive, through the thousands of Moroccan Jews present in Israel, France, Spain, Great Britain, Canada, the United States, and Latin America, where they have recreated specific institutions while successfully integrating into the surrounding society.

In this regard, Mehdi Boudra writes in Atlantic Council: (17)

‘’Morocco has been a vibrant center of Jewish life for millennia—a history that the country still honors in its daily relationships and embrace of different religions and ways of life. Before the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, the Jewish population in Morocco reached almost three hundred thousand people. It was the biggest non-Ashkenazi community in the world and the largest Jewish community in the Muslim world.

Today, the Jewish community living in Morocco does not exceed three thousand members. However, the Moroccan Jewish community remains the largest in the Arab world. For example, in the coastal city of Casablanca, there are twenty active synagogues, seven kosher restaurants, five kosher butchers, and four Jewish schools.

Since 1997, the Foundation of Moroccan Jewish Heritage has preserved dozens of synagogues around Morocco and, in 1997, created the only Jewish museum in the Arab world, in Casablanca. With the full support of the Moroccan Monarchy, local Jewish communities have preserved more than 167 Jewish cemeteries and shrines throughout the Kingdom.

In 2020, in the port city of Essaouira, King Mohammed VI inaugurated Bayt Dakira (The House of Memory), a center dedicated to the historic Convivencia between Jews and Muslims in Morocco. Furthermore, to support the preservation of Moroccan Jewish cultural heritage, the king launched a conservation plan for the former Jewish quarters of several cities. This plan has included the rehabilitation and renovation of Jewish sites, as well as the restoration of Jewish names to the streets of the quarters.’’

Religious celebrations

Shabbat is a Jewish holiday celebrated on the seventh day of the week according to the Hebrew calendar, i.e. Saturday. The Jews, just as God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh, must not only rest but also avoid all productive activities (turning on the light, driving, cooking, etc.).

The Shabbat begins on Friday evening at sunset and ends on Saturday night when the third star appears in the sky. All preparations for this celebration must be done the day before, including cooking:

“Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, 10 but the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your male or female servant, nor your animals, nor any foreigner residing in your towns. 11 For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day. Therefore, the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.’’ (Exodus 20:8-11). (18)

It is interesting to note that both Islam and Judaism have established a weekly rest period: Friday for Muslims and the Sabbath on Saturday for Jews. One can also compare these days of rest with the other Abrahamic religion, Christianity, which establishes Sunday as a day of rest.

Friday (Jumuca) is a very important day for Muslims. The root of the word Jumuca means “to gather”. It was probably the first followers of Islam in Medina who, like the Jews and Christians, chose a particular day to celebrate the prayer together. All Muslims in the world are invited to gather at the mosque every Friday to perform the noon prayer together. Just before the prayer, they listen to the traditional sermon of the imam in which he develops many religious principles while offering them various advice. In Islam, Friday is considered a blessed day.

‘’O you who believe! When you hear the call to prayer on Friday hurry to call upon God and forsake all business transactions. That is far better for you, if you only knew!’’ (Qur’an, 62:9).

يَٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوٓا۟ إِذَا نُودِىَ لِلصَّلَوٰةِ مِن يَوْمِ ٱلْجُمُعَةِ فَٱسْعَوْا۟ إِلَىٰ ذِكْرِ ٱللَّهِ وَذَرُوا۟ ٱلْبَيْعَ ذَٰلِكُمْ خَيْرٌ لَّكُمْ إِن كُنتُمْ تَعْلَمُونَ

Thus, in the Mellah, the Jewish women prepare on Friday evening, the night before Shabbat, dishes such as dafina دفينة . (19 These dishes were then taken to the Muslim baker, who had an oven and could therefore heat the dishes until Saturday noon. Indeed, it is prescribed to eat a hot meat dish on Saturday noon, and the dafina has to cook for 15 hours according to tradition. (20) This was only possible with the Muslim baker’s oven. (21)

It is interesting to note that during the Shabbat, in the Mellah, all the shops, whether belonging to Jews or Muslims, are closed. In addition, markets are generally not held on Saturdays.

In the same spirit, during the daily breaking of the fast called the ftourفطور, at sunset during the month of Ramadan,it was common for Jews to distribute food to their Muslim friends and neighbors in need so that they could celebrate the holy month of Ramadan with dignity. This solidarity still exists today: some Jewish associations continue to distribute meals to Muslim families at the time of the breaking of the fast. These meals are typical culinary products of the month of Ramadan, such as dates, tea, lentils, and chickpeas.

The last day of the week of the Jewish Passover is marked by the ritual of breaking of the dietary prohibitions, often called (22) Mimounaميمونة among the Jews of the Maghreb. On this occasion, a festive dinner is organized. The fellahs (Arab and Amazigh peasants) from the surroundings come to sell the products which the Jews need for the celebration. Muslims are also invited to take part in the holiday. In the past, Jews also went out for family walks in the countryside and picnicked on the land or in the orchards of their Muslim friends. Such a visit was seen by the latter as part of a rite that brought good luck and good harvests since the word Mimouna/Mimoun means good luck in Moroccan Arabic . Thus, the Mimouna was the flagship inter-religious and inter-community event, a celebration of Jewish-Muslim cohabitation in Morocco. (23)

The Muslim-Jewish commonality is explained by the Moroccan social scientist Simon Lévy (24) in the following terms:

‘’D’une façon générale, le judaïsme marocain est concerné de deux manières. Il porte d’abord dans sa conscience le témoignage d’une heureuse cohabitation au Maroc avec l’Islam et l’Arabité et le souvenir de l’attitude courageuse et historique du Roi Mohamed V qui avait protégé les juifs marocains contre les décrets racistes de Vichy. D’autre part, les conflits récurrents entre Israël et les pays arabes ont occasionné des vagues d’émigration de juifs marocains soumettant la communauté juive à une certaine tension, mettant parfois à mal l’harmonie de sa coexistence paisible dans la société marocaine. En fait, les périodes d’émigration ont été vécues dans le déchirement et la frustration à la fois par la communauté juive et par la communauté musulmane du Maroc. C’était une phase difficile et même si elle n’a comporté ni menace, ni contrainte pour les juifs, elle s’est traduite, surtout après 1967, par un repli de la communauté israélite sur la vie quotidienne et dans une sorte de marginalité — paisible, certes — par rapport à la vie publique.’’

[‘’Generally speaking, Moroccan Judaism is concerned in two ways. First, it bears in its conscience the testimony of a happy cohabitation in Morocco with Islam and Arabism and the memory of the courageous and historic attitude of King Mohamed V who had protected Moroccan Jews against the racist decrees of Vichy. On the other hand, the recurrent conflicts between Israel and the Arab countries have caused waves of emigration of Moroccan Jews, subjecting the Jewish community to a certain amount of tension, sometimes undermining the harmony of its coexistence in Moroccan society. In fact, the periods of emigration have been experienced in heartbreak and frustration for both the Jewish and Muslim communities in Morocco. It was a difficult phase and even if it did not threat or constraint for the Jews, it resulted, especially after 1967, by a retreat of the Jewish community into everyday life and in a kind of marginality – peaceful, certainly – in relation to public life.’’]

Terminological similarities

The first chapter of the Qur’an begins with a praise al-Hamdu Li-Llâhi ‘’praise to God’’ الحمد لله just like all the blessings of rabbinic Judaism barukh attah adonai בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ, מֶלֶך הָעוֹלָם“praise you God”. (25) Further on, God is called the “Lord of the Peoples”, which is a semantic and conceptual reminder of the main Jewish blessing (“king of the universe:” Melech Ha’Olam (26) (27) You’re the king of the universe אתה מלך היקום.”אתה רק רוצה “יום קלי רובינסון).

Another expression present in the daily prayer of Muslims is: Allahu akbar “God is great” اللهأكبر which is a call to magnify God. This notion has an immediate semantic equivalent with the Hebrew Gaddel גָּדַל ‘’to magnify’’ (28) made familiar by the numerous praises that appear in the kaddish (29) recited during the obligatory prayers.

