Tunisia Drifts Into Even More Dangerous Territory – Analysis

By ISS

By Peter Fabricius*

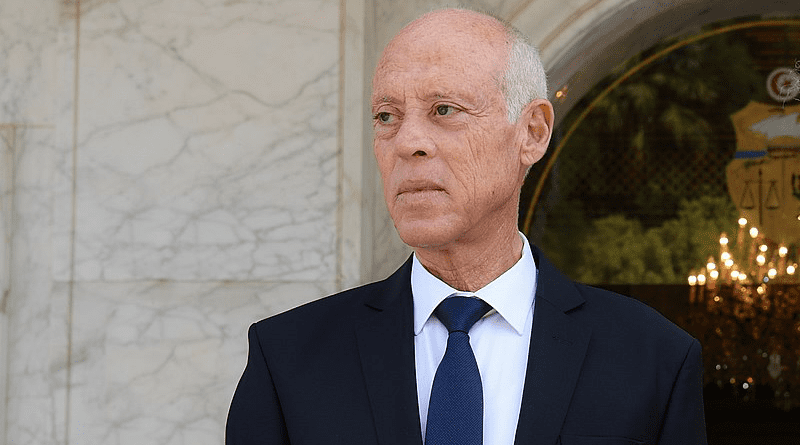

For a while, optimists could hope that President Kais Saied hadn’t abandoned Tunisia’s turbulent but exhilarating democratic project – even after he suspended Parliament and fired the prime minister last year, invoking a ‘state of exception’ that allowed him to rule by decree.

That hope now seems largely to have dissipated after Saied this month replaced the independent electoral commission with one he appointed entirely himself. The move appears designed to ensure the electoral body rubberstamps the outcome of a 25 July referendum on radical constitutional changes that will create some sort of grassroots democracy. The new constitution would come into effect after elections planned for December.

Saied’s scrapping of independent electoral observation sparked large public protests in the capital Tunis, with demonstrators chanting for democracy. Many also complained that ‘Saied has led the country to starvation.’ This is a worrying sign that sustained political turbulence is aggravating an already deteriorating economy, with food prices in particular spiralling because of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Tunisia is the country that sparked the Arab Spring in late 2010 and until recently was widely regarded as its only surviving success story. But Saied’s series of undemocratic actions may have buried that trophy irretrievably – though some still hope that the referendum might somehow save the day.

Since 25 July 2021, the president has proceeded steadily down the path of authoritarianism, increasingly monopolising power. He proclaimed a decree governing the state of emergency on 22 September and appointed his own de facto new prime minister. On 12 February, Saied dissolved the Superior Council of the Judiciary, which hired and fired judges, and effectively assumed its powers himself. He dissolved the Parliament on 30 March.

Public freedoms largely remain intact, though some politicians and officials – especially from the main Islamist party, An-Nahda – have been arbitrarily detained. Such actions against the Islamists appear to have buoyed Saied’s popular support in a highly polarised polity. The International Crisis Group recently wrote that polls indicated that 70%-80% of the populace still back him.

This is a reminder that it was in the context of rampant graft, conflict, turbulence and violence among various political factions that he assumed almost sole power on 25 July last year. His move enjoyed the support of many ordinary people, especially anti-Islamists and others who believed a corrupt and self-interested political class was driving Tunisia to ruin.

These sorts of accusations against politicians have often been the pretext for an authoritarian leader to step in and seize power in a coup. This might be explicit and brazen as in the case of a military putsch. But Tunisia’s opposition and some analysts have also labelled Saied’s more implicit unilateral transfer of democratic powers to himself, as a coup.

Matt Herbert, senior expert at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crimes’ North Africa and Sahel Observatory, was cautiously optimistic after Saied’s gambit last year that he’d remain within the bounds of the constitution. But Herbert has lost that hope now.

He notes that Saied’s move to create his own ‘rubberstamp court’ to endorse elections undermines the perceived legitimacy of whatever new constitution the referendum is supposed to validate. More broadly, Herbert notes that ‘the argument that he is still following a constitutional path has become strained to the point of impossibility.’

Saied insists that he is still acting constitutionally as he has invoked provisions governing emergency powers that allow him to rule by decree in certain circumstances. But even if that is so, he seems to be using the constitution to dismantle it, by giving himself more and more powers. And this is happening at a dangerous moment.

‘As Saied advances into this new referendum and attempts to create new political powers and structures in Tunisia, he’s doing so in a situation which is degrading rapidly,’ Herbert says. And Saied has done nothing to remedy the dire economic and social problems that existed before 25 July last year, including high food prices, unemployment and corruption. ‘If anything it’s gotten worse,’ he says, noting that staples such as bread are even less available.

And because of Tunisia’s high dependence on grain imports, the shortages caused by the Ukraine war are pushing the country into a state of acute risk, even outside of Saied’s actions. With the president’s activities in the mix, the threat of social, economic and political volatility this summer is high.

Is this a permanent goodbye to the Arab Spring, considering Tunisia was the only country keeping that flame alive, even if only flickeringly? Herbert says not, believing the Arab Spring should be regarded as a process not a fixed time period. But with its champion in grave jeopardy, it’s hard to see where one should look for new hope.

*About the author: Peter Fabricius, Consultant, ISS Pretoria

Source: This article was published by ISS Today