Are Claims By Russian Experts About Dividing Kazakhstan Between Russia And China At Emba River Going To Come True? – Analysis

There are a number of individuals in Russia, as well as in Ukraine, who have become hugely popular among online communities in the Russian-speaking sector of the Internet after Russia’s military incursion into Ukraine. Among these are Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Russian private military contractor Wagner, and Oleksiy Arestovych, former advisor to the Office of the President of Ukraine. They recently said things that may have deprived many in Moscow, as well as in the Central Asian capitals, of peace. They recently said things that may have deprived many in Moscow, as well as in the Central Asian capitals, of peace.

So let’s first talk about the former one’s words. In an interview with Konstantin Dolgov, a pro-Russian blogger, Yevgeny Prigozhin warned that a revolution, just like in 1917, could rock Russia if its stuttering war effort in Ukraine continues. “First the soldiers will stand up, and after that – their loved ones will rise up. It is wrong to think that there are hundreds of them – there are already tens of thousands of them – relatives of those killed. And there will probably be hundreds of thousands – we cannot avoid that”, he said. According to him, the war in Ukraine is on the verge of failure, one that could lead to a new Russian revolution. “We are in a situation where we can simply lose Russia”, Prigozhin added.

In fact all of those who rule Russia and the Central Asian countries, except for Serdar Berdymukhamedov, the third and current president of Turkmenistan, serving since 19 March 2022, have been through the Soviet high and higher school, and they therefore have some understanding of what is to be expected in case of ‘a revolution, just like in 1917’. In Soviet times, the history of the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia in October 1917 was studied in great detail and everywhere – except maybe in kindergartens and nurseries. That’s why those in the Kremlin and most of their vis-à-vis in the Central Asian capitals can quite well imagine the scale of chaos, anarchy, and destruction that would come in case of ‘a revolution, just like in 1917’.

The Russian decision-makers may still attempt to take measures to prevent such an eventuality. As for their vis-à-vis in the Central Asian capitals, nothing depends on them in such a situation. But in the event that Russia is engulfed in chaos, Central Asia most probably will be affected first of all, since, as Alexander Kadyrbayev, an expert on Russia, China and Central Asia at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said, “all the [political] leaders in the Central Asian countries exist only because they are supported by Russia”. In support of what was said above, it may be recalled that the Kremlin played a key role in restoring order in Kazakhstan during last year’s unrest throughout the country. According to the formal statement by Kazakh President himself, the militants, who had captured 9 regional centers and Almaty, abandoned their plans to seize the presidential residence after having learned about the arrival of the Russian military transport aircrafts to the capital of Kazakhstan. In other words, their offensive actions ceased right after they learned that a Russia-led military alliance stepped in to support the regime in power.

Anyway, Central Asia where Kazakhstan is situated is very sensitive and socio-politically, geopolitically vulnerable region. So it’s no surprise that the Central Asian leaders also are quite much inclined towards cooperation and interaction with other external centers of power with influence in their region. It is to be explained by their desire to avoid, metaphorically speaking, putting all of their eggs in one basket.

So let’s now move onto what Oleksiy Arestovych said in an interview with Mark Feigin, a Russian human rights activist and opposition leader. According to him, China is creating ‘a new defense structure with Central Asia, that is, in the zone of traditional influence of Russia’. From the foregoing, one can only surmise that Kazakhstan, as well as the rest of Central Asia, is going to face some substantial challenges. But this is especially true of the largest country of the region.

Kazakhstan’s economic prosperity relies on trade and investment from Western and Chinese partners, and its military and political stability on the support of Moscow. Astana’s foreign policy has until now been based on seeking a balance of powers to avoid dominance from any one external center of power with influence in the region. A newly emerging geopolitical situation with regard to Central Asia, the formation of which has long been predicted by politicians and experts, threatens to undermine this tripod of Kazakhstan’s sustainable development.

The continued weakening of the Russian Federation both politically and economically may soon make it impossible for Moscow to further ensure the Kazakh ruling regime’s political stability and survival irrespective of whether there will be ‘a revolution, just like in 1917’ in Russia, or not. The circumstances are that while the influence and support of the West can help the Kazakh government to a certain degree, they are not likely to be able in foreseeable future to replace these of Russia and China, between which Kazakhstan is sandwiched. But at the same time, Russia’s presence in the Central Asian country seems to be going to decrease, and China’s one, to increase. It is how the most likely scenario of how the situation might develop looks like.

Yet these all are, albeit reasonable, but just assumptions. Similar analytical assessments and forecasts about the potential growth of activity by China in the Central Asian direction have been made by various experts for a long time. So it makes sense to pay attention to how much of what they had said before came true and vice-versa to get a better understanding of how the situation with regard to Central Asia, including Kazakhstan, will unfold further.

Tadashi Nakamae, president of Nakamae International Economic Research (NIER), in a research piece entitled ‘Three Futures for Japan’ and first published by THE ECONOMIST on September 21, 1998, talked about the possibility of the destabilizing action by China in the period up to 2018, that may be attributable to the need to alleviate the food and energy difficulties of the country and aimed at resource grabbing in Central Asia (and the South China Sea). He then added that the above issues would force the Chinese government to look west and direct their mind to resources of Central Asia.

Tadashi Nakamae made their predictions for the period up to 2018. By the end of it, in June 2018, there were reports in the Kazakh media on how China protects its market from Kazakhstani grain imports. They also mentioned that the leading agrarian countries are literally lining up, wanting to please the Chinese customers. In other words, China has seen no particular need in receiving grain from Central Asia by the end of the designated period. The same can be said of other foodstuffs from the region.