In the Maghreb, the Arabic language has affected the Hebrew religious terminology. (30) The Jews of the Muslim world adopted the Arabic language and Arabic terminology was often used for Jewish realities even when a Hebrew term existed. (31) The Torah could thus be referred to by the Arabic terms ash-Sharîca (the law) الشريعة or al-Kitâb (the book) الكتاب. The chapters of the Torah were sometimes even referred to by the name given to the chapters of the Qur’an (sûra) السورة . The officiant could also be called imam. (32)

Fasting is a common requirement in Judaismֹ ṣôm צוֹם, and Islam sawm صوم. In both religions, it is a form of penitence that helps one become more aware of the fate of the underprivileged. This ritual obligation is stipulated in both sacred texts, Torah and Koran. Fasting requires the deprivation of food and abstention from sexual relations and other sensual pleasures.

Islam and Judaism set the prohibition according to the calendar. For example, the Qur’ân requires fasting from dawn to dusk during the month of Ramadan. The Torah imposes a fast from dusk to dawn on the tenth day of the seventh month according to the Hebrew calendar. This is called the fast of Kippur. (33)

Food, and its conviviality lasting effect

The migratory phenomena lead one to evoke the processes of acculturation and integration, as well as to work on the concepts of multiculturalism, and interculturality and to demonstrate in which term a kitchen is a place of exchanges and transmission. Imbued with its Moroccan origins and strongly attached to the values of Judaism, Moroccan Jewish cuisine is a model of fusion between two communities, not to say two religions. (34)

For centuries, Jews have been present in Morocco and religious gatherings, whether Muslim or Jewish, were between these two communities, where each was proud to share their gastronomic know-how with the other.

It is important to discuss cultural and religious symbols in order to study the similarities in Moroccan Jewish-Muslim culinary art through the coexistence of Jews and Muslims in Morocco for centuries.

Food and cooking represent a specific area of intercommunity exchange. As such, it is important to note the similarities in culinary terminology. For example, the stuffed meat (beef/veal, lamb/sheep, pigeon, chicken…) is called pastilla, b’stilla, bestel in both Jewish and Muslim cuisines. In Morocco, this dish has been introduced in the most festive menus of the respective religious calendars. (35)

More often than not, Jews and Muslims exchanged recipes and some ingredients when shopping at the market. Women played an important role in these exchanges: they were the ones who prepared the menus, sometimes together, in the inner courtyards of some houses with several families. Jewish and Muslim women could also meet to prepare certain foods.

Jewish and Muslim kitchens in Morocco use many of the same ingredients such as spices and herbs such as cumin, coriander, saffron, red pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, parsley, or mint … Olive oil and peanut oil are widely used in both cuisines, as well as honey in pastries.

Two shared vegetables that appear in the Maghrebi kitchens without distinction of religion are cardoon and chard. Cardoon is used in stews in the traditional Shabbat dish: t’fina or dafina, (36) cooked for several hours from Friday to Saturday.

The culinary invention of North Africa, the couscous carrying luck or good fortune (baraka) بركة . In Muslim communities, it is at the heart of almost all major holidays of the Muslim religious calendar. It is also found on the tables of Jewish festivities: it is a dish frequently served on Friday night dinners to open the Shabbat.

The concept of social justice (tzedakah , zakât)

The concept of social justice, tzedakah צדקה in Hebrew, and zakat زكاة in Arabic occupy an essential place in Jewish and Muslim life, between purely free giving and concern for social redistribution. The Jewish notion of tzedakah finds its source in biblical teachings. (37)

In concrete terms, the Bible designates the poor, the widow, the orphan, and the foreigner as beneficiaries of social justice. The Bible also shows great concern for the solicitude towards the wage earner of any condition. The Talmud’s discourse on tzedakah lends redemptive powers to it. In addition, great attention is paid to the ethical question of how to dispense social justice while preserving the dignity of the recipient.

The Islamic notion of charity is present in the Qur’ânic teachings. The Qur’ân encourages Muslims to do good works, including zakât, which also means redemption and purification. Zakât is to be applied to those in need such as the poor, the travelers, the indebted, the captives, and the orphans.

In Islam as in Judaism, the notion of redemption is therefore strongly associated with zakât. For example, in the Middle Ages, men practiced zakât when they were ill, in the hope of being healed. In Arabic, there is an expression that translates as “He was healed by zakât.’’ In Hebrew, the equivalent is: “tzedakah saves from death (38) צדקה תציל ממות כפשוטו.”

In both religions, the gift made in secret is considered a moral act of great moral value, and great merit is associated with giving to loved ones, and to one’s neighbors.

Ritual slaughter among Jews and Muslims

This practice, called shehita שְׁחִיטָה, consists in cutting the throat of the animal in order to make it pure and fit for consumption while inflicting as little suffering as possible, in order to make it kosher. (39) The act itself must be performed by a shohet שוחט, a ritual slaughterer. The shohet must be highly trained. Before the killing, he must recite the blessing for the slaughter. The incision must be very precise it is done with a special knife called halef. (40) This knife is made of steel and is equal to twice the width of the animal’s neck so that the incision is made without interruption to reduce the animal’s suffering as much as possible. Thereafter, the bleeding must be complete and certain fatty parts are considered unfit for consumption according to Jewish belief. The killing of the animal must be perfectly executed to be kosher. An incorrectly slaughtered is called nevela נְבֵלָה (the equivalent of “carrion” in English) or treifa טְרֵפָה (equivalent to “torn”).

Kosher means “valid, conforming” and halâl حلال means “licit, legitimate”. The meaning is therefore close. In their common meaning, they refer to the status of foods permitted to Jews and Muslims respectively. The Torah forbids the consumption of mammals that do not ruminate and that do not have a split hoof, reptiles, seafood, insects, fish without scales or fins, or birds of prey. It also prohibits meat and milk, blood, and certain fats. The Torah strictly regulates slaughter and requires the verification of all internal organs.

The rules of halâl حلال are defined in the Qur’ân. The Qur’ân explicitly prohibits pork, blood, and un-slaughtered animals. (41) The Qur’ân also requires man to abstain from alcohol, although it does not explicitly forbid it. The Qur’ân requires the name of God to be spoken at the time of slaughter.

The Islamic Sharî ca allows the Muslim to eat the meat of slaughtered animals undertaken by a shohet but disallows any meat of Christian origin.

The practice of circumcision

For both religions, the practice of circumcision finds its source in the history of Abraham. (42)

In Judaism, in accordance with the act practised by the patriarch on his son Isaac, eight days after his birth, the Jewish boy must be circumcised as a sign of a perpetual covenant between God and his people. The act of cutting the foreskin of the new-born takes place during a ceremony where ten adult men are present. The operation is performed by a mohel מוֹהֵל, a person specialized in the realization of this rite. According to tradition, circumcision removes a part of the man so that he experiences the lack.

For people of Jewish faith, male circumcision is mandatory as it is prescribed in the Torah. In the Book of Genesis, it is described as a mark of the covenant of the pieces between Yahweh and the descendants of Abraham: (43)

‘’And God said unto Abraham: ‘And as for thee, thou shalt keep My covenant, thou, and thy seed after thee throughout their generations. This is My covenant, which ye shall keep, between Me and you and thy seed after thee: every male among you shall be circumcised. And ye shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin; and it shall be a token of a covenant betwixt Me and you. And he that is eight days old shall be circumcised among you, every male throughout your generations, he that is born in the house, or bought with money of any foreigner, that is not of thy seed. He that is born in thy house, and he that is bought with thy money, must needs be circumcised; and My covenant shall be in your flesh for an everlasting covenant. And the uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin, that soul shall be cut off from his people; he hath broken My covenant.’’

Among Muslims, the first son of Abraham, Ismael, an ancestor of the Muslims, was circumcised on the same day as his father. He was 13 years old, the age at which Muslim boys should be circumcised. However, in practice, they are often circumcised much younger. Although there is no Qur’ânic text prescribing it, it is strongly recommended and systematically practised.

Transmission of religion

According to Hebrew law (halakha הלכה ‘’way’’), (44) membership in the Jewish people is due to matrilineal descent, which means that it is the mother who determines whether or not the child is Jewish. Judaism conforms to the concept of Mater semper certa est, i.e. the idea that one is always absolutely certain of the identity of the mother of a child, but one is more difficult to be sure of the identity of the father. (45)

Therefore, a child born to a Jewish mother and a non-Jewish father is Jewish, while a child born to a non-Jewish mother is not. How can it be considered that religion is actually transmitted through the mother? What about the influence of the father? In many societies, the social identity of the child is primarily determined by the identity of the father (e.g. transmission of the family name).

However, Judaism considers that there is an “identity of being beyond the simple “social identity“’’. The “being” would only become complete after the pregnancy of the woman. It is therefore intrinsically linked to the mother who has allowed life to come to fruition.

It is worth noting that some liberal, Reform, and Reconstructionist Jewish movements in Europe, and the United States, not out of denial of the rules of the Torah, but out of a desire to adapt to the modern age. They have decided and considered, since the 1980s, that the transmission by the father is worth the transmission by the mother of children of a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother. However, they recommend the conversion of the non-Jewish mother to Judaism.

On the other hand, there are as many ways to define oneself as a Jew as there are Jews. There are Orthodox Jews, believers, secularists, agnostics, and atheists. Each one lives his Judaism in his own way.

Among Muslims, the tradition is that Islam is transmitted through the father, hence the fact that there is no problem for a Muslim to marry a non-Muslim woman since the children will be educated according to the religion of the father. On the other hand, the marriage of a Muslim woman to a non-Muslim man is seen as problematic, even forbidden, unless he converts to Islam. The Qur’ân sheds little light on this subject, as it was not of great concern at the time when it was transcribed.

Jewelry

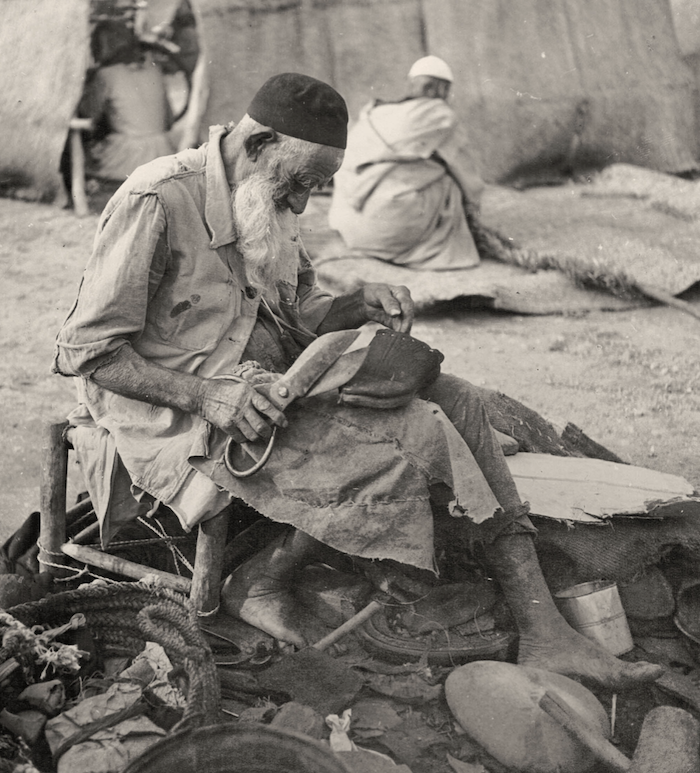

The jewels were worn by Jewish women, but also by Amazigh/Berber women. They reflect the importance of Jewish jewelry artisans, who were almost the only ones to make jewelry in Morocco until the XXth century. Their production was aimed at both Jewish, and Muslim women.

The jewels of the Jewish women of the mellahs were largely similar to those of the Amazigh/Berber women. It was common to wear several necklaces made of large hollow balls. Voluminous bracelets were common: often hinged, they were decorated with green or yellow enamel. Women wore very large rings as earrings. (47)

Jewish and Amazigh/Berber women also shared the wearing of the mahdour, a head ornament of 15 to 20 centimeters high mounted on a frame of rigid fabrics, with straps of fixing. The whole thing is held together by silver bars.

In the North of the Atlas, Muslims were not allowed to work with gold and silver, because of this prohibition, until the middle of the XXth century, the jewelers in the cities were practically all Jewish. The Jewish artisans worked in the mellah, (48) and Muslims went directly to them to make their purchases and order special jewels.

In the more remote rural or mountainous areas, Jewish villages often had one or more jewellery artisans. In this case, they would go to the weekly suks (market) themselves, with a case of jewellery, in order to resell their production.

Accessories were not reserved exclusively for women. Men also wear headgear, which allows for determining their religious affiliation. Thus, Jews wear the (49) kippah כיפה and Muslims wear the white sheshiya.

The Wedding

The Jewish wedding is celebrated in the presence of two witnesses and conducted by a rabbi. The bride and groom are reunited under a bridal canopy, the houppa חוּפָּה, symbolizing the new home of the couple. The marriage is sealed by the reading of the ketubah כְּתוּבָּה, the marriage contract, a legal document written in Aramaic, signed by both parties before witnesses, and given to the bride. The ceremony concludes with the breaking of a glass, a symbolic gesture performed by the groom in memory of the destruction of the Temple. (50)

In the case of Muslim marriage, a contract is concluded in front of two witnesses, in the presence of a judge, câdî قاضي, or legal authority, after recitation of verses of the Qurân, Sura IV 3 authorizes marriage with up to 4 wives, (51) provided that they are able to support themselves. Verse 20, of the same Sura also takes precautions for women, such as the ketubah. (52)

In the Maghreb, marriage is preceded by a ritual common to both traditions: laïlat al-henna ليلةالحنا, the night of the laying of henna. The celebration consists in blessing the union with a ritual intended to ensure abundance and fertility.

On the Moroccan Jewish Henna night, Danny Azoulay writes: (53)

‘’When talking about a Jewish henna/ hina, it is a vision of the Moroccan Jewish henna party that immediately comes to mind: brightly colored garments, Fez hats, tables of marzipan candies, dates and special pastries, authentic Moroccan music blasting while family and friends dance with infectious enthusiasm. And, of course, a fair amount of “lululululu”.

The bride and groom dress in lavish kaftans and jellabiyas, according to Moroccan wedding traditions, and very often have several costume changes through the evening. They are the king and queen for the day and are often carried into the hall on elaborately decorated ottomans and seated on thronelike chairs. Guests are encouraged to change into the brightly-colored traditional clothes provided by the host. Gifts (usually gold jewelry) are given to the bride and groom by the families.

Finally, the mud-like henna paste is generously applied by the bride’s mother or grandmother: in a circular shape, on the palms of the bride and groom. Afterward, the palms of the hands of all the guests will be hennaed one by one- and they, too, will be blessed with good luck. Henna is said to protect the couple from the evil eye and to bless them with luck, health, and fertility. In Morocco, the Jewish henna party would have taken place on the days preceding the wedding and may have gone on for several days. But, today, in Israel, the henna party will take place a week or even two, beforehand. There are those who incorporate the ceremony into the wedding, itself.’’

Carrying the bride and groom on a chair is also a ritual common to both Jewish and Muslim weddings in Morocco. This practice has its origin in ancient Egypt. Indeed, Egyptian traditions reached the Maghreb long before the arrival of the Arabs, through trade and commerce but especially through migration. The Jewish populations settled in Morocco before the arrival of Islam, those who had fled from Egypt have brought this tradition. Among the Muslims of Morocco, this practice is called al-camariyya العمارية.

Morocco, a holy land for the Jews

The Jews never completely left Morocco. They were not driven out, even though they left en masse and the country was emptied of Jews like the rest of the Arab world. In spite of this, the door has always remained open.