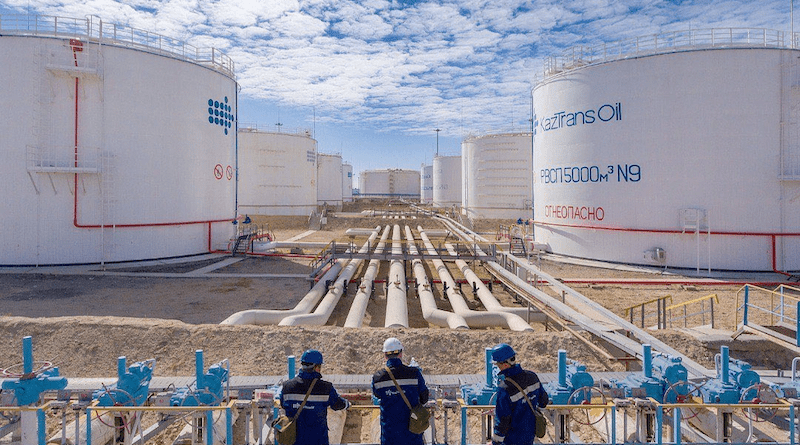

The case of energy is somewhat different. During the period up to 2018, China has managed to establish a stable supply of oil and gas from the territory of the Caspian region through a network of pipelines – the 1,830km (1,140-mile) long Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Kazakhstan-China natural gas pipeline system (known also as Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline) that starts at Turkmen-Uzbek border city Gedaim and runs through central Uzbekistan and southern Kazakhstan before reaching China; and the 2,798km (1,384 miles) long Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline transporting crude from fields located in Western Kazakhstan to the Dushanzi refinery located in the Chinese Xinjiang province.

Through the first one more than 350 billion cubic meters of clean-burning fuel has been transferred to China in 2009-2022. This is a good result. Yet Turkmenistan isn’t going to stop there. Ashgabat has recently unveiled plans to double natural gas exports to China and increase supplies to 65 billion cubic meters per year upon completion of the fourth D string. For comparison: Turkmenistan delivered 34 billion cubic meters of gas to China in 2021. Anyway, Turkmenistan has already become the largest supplier of natural gas to the domestic market of China. And one wouldn’t say the same thing on oil deliveries from Kazakhstan to the Chinese market.

The room to increase supplies via the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline is limited at around 100,000 b/d. This pipeline has got a capacity of 400,000 b/d, of which 200,000 b/d is being used to import Russian crude under the CNPC-Rosneft deal. And yet, crude supplies from Kazakhstan to China, was at just 90,200 b/d in 2021. This is much less than a tenth of the total that Kazakhstan exports.

In any case, it is clear that Tadashi Nakamae’s concerns about the possibility of the destabilizing action by China towards Central Asia in the period up to 2018 were not justified.

As for the claims about the partition of Kazakhstan between Russia and China at the Emba River, made by Oleg Maslov and Alexander Prudnik, well-known Russian political experts, it is probably too early to jump to conclusions – about whether or not they proved to be worth the concern.

Their article entitled ‘Kazakhstan at the beginning of the 21st century is like Poland prior to 1939. Partition of Kazakhstan, or the new Molotov-Ribbentrop plan’ appeared on Polit.nnov.ru January 30, 2007. It said: “The crucial question today is about where the line of division of Kazakhstan between Russia and China will be drawn. It is extremely important for China to have access to the Caspian Sea, so one can predict that the new border between Russia and China will pass along the Emba River at the 47th parallel north. The partition of Kazakhstan along the Emba River and at 48th parallel north is unacceptable for Russia because of Baikonur [cosmodrome]. Other, more flexible partition configurations are possible as well. Everything depends on mutual agreements between the leaderships of China and Russia”.

Yes, it’s been a long time since the appearance of the above article. However, it would be naive to believe that its authors have been the only ones with this attitude towards the future of Kazakhstan. Anyway, their idea has fallen on fertile ground and taken good root in Russia.

Here is a recent example of this. Eadaily, in an article by Albert Hakobyan (Urumov) entitled ‘Who did give the go-ahead for the “the Russian question” to be finally resolved’, said: “The main strategic task [for Kazakhstan] set by Tokayev is as follows: “We must ensure the territorial integrity of Kazakhstan through the completion of the construction of a mono-ethnic state”. In other words: “Get away from Moscow!”… So, there are two options for Russia. The first is to move the actual state border of the Russian Federation moving southward [at the expense of Kazakhstan] as far as possible – along the line: ‘Balkhash – Baikonur – Bekdash’. The second is to federalize Kazakhstan through the creation of two super-regions – ‘the Northern’ and ‘the South’ along the line ‘Ural – Ishim – Irtysh”.

As you can see, Baikonur is mentioned in that case, too. There are a lot of such statements lately, and they are appearing regularly in the Russian media. There seem to be some projects behind all this, developed by the Russian strategists, which provide Moscow’s interference in Kazakhstan’s territories.

This course of events is largely reminiscent of what happened with Ukraine. The only difference is that Kyiv has been accused by the Kremlin’s mouthpieces of having closer relations with the West, and Astana is now suspected by them of having increasingly closer links with Beijing and Ankara, to the detriment of its attachment to Moscow. The latter idea is now being promoted even by well-known Russian opposition figures, such as Gennady Gudkov and Igor Strelkov, the former FSB officers.

The question is: are claims by Russian experts about dividing Kazakhstan between Russia and China at the Emba River going to come true?

Akhas Tazhutov, a political analyst