There were always Muslim families who took care of the maintenance of the places of worship and the Jewish sanctuaries. It is a difficult status to identify. They were always called “the guardians“. At that time, Jewish rabbis and beadles lived there, these Muslims assisted them. When they left, the Jews entrusted them with the keys to the sanctuaries and the memory that goes with it.

The guardians are very humble Muslims, very much penetrated by the sacredness of the task of guarding the tombs of a religion that is not their own. They are the guardians of the memory.

There was no collective return, but there are individual returns. There is a kind of small trend among people: they say they want to go and grow old and die in Morocco. It’s very symbolic. Because the link remained and the departure was accompanied by a lot of nostalgia. (54)

On the nostalgia of Moroccan Jews, Emanuela Trevisan Semi writes: (55)

‘’In Israeli public space feelings of nostalgia towards Morocco have found various forms of expression, starting as early as 1986, when a statue was unveiled to Mohammad V in Ashkelon, a city with a significant Jewish-Moroccan presence. However, it was in the year 2000 that Israeli public life began to set up places of remembrance connected with Morocco. André Levy has written that it is as if the Jews had never left Morocco, at least as far as the unbreakable bonds binding them to the king of Morocco are concerned. The Moroccan flag flies next to the Israeli flag in the pamphlets published by the National Committee for the Memory of Hassan II, a body formed three days after the king’s death (on 23rd July, 1999) and whose office is in Jerusalem. The committee has set up an association whose aim is to further the memory of the king of Morocco in Israel by giving the name of Hassan II to seventy Israeli public places such as squares, roads, shopping centres, parks and gardens. The museum of the Jews of Morocco (Centre mondial du Judaïsme d’Afrique du Nord- David Amar) located in the middle of an Oriental/Andalusian garden (in the ancient Moghrabi quarter of Jerusalem) is in strict Morocco style. The “Moroccanisation” of Israeli public life continues with the re-establishment of the worship of those saints already celebrated in Morocco by Jews and Muslims together. Netivot, the place of residence of the charismatic leader Baba Sali, has become a new centre of Moroccan religiosity while Baba Sali’s son has had a sanctuary built in memory of his father’s death in Moorish style. Netivot has then became one of the country’s principal religious centres, a place where genealogies of Moroccan saints have been revived.’’

Many people look at this common history with both tenderness and sadness, as if the exodus of the Jews had collectively amputated a part of their identity. It sometimes seems more difficult to deal with the bright side of this past. (56)

Simone Bitton, director of the documentary ”Ziyara” (57) on Jewish memory in Morocco, in an interview with Soulayma Mardam Bey for L’Orient-Le Jour admits:

”En tant que juifs arabes, notre grand traumatisme vient du fait de sentir que notre identité est en train de disparaître. Je ne souhaite cela à personne. Je fais partie des dernières personnes au monde à se définir ainsi parce que je porte en moi ces deux identités. Des gens comme moi, il n’y en aura bientôt plus, et ce, non pas pour des raisons idéologiques, mais tout simplement parce qu’il n’y a plus de juifs dans le monde arabe. Nous ne disparaissons pas par le massacre, mais par l’histoire, ce qui ne veut pas dire que nous n’en avons pas. Les gens dans mon film répètent que le judaïsme fait partie de leur identité en tant que musulmans marocains. C’est une chose qu’ils ressentent très profondément. Et moi je peux dire que l’islam fait partie de mon identité de juive marocaine. Le judaïsme fait partie de l’identité arabe et c’est une chose dont les Arabes d’aujourd’hui devraient d’ailleurs prendre conscience. Cela leur ferait du bien.”

[”As Arab Jews, our great trauma comes from feeling that our identity is disappearing. I don’t wish this on anyone. I am one of the last people in the world to define myself as such because I carry both identities within me. There will soon be no more people like me, not for ideological reasons, but simply because there are no more Jews in the Arab world. We are not disappearing by massacre, but by history, which does not mean that we do not have any. The people in my film repeat that Judaism is part of their identity as Moroccan Muslims. This is something they feel very deeply. And I can say that Islam is part of my identity as a Moroccan Jew. Judaism is part of the Arab identity and this is something that Arabs today should realize. It would be good for them.”]

The Jews of southern Morocco: Jewish-Amazigh intimacy

The Jews began to immigrate to Morocco and settle in the valleys of the south as early as the VIth century BC but also at the beginning of the Christian era. Historical documents attest to the existence of many Jewish communities in the valleys of Draa, in the Sous at Wijjan, Assaka of the Anti-Atlas in Illigh, Ifrane, and in Oued Noun on the Saharan border since the middle age. (58)

Traditions report that prophets persecuted by Nebuchadnezzar would have fled by the sea to disembark to Massa from where they would have left towards the east inland. Sidi Chanaouel, would have passed by Tamdoult n-Ouaqqa (Bani) where he would be buried at the foot of the mountain. Sidi Daniel would have arrived at Taguemmout (central Anti-Atlas central) (59) where he would be buried. Sidi Ouarkennas would be buried between Tizerht and Issafen.

The Jews were generally bilingual, Arabic and Berber speakers. Some of them were exclusively Berber-speaking. It is in that the Jews seem to have ensured a notable part of the economic activity. Their communities were born and developed in the most commercially active regions. The growth of these communities in these regions appears to be almost parallel to that of the trans-Saharan caravan trade. (60) It is probably the consequence of one of the important laws of Islam, which expressly forbade usury (ribâ الربا).

The non-Muslims, in this case, Jews, became the official pawnbrokers, in an Islamic state that guaranteed the protection of Jewish communities, as well as their right to practice their religion. However, in most of these areas, particularly in the sub and on the margins of the Sahara, the control of the central government was very lax, if not entirely absent.

Illigh was destroyed by the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Rashid (1631-1672) in 1670, but recovered its political position at the end of the XVIIIth century under Sidi Hashem ben Ali Illighi (died in 1825). Possessing great wealth and great power, he had under his orders fifteen thousand horsemen of the best armed. All the caravans coming from western Sudan find it necessary to ensure his friendship and protection. Thus, the Semlalites “of Illigh” were able to monopolize the trade of the south around the annual moussem (61) of Sidi Hmad u Musa, which allows one to suggest a close correlation between trade and power in the history of Morocco. The travelers gradually abandoned the Draa and Tafilalt, to the benefit of Souss and Oued noun, practising trade with the Europeans (Dutch, English and other nations).

Sources show that the community of the Zaouïa of Sidi Hmad u Musa, as well as the neighboring communities were closely linked to the leader of the powerful Illigh family who entrusted their Jews with everything flowing towards Sudan and Essouira especially after 1765, various products (ostrich feathers, gum, ivory, etc.) and the purchase of imported items (sold on the occasion of moussems) as well as financial transactions of usurious nature, which operations were sometimes recorded in deeds written in Hebrew characters. The Jews of Illigh were considered as protected from the zaouia. If they were robbed or killed, the Sharif punished in retaliation the locality to which the criminals belonged. Recent studies on Illigh and on its Jews show that the social ties between them and the inhabitants were very narrow, they seem to have ensured a significant part of economic activity.

The Jews of southern Morocco faced with the upheavals of the XVIIth to the XIXth centuries and despite the impassable gap of religion and residential segregation, daily relations of tolerant good neighborliness do not exclude eruptions of savage violence in times of crisis. All this in the context of an essentially rural country, fiercely isolated and withdrawn , suspicious of anything that comes from outside non-Muslims.

The manuscripts available attest to the relations between Muslims and Jews in Illigh, Ifran, Oued Noun and elsewhere in southern Morocco during this period of change, which coincided with the great upheavals of the XVIIth, XVIIIth and XIXth centuries and the eruption of the West and its civilization in a quasi-medieval society. (62)

The two communities remained faithful to their local, historical, and geographical environment. They were an integral part of the sociocultural, and linguistic landscape, living in a kind of identity difference, but they remained uncompromising about their faith and beliefs. One must note the absence of a hermetic barrier between the two communities, one can even speak sometimes of a total absence of any differentiation in the habitat. The deterioration of the inter-community climate has never reached during this period the stage of an open confrontation of a religious or ethnic nature, nor has it generally exceeded the limits of isolated incidents such as the case (which is not confirmed by any text ) of a certain Bouhlassn (the man with the stick) who attacked the Jews of Ifran around 1790, who pretended to be Moulay Yazid and tried to convert them by force before the head of the House of Illigh, their traditional protector in the region, could intervene.

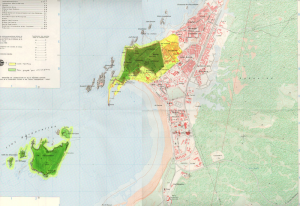

Essaouira, city of cultural commonality

The privileged position of Mogador has made it, during its long history, a place of accosting of merchant ships and conquering frigates. In the city of Mogador, the French were doctors, and civil servants. The Arabs ran the craft stores and the great merchant families were Jewish, heirs to the Tujjar as-Sultan تجارالسلطان, “the king’s merchants’’. They had flocked from all over Morocco in 1765 at the request of Sultan Mohammed III. The sultan had decided to establish in this city the great port of his kingdom and to make it the point of connection with the caravans coming from Africa. Thanks to a system of tax exemptions, a dozen trading houses were immediately established. In the middle of the XIXth century, Mogador had a large population of Jews living in the Mellah, the Jewish quarter located in the northern part of the old city. Later, those who could afford it moved to the beautiful mansions in the kasbah around Moulay Hicham Square. (63)

Essaouira was officially founded in 1765 by the Sultan Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah (1721-1790) later known as Mohammed III to provide the capital Marrakech with a new port and to weaken the Souss revolt by suffocating the port of Agadir (capital of the Souss region). This decision of geopolitical order also testifies to the will to make Essaouira the first new city planned in Morocco, a city populated by immigrants of all horizons and all confessions. Its founder had thus allocated a territory to each “ethnic group”: Chbanates, Ahl Agadir, Laalouj, Beni Antar, Bakher, and Tujjâr as-sultân (literally the Jew traders or merchants of the sultan).

The Jewish families that came to settle in Mogador were as follows: (64)

– Sumbal and Delvante from Safi ;

– Corcos and De la Mar from Marrakech;

– Aflalo and Pénia from Agadir;

– Lévy-Yuly, Lévy-Bensoussan, Anahory from Rabat;

– Aboudarham from the city of Tetouan.

The promising beginnings of the city’s economic development attracted other Jewish families from across the seas:

– De Lara, from Amsterdam;

– Akrich, from Livorno;

– Cohen-Solal and Boujnah, from Algeria.

Then came other families, from which came the “Sultan’s merchants”:

– the Cohen-Macnin, Sebag, Pinto, Belisha of Marrakech ;

– the Hadida and Israel, from Tetouan;

– the Méran of Safi and the Guedalla of Agadir.

The latter were for the most part Jews of Andalusian origin sheltered in the kasbah known as the “mellah“, while their other co-religionists (artisans, shopkeepers, peddlers) lived in the lower town. Although some authors trace the origin of a large number of Jewish families in the mellah of Essaouira to the Souss, including those of Rabbi Haïm Pinto and Rabbi Ed-Dery who lived in Agadir.

The Judeo-Berber etymology of Mogador (the name given to Essaouira by the Portuguese who came in the sixteenth century), according to Omar Lakhdar, asserts the presence of a Jewish community before the foundation of the new city by the Sultan.

From the outset, the Souiri mellah was distinguished by a very dense cultural and spiritual life. It developed its own identity based on a religious vocation. Spread out over two hectares, the mellah had at least sixteen synagogues and numerous cultural structures. Daily life was punctuated by the relatively “orthodox” religious practice in these mellahs, which included the exclusive presence of the Talmudic school, public mikvehs מִקְוֶה / מקווה (ritual baths) which welcomed great rabbis of international spiritual renown.

The whole city had up to 47 synagogues. This shows the importance of the religious dimension in the Jewish community of Essaouira, which was at one time more important in number than the Muslim community. When Essaouira’s port activities were at their peak, in the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries, the city had as many as 16,000 Jews among 22,000 to 25,000 inhabitants. Currently, there are four synagogues, maintained by private finance.

In his speech on April 14, 2013, King Mohammed VI reiterated his desire to preserve and enhance the Moroccan Jewish heritage: (65)

[“It is precisely this Hebrew particularity that constitutes today, as enshrined in the new Constitution of the Kingdom, one of the secular tributaries of the national identity, and that is why We call for the restoration of all Jewish temples in the various cities of the Kingdom, so that they are no longer just places of worship, but also a space for cultural dialogue and renewal of the founding values of Moroccan civilization.”]

‘’C’est précisément cette particularité hébraïque qui constitue aujourd’hui, ainsi que l’a consacré la nouvelle Constitution du Royaume, l’un des affluents séculaires de l’identité nationale, et c’est pourquoi Nous appelons à la restauration de tous les temples juifs dans les différentes villes du Royaume, de sorte qu’ils ne soient plus seulement des lieux de culte, mais également un espace de dialogue culturel et de renouveau des valeurs fondatrices de la civilisation marocaine.’’

A dynamic of coexistence and cooperation was created between the Jews, the Muslims, and the Christian community. However, the role of the Jewish merchants remained predominant. As soon as the first families of Jewish merchants were established, links were created between them. These were not only business relationships but also marriage alliances that strengthened the cohesion of these families.

From the middle of the XVIIIth century, the arrival of foreign merchants, mainly European, necessitated the establishment of consulates where Jews were employed as consuls, vice-consuls, and interpreters. With the mixing of cultures, the atmosphere in the city became cosmopolitan.

A genealogical study of the great Mogadorian families through time shows that they were all linked by marriage. This phenomenon creates closed clans and real dynasties. This can be seen in the genealogy of one of the first great tujjâr families of the sultan, the Guedalla, from Agadir, who were involved in international trade. They allied themselves with the Pintos, the Del Mar, the Aflalo, and, in England, with the Montefiores, the Sebag-Montefiores and even with the De Lara (who came to settle in Mogador towards the end of the XVIII century), and Cevi families from Amsterdam, who linked up with the Serfatys.

Jacob Guedalla (born around 1690) was the first to receive a building permit in the Casbah (Dar Parey) and the only Jew to be accepted in the Commercio. (66) Part of the family emigrated to Amsterdam in Holland and part to England.

The first consular agent who settled in Mogador in 1763 was the Danish consul. Salomon Corcos was appointed in 1823 as consular agent of Great Britain in Marrakech. In January 1862, Abraham Corcos was appointed vice-consul of America and the West Indies in Mogador. After his death in 1883, his son Meir succeeded him. Joseph Elmaleh and his son Reuben were vice-consuls of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Mogador.

A known phenomenon, which also existed in other societies, was the absence of marriages between members of different social classes. So much so that many members of the community, both men and women, remained single all their lives. The local poet Rabbi David Elkaim wrote a searing poem about this in which he expressed his indignation. (67)

After many decades of development and wealth, Mogador was in for a continuous decline as reported by Sideney S. Corcos: (68)

[”At the beginning of the 19th century several factors acted to the detriment of the economy: Europe imposed a blockade on exports because of frequent epidemics, the Napoleonic wars and the policy of Sultan Moulay Slimane (1792-1822), which slowed down trade with Europe. As a result, the commercial activity of Mogador dropped considerably, leading to other departures, either to Casablanca or Agadir, or across the Atlantic. For example, in 1800 and 1801 the merchants David Ben-Shabbat, Haïm Délavant and Shemuel Benadon arrived in London from Mogador. Some turned to other directions, such as the Azores and Canary Islands, including the Zafrani, Shabbat, Sebag, Attia, Ben Shimol, Ben Soussan, Amzaleg, Sabah, Azencot, Elmaleh families and even the grandson of the rabbi, the saintly Haïm Pinto, or finally to Gibraltar and Portugal (Benchabat and Chriqui families) in the middle of the nineteenth century.”]

”Au début du XIXe siècle plusieurs facteurs agissent au détriment de l’économie : l’Europe impose un blocus sur les exportations à cause des épidémies fréquentes, des guerres napoléoniennes et de la politique du sultan Moulay Slimane (1792-1822), qui freine le commerce vers l’Europe. En conséquence, l’activité commerciale de Mogador chute considérablement, poussant à d’autres départs, soit vers Casablanca ou Agadir, soit outre-Atlantique. Par exemple en 1800 et 1801 arrivent à Londres de Mogador les commerçants David Ben-Shabbat, Haïm Délavant et Shemuel Benadon. Certains se tournent vers d’autres directions, comme les îles Açores et les îles Canaries, dont les familles Zafrani, Shabbat, Sebag, Attia, Ben Shimol, Ben Soussan, Amzaleg, Sabah, Azencot, Elmaleh et même le petit-fils du rabbin, le saint Haïm Pinto, ou enfin vers Gibraltar, et le Portugal (familles Benchabat et Chriqui) au milieu du XIXe siècle.”

Sefrou, the ‘’Little Jerusalem of Morocco’’

From the XVth to the mid-XXth Sefrou had the highest concentration of Jews per square meter in any Moroccan city but it was also the city of Rabbis, saints, and Jewish learned men, a fact that earned it the nickname of the ‘’ ‘’Little Jerusalem of Morocco’’. (69)

But the city was not only a famed place of religious knowledge but also a financial platform that financed caravan trade to and from Timbuktu (in today’s Mali) and happily engaged in a form of unfair trade, by obviously, today’s standards, whereby merchants exchanged salt against gold, among many other things. (70)

In the suk of Sefrou, (71) Geertz and his team studied in great detail the bazaar economy of the city where the Jews prior to their arrival played a major economic role in the prosperity of the city. The analysis indicates several ethnological orientations, observes the obligations related to the transactions, the social identity, the merchants, the population frequenting the places, the uses established for each trade, and the suk as an economic place

There were, indeed, two types of Jews in the suk of Sefrou: the Sitting Jew يهوديدالجلاس and the Walking Jew يهودي د لمشي. The Sitting Jew was the equivalent of today’s banker. He held a tiny shop in the suk/bazaar and provided necessary funds for the trade caravans that left the city on and off to Timbuktu. The Sitting Jew was also the ‘’banker’’ who provided the necessary loans, on easy terms, to Berber farmers coming from the neighboring areas and Arab inhabitants of the city, in return for a fixed interest rate known as tâlec طالع meaning the ’’ascending’’. Given that usury الربا was strictly forbidden by Islamic sharica, for centuries Jews were the bankers of Morocco on internal and external levels. They arranged loans for the makhzenالمخزن(traditional government)as well as small and big traders and also individuals such as Berber peasants who paid back the money in the summer after the harvest.

In Sefrou, the Walking Jew was the trusted and able caravan guide who conducted this perilous enterprise to and back safely. He was known as (72) azettat ازطاط . He would lead the caravan through the territories of different tribes exhibiting their colors on entering their territory to ask for amânامان (peace and security) on payment of some sort of a tithe. Jews were the only accepted guides because they were trustworthy and diplomatic and had the flair to solve any problem that the caravan could encounter on it way.

The suk/bazar of Sefrou was not any given marketplace, it was a commercial place where loans were contracted, the caravan’s mission was negotiated, and gold was bought and exchanged for land or other goods. This market was the gate for trade with sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of Morocco and Jews played a major role in its success.

Having said that, the Jews of Sefrou were not only successful traders and played a key role in the development of the Moroccan economy but they were also key actors in social harmony and religious dialogue.

In Sefrou, Both Muslims and Jews shared in saint veneration. (73) In the northern quarter of the city, outside the walls there was the tomb of a female Jewish saint known as Setti Messcuda and somewhat related to another female Jewish saint, Setti Fadma, buried in the valley of Ourika, near Marrakesh. It seems, according to oral history, her shrine was destroyed around 1920 by the French to make a place for urban sprawl, however, there is no written document attesting to the veracity of this. According to oral literature, both Jews and Muslims visited her shrine for physical ailments and mental maladies.

Another important shared saint is situated in Jbal Bina, outside of the city, on the way to Fez. This is the famous Kâf al-Moumenكافالمومن ‘’The cave of the believer’’, the shrine of a saint venerated by both Muslims and Jews. According to oral history, this unknown saint is in both Jewish and Muslim hagiography and religious history.

All in all, like all the saints shared by both Muslims and Jews all over Morocco, Kâf al-Moumen is a stark example of religious communion, social Intimacy, and cultural conviviality.

The Jews of Sefrou were then and now very attached to their Moroccan identity and their Moroccanness, a strong feeling known as (74) Tamaghrabitتمغرابيت. On this particular point, Clifford Geertz writes: (75)

“from many points of view it looks exactly like the Muslim community; from as many others, totally different […] Moroccan to the core and Jewish to the same core, they were heritors of a tradition double and indivisible and in no way marginal.”

This point of view is shared by Daniel J. Schroeter who says: (76)

‘’Moroccan Jews have been the subject of numerous studies, most of which would agree with Geertz’s assessment. Yet what are the characteristics of this “Moroccan” Jewish core that so many scholars have assumed to be embedded in Moroccan society and culture? While scholars debate the similarities and differences between Muslim and Jews of Morocco and whether Muslim-Jewish relations were either relatively harmonious or fraught with tensions, very few question the essential Moroccanness of the Jews. Many contemporary Jews whose origins are from Morocco and who understand their Moroccanness as an identity deeply rooted in Moroccan soil share this general perception. Of all the Jews from the Islamic world, the tenacity of Moroccan Jews’ sense of attachment to their country of origins is perhaps unparalleled.’’

The Jews expelled after the Reconquista are well-received in Morocco

In the fifteenth century, Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal were welcomed by the Moroccan authorities, but these newcomers (megorashim), arrogating to themselves communal power in the south, were viewed with great suspicion by the native Jews (toshavim). (77) There is also a fear of their expertise and the economic competition that might result. The refugees havd their own synagogues, and cemeteries, and lived according to their own customs. Particularly in the north, in cities such as Tangier and Tetouan, (78) they assimilated local communities and turned these cities into hotbeds of Iberian Judaism, treating local Jews as forasteros (foreigners). Until recently, members of these communities spoke their own language, Haketiya, a form of Judeo-Spanish, while others spoke Judeo-Arabic. (79)

Later, Morocco served as a haven for many Marranos (Jewish converts to Christianity who secretly practiced Judaism: Crypto-Jews) (80) who arrived from the Iberian Peninsula and the surrounding islands. Jews practiced virtually all professions, including farming and ranching, but were mainly peddlers, artisans, small businessmen, and moneylenders.

Speaking of the influx of the megorashim to Morocco and how well they were received by the population and the authorities, Haim Zafrani writes: (81)

[“the number [of these Jewish emigrants] … is a matter of vague approximations, even imaginary and fantastical. However, one could retain, with the greatest caution, some of the figures collected in various documents: about forty thousand arrived in the ports of Arzila [present-day Asila], Salé, Badis and elsewhere on the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts, with about twenty thousand of them finding refuge in Fez or in the interior of the country. But we must take into account the number of emigrants leaving from the Spanish and Portuguese ports and of which little is known precisely, the hazards of the crossing, the number of victims at sea, (…) the populations that other plagues (popular riots, fires, famines and epidemics) have decimated, the families in transit continuing their journey to the East after a more or less long stay in Fez and in other metropolises. (…) We must add here (…) those among the Megorashim, landed on the peaceful beaches of southern Morocco, arrived in more welcoming places and established themselves there (Azemmour, Safi, old Essaouira, Agadir), or those who went deep into the country to the interior of the country to settle there, acquire land and integrate into the local economic and socio-cultural landscape (Marrakech and its region, the valleys of Todgha in the High Atlas).’’]

‘’Le nombre [de ces émigrés juifs] … relève de vagues approximations, voire de l’imaginaire et du fantasme. On pourrait cependant retenir, avec la plus grande prudence, quelques-uns des chiffres recueillis dans divers documents : une quarantaine de mille arrivés dans les ports d’Arzila [l’actuelle Asila], Salé, Badis et ailleurs sur les côtes méditerranéennes et atlantiques, une vingtaine de mille d’entre eux allant trouver refuge à Fès, ou à l’intérieur du pays. Mais il faut prendre en compte le nombre des émigrés en partance des ports espagnols et portugais et dont on sait peu de chose de façon précise, les aléas de la traversée, le nombre des victimes en mer, (…) les populations que d’autres fléaux (émeutes populaires, incendies, famines et épidémies) ont décimées, les familles en transit poursuivant leur voyage vers l’Orient après un séjour plus au moins long à Fès et dans d’autres métropoles. (…) Il faut ajouter ici (…) ceux qui parmi les Megorashim, ont débarqué sur les plages paisibles du Maroc méridional, sont arrivés dans des lieux plus accueillants et y ont fait souche (Azemmour, Safi, la vielle Essaouira, Agadir), ou ceux qui se sont enfoncés à l’intérieur du pays pour s’y établir, y acquérir des terres et s’intégrer dans le paysage économique et socioculturel local (Marrakech et sa région, les vallées de Todgha dans le Haut-Atlas).’’

Among the few testimonies about the settlement of expelled Jews in Morocco is that of Abraham Ben Salomon de Torrutiel, born in Spain in the province of Valencia in 1482. In his work Sefer ha-Kabbalah (‘’Book of Tradition’’), which dates from 1511, he writes that Abraham Ben David le Cordouan, after having described the tribulations on the way to North Africa and the misfortunes encountered at sea and in the cities of the coast at the hands of the Christian Spanish or Portuguese authorities, praises, on the other hand, the Sultan of Morocco, Muhammad ash-Shaykh al-Wattâsî (1472-1505) for his hospitable attitude towards the refugees, receiving them everywhere in his kingdom, especially in Fez, where he himself was established. This is what he says: (82)

“I will evoke the memory of the just king Moulay Mohammed, son of the great king Moulay AlChaykh, a just (hasid) among the just of the nations, who received the Jews expelled from Spain, who, until his death, behaved with kindness towards the people of Israel, for it was God [who] invested him with the sovereignty over the kingdom of Fez”.

This testimony reflects the sympathy that the Wattasid Sultans of Fez reserved for the Jewish exiles from Spain, after 1492, by welcoming them in the best conditions, despite some difficulties linked to the social and political unrest that marked this unstable period: lack of a central power over the entire Moroccan map, marked by years of violent struggles and violent wars between the Wattasids and the Saadians, drought, famines and cholera; elements illustrated particularly and perfectly by the testimony of Abraham Ben David le Cordouan.

Another testimony by Salomon Ibn Warga, (83) also expresses himself in the same terms concerning the welcome given to the Jews in question by the Moroccan sovereign.

According to Rabbi Abraham Azoulay, one of the members of the group that was shipwrecked upon arrival in Salé, the landing of the survivors was a miracle: (84)

” The people who arrived in Fez had no money and few clothes to cover themselves; they didn’t know where to stay. Sultan Muhammad ash-Shaykh al-Wattâsî welcomed them with compassion, seeking to alleviate their misery. The community of Fez organized itself to provide them with first aid “.

From these testimonies, we have been able to reconstruct some of the trajectories of the Jews expelled from Spain and who found refuge in Morocco, in very difficult conditions linked to the unstable context, socially, politically and economically in Morocco during the period 1492- 1497.

The Jews concerned arrived in successive waves and settled, temporarily or permanently, depending on the case, in the Mediterranean or Atlantic ports, under Portuguese control at the time, such as Tangier, Ceuta, Arsila, Safi, Azemmour, Mazagan; and in the metropolises of the interior of Morocco, under Moroccan -Muslim- control, such as Taza, Meknes, Debdou, Marrakesh, Sefrou and Fez.

In the east of Morocco, there was an important Jewish community, notably in Debdou, where Jews who had fled persecution in Spain at the end of the XIIIth century had taken refuge. After 1492, there was a massive arrival of several thousand Jews in the welcoming city of Debdou, so much so that it was the only Moroccan city, at the time, where the number of Jews greatly exceeded that of Muslims. (85)

Conclusion: vivre-ensemble

The cities of Sefrou, Essaouira, Debdou, Fez, Marrakesh, Tetouan, etc. with their millenary history, their civilizational wealth, and their soul full of spirituality, have always served as a true standard-bearer in its most universal scope, of the values of openness, peaceful coexistence and living together between Muslims, Jews and Christians.

This spirit of tolerance, peace, and communion that forms the DNA of these ancient cities, has earned them the originality to be “fortresses” of resistance and resilience to all “amnesia” and attempts to promote division, fracture and denial of others, offering, thus, through long centuries of history, the example of a peaceful Morocco, a singular space of freedom and humanism, where unity flourishes more in pluralism and diversity, making the Kingdom an unprecedented exception on a global scale.

Throughout the long existence of the Jewish minority in Morocco, the Jews thanks to their great sense of adaptability and dialogue have cultivated an intimacy with Muslims both Arabs and Amazigh/Berbers over the centuries and that is why they feel their departure to Israel, Europe, and the Americas as an open wound that would not heal, or as the French Moroccan politician and documentary-maker David Assouline, originally from Sefrou, said: ‘’a sweet wound’’. His documentary film on the departure of Moroccan Jews entitled: ’’Entre Paradis Perdu et Terre Promise’’ was introduced by the French daily newspaper Libération in the following terms: (87)

‘’Que reste-t-il de Sefrou, la petite Jérusalem du Maroc, paradis terrestre oriental adoré de Colette? Une mémoire, une douce blessure pour les enfants de ces milliers de juifs qui vécurent autrefois dans cette petite ville marocaine proche de Fès. «La terre d’Israel était ici» dit Moshe, un des derniers Juifs à avoir quitté Sefrou pour Israël. Ils sont partis les uns après les autres, chassés par l’indépendance marocaine, les guerres du Moyen Orient et cette peur diffuse qui a eu raison de la douceur de vivre ensemble, Juifs et Arabes, sans histoires. Il faut voir le docu de David Assouline pour les belles images de ce passé paisible dans la medina et découvrir, une fois de plus, que le drame de l’intégration ne se joue pas forcément là où on l’attend. Pour les anciens de Sefrou, la terre promise a eu un goût amer. «J’étais maître, je suis devenu serviteur», dit l’un d’eux qui raconte les humiliations, la morgue des juifs d’Europe et les jeunes filles qui tournent le dos quand on dit qu’on est Marocain. Pour finir par s’en accomoder, «Mes fils, au moins n’ont pas été traités de sales juifs».’’

[‘’What remains of Sefrou, the little Jerusalem of Morocco, the oriental earthly paradise adored by Colette? A memory, a sweet wound for the children of the thousands of Jews who once lived in this small Moroccan town near Fez. “The land of Israel was here” says Moshe, one of the last Jews to leave Sefrou for Israel. They left one after the other, driven out by Moroccan independence, the wars in the Middle East and the widespread fear that overcame the sweetness of living together, Jews and Arabs, without fuss. David Assouline’s documentary should be seen for the beautiful images of this peaceful past in the medina and to discover, once again, that the drama of integration is not necessarily played out where we expect it to be. For the elders of Sefrou, the promised land had a bitter taste. “I was a master, I became a servant”, says one of them who tells of the humiliations, the morgue of the European Jews and the young girls who turn their backs when they say they are Moroccan. In the end, he came to terms with the fact that “at least my sons were not called dirty Jews”.’’]

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

Endnotes:

- Campbell, C. L.; Palamara, P. F.; Dubrovsky, M.; Botigue, L. R.; Fellous, M.; Atzmon, G.; Oddoux, C.; Pearlman, A. & Hao, L. “North African Jewish and non-Jewish populations form distinctive, orthogonal clusters”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (34), 6 August 2012, pp. 13865–13870. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3427049/

- Taïeb, J. “Juifs du Maghreb”. Encyclopédie berbère, 26, 1 mai 2004, pp. 3952–3962. https://journals.openedition.org/encyclopedieberbere/949

- Andreeva, Sofia; Artem Fedorchuk, & Michael Nosonovsky. “Revisiting Epigraphic Evidence of the Oldest Synagogue in Morocco in Volubilis”, Arts 8, no. 4: 127, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040127

- Stillman N. A. The Jews of Arab land. A History and source book. Philadelphia: The jewish publication society of America, 1979.

- Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’Morocco: Encounter Of Amazigh And Jews And Their Germination Of Cultural Substratum – Analysis’’, Eurasia Review, October 7, 2019.https://www.eurasiareview.com/07102019-morocco-encounter-of-amazigh-and-jews-and-their-germination-of-cultural-substratum-analysis/

- Gerber, J. S. Jewish Society in Fez (1450-1700). Studies in Communal and Economic Life. Leiden: Brill, 1980, p. 24.

- Zafrani, Haim. Mille ans de vie juive au Maroc. Paris : Maisonneuve et Larose, 1983, p.15

- Gottreich, E. Jewish Morocco: A History from Pre-Islamic to Postcolonial Times. London: I.B. Tauris, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781838603601

- Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’The Judeo-Amazigh Cultural Substratum in Modern Morocco’’, Amazigh World News, February 19, 2021. https://amazighworldnews.com/the-judeo-amazigh-cultural-substratum-in-modern-morocco/

- Bennison, Amira K., & Maria Gallego. ‘’Jewish Trading in Fes on The Eve of the Almohad Conquest’’, Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Hebreo 56, 2007, pp. 33–51.

- Schroeter, Daniel J. ‘’The Shifiting Boundaries of Moroccan Jewish Identities’’, Jewish Social Studies, 15, 1, 2008, pp. 145-164. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236787398_The_Shifting_Boundaries_of_Moroccan_Jewish_Identities

- Schroeter, Daniel. ‘’Identity and nation: Jewish migrations and inter-community relations in the colonial Maghreb’’. In : La bienvenue et l’adieu | 1 : Migrants juifs et musulmans au Maghreb (XVe-XXe siècle), op. cit.

- Gottreich, Emily. “Rethinking the ‘Islamic City’ from the Perspective of Jewish Space.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, 2004, pp. 118–46. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4467697

- Ojeda-Mata, Maite. ‘’Jews under Islam in early modern Morocco in travel chronicles’’, Jewish Culture and History, 21:2, 2020, pp. 104-130.

- Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’The Departure of Moroccan Jews to Israel Bitterly Regretted’’, Jewish website, September 17, 2019, https://jewishwebsite.com/featured/the-departure-of-moroccan-jews-to-israel-bitterly-regretted/46551/

- Assaraf, Robert. Juifs du Maroc à travers le monde : émigration et identité retrouvée. Paris : Editions Suger Press, 2008, p 251.

- Boudra, El Mehdi. ‘’Morocco is building bridges to connect its youth with its Moroccan Jewish cultural heritage. Here’s how’’, Atlantic Council, December 2, 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/morocco-is-building-bridges-to-connect-its-youth-with-its-moroccan-jewish-cultural-heritage-heres-how/#:~:text=It%20was%20the%20biggest%20non,largest%20in%20the%20Arab%20world.

- Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2020%3A8-11&version=NIV

- Dafina (also skhina, tafina, tafna, matfun) is a traditional dish in the Jewish cuisine of Morocco. It is traditionally eaten during Seouda Shenit, the second Shabbat meal, which takes place on Saturday around noon. The word dafina comes from the Arabic ad-dafina, which means “covered”, “smothered”, relating to the method of cooking, which was historically done in a hole dug in the ground or in the earthen ovens of bakers.

- For religious reasons, Jews do not cook on Shabbat. However, since Shabbat is to be a time of “delight”, it is also prescribed to eat a hot meat dish. This problem is solved by cooking the dafina on Friday evening, before nightfall, and simmering it over a small fire (nowadays, a hot plate) for almost fifteen hours, which gives it a very special taste. At the end of the cooking time, the ingredients caramelize. The cholent (Ashkenazi dish) which appeared afterwards follows the same principle, but its taste is very different. Moroccan dafina is usually made of beef, potatoes, chickpeas, eggs and wheat. Sometimes rice is also included. There is also a dafina called Pessa’h (Jewish Passover) made of peas (without chickpeas, rice or wheat). At the table, salt, pepper and cumin are added. However, there are several local varieties, such as the dafina from Constantine, which is prepared with spinach.

- Amar, Rose. Cuisine juive marocaine. La cuisine de Rosa. Paris: Jean-Paul Gisserot, 2005.

- Though the practice only began to be recorded in the middle of the 18th century, its derivation and etymology are ancient. Possible derivations for the name Mimouna are: “Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef” (father of the Rambam Maimonides). Thus, the Mimouna might mark the date of his birth or death; the Hebrew word “emuna” (Hebrew: אמונה, meaning “faith”) or “ma’amin” (Hebrew: מאמין, meaning “I believe”); the Arabic word for “wealth” or “good luck” as on this day, according to midrash, the gold and jewelry of the drowned Egyptians washed up on the shore of the Red Sea and enriched the Israelites. Mimouna is associated with “faith” and “belief” in immediate prosperity, as seen in its customs of matchmaking, and well-wishes for successful childbearing; manna, which was the food God provided following the Exodus, and during the subsequent wandering in the desert. The name of a Berber goddess is also a possible etymology. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mimouna#:~:text=Mimouna%20(Hebrew%3A%20%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%9E%D7%95%D7%A0%D7%94%2C%20Arabic,Jews%20of%20Maghrebi%20heritage%20live.

- Levy, André. “Happy Mimouna: On a Mechanism for Marginalizing Moroccan Israelis.” Israel Studies, vol. 23, no. 2, 2018, pp. 1–24. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/israelstudies.23.2.01.

- Lévy, Simon. ‘’ Le judaïsme marocain, une référence pour la coexistence judéo-arabe’’, Confluences, 9, Winter 1994, pp. 131-138. https://iremmo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/0915.levy_.pdf

- בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ, מֶלֶך הָעוֹלָם… Transliteration: Barukh ata Adonai Eloheinu, melekh ha’olam… Translation: “Blessed are You, LORD our God, King of the universe…”

- Rabbi Katy Z. Allen. ‘’Melech Ha’Olam – King of the Universe’’, Ma’yan Tikvah’s Divrei Earth, October 24, 2015. https://mayantikvah.blogspot.com/2015/10/melech-haolam-king-of-universe.html

- https://context.reverso.net/translation/english-hebrew/king+of+the+universe Translation of “king of the universe” in Hebrew מלך היקום You’re the king of the universe. אתה מלך היקום.”אתה רק רוצה “יום קלי רובינסון And somewhere, on the road to their new life as a family, the Reverend Reece Wade stole away with his new son and dedicated him to the creator of life itself, the king of the universe. והיכנשהו, בדרך לחייהם, החדשים כמשפחה הכומר ריס וייד התגנב עם בנו החדש, והקדיש אותו לבורא העולם מלך היקום. “Shield us through this night of terror, O King of the Universe.”הגן עלינו בזו הלילה” “של טרור, מלך העולם

- Genesis 12:2 HEB: גָּד֔וֹל וַאֲבָ֣רֶכְךָ֔ וַאֲגַדְּלָ֖ה שְׁמֶ֑ךָ וֶהְיֵ֖ה NAS: And I will bless you, And make your name KJV: thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing: INT: A great will bless and make your name shall be