Czechs Protest Like It’s 1989, Demand Resignation Of ‘Czech Trump’ – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Mitchell Orenstein*

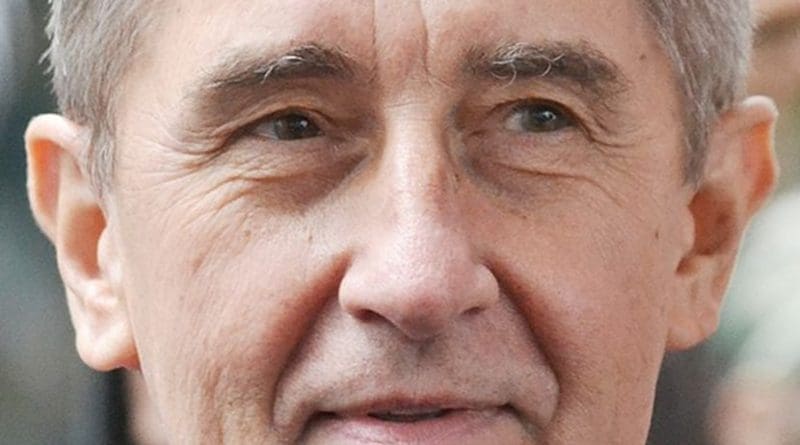

(FPRI) — In the last few weeks, hundreds of thousands of Czechs have poured into the streets to protest the corrupt rule of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, the “Czech Trump.” The scenes are reminiscent of 1989. The largest demonstration took place on June 23 on Letna plain, an enormous park on a bluff overlooking Prague, where a previous generation faced down the communist dictatorship. Others took place in Wenceslas Square, where the 1989 protests also originated.

The slogans of this wave of protest are reminiscent of 1989: “Resign,” “We’ve had enough,” “Babiš, the biggest crook in Czech politics since 1989,” and, “Dear EU, Don’t Feed the Oligarch.”

The Czechs protesting today feel like they are fighting for democracy, just like in 1989. They draw parallels between Babiš and the communist dictators of old. Babiš is widely believed to be a former agent of the communist-era secret police who took advantage of his connections to become one of the richest men in the country. For many Czechs, he represents a return of cynical late-communist rule, with its corruption, propaganda, and anti-democratic politics.

These demonstrations were sparked by the European Union accusing Babiš of fraud. Like President Donald Trump, Babiš still owns his business empire, though it is held in trust. The EU fraud office found that Babiš defrauded the EU by applying for and obtaining a grant intended for small business—he owns a large conglomerate—by hiding his ownership stake in the “Stork’s Nest” conference center. In April, the Czech police recommended trying him for fraud. Protests also started when Babiš appointed a new justice minister to stop the case from proceeding.

Just Another Fraudulent Populist?

Czech protests have captured the popular imagination in Europe and beyond. They seem to represent a people standing up to a wave of populist oligarchs who have seized power in country after country after the global financial crisis, riding a wave of discontent with liberal elites.

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of Hungary blazed this trail in Central Europe, winning a massive victory in 2010 on a platform of Hungarian nationalism, opposition to foreign banks and the International Monetary Fund, and an “Eastern winds” economic policy that would balance between Russia, China, and the West. The appeal was that Hungary would not be dominated by Western institutions such as the EU, but forge its own nationalist path to economic development, providing greater opportunities to average Hungarians.

Babiš followed suit. Recognizing that Czechs were tired of corruption, he founded a new party, ANO (Yes) 2011, and ran on an anti-corruption ticket. He promised to be a new face—a man with substantial business experience and free from political interests. He promised that, being already rich, he would not use the office to enrich himself, but instead to provide strong technocratic rule. His party entered parliament in 2013 as the second largest in the country.

From the beginning, Babiš suffered from allegations of corruption. He sought to cover up his extensive links to the former communist State Security police. He allegedly defrauded the EU. His Agrofert conglomerate allegedly grew based on corrupt state deals. He bought two of the leading newspapers in the country to support his political agenda. And when that was not enough to prevent reports of corruption surfacing in the “Stork’s Nest” case, he allegedly paid to have his own son kidnapped and deported to Crimea to prevent him from testifying.

Enough is Enough?

Today, Czech politics is defined by a struggle between the forces of nationalist populism, which accepts a certain degree of corruption and anti-democratic control, and liberals in the tradition of 1989 who want a democratic society and rule of law in addition to growing prosperity. That is the battle being fought out on Letna plain. And not only there, but across today’s EU, in Italy, in Hungary, in Poland, even in the United Kingdom.

Nationalist populists have something important to say. They oppose the liberal economic policies enacted since 1989 that produced great results for the new rich and upper middle classes, but at the expense of withdrawing social protections for the poor and creating a precarious life for average earners. They want more jobs and more opportunities for average co-nationals and believe that the state should act to provide them.

Nationalist populists have coupled this emphasis on nationalist economic policy with determined opposition to minority groups that they perceived to be a threat to national identity. In the Czech Republic, that has meant giving space for anti-Roma attacks and opposition to Muslim immigration, which was practically nil. Babiš, for instance, has mirrored Trump by promising to make the Czech Republic great again, with a renewed patriotism.

Yet, national populists also brought a diminished respect for human rights, rule of law, and democratic procedure, which millions who fought for the revolutions of 1989 hold dear. And a massive level of corruption starting at the top.

This sets up predictable battle lines in country after country between the imagination of a revived populist nationalism and a utopian world of prosperous liberal democracy. These are the forces on the two sides of the barricades being manned in Prague. Both are determined and confident.

But both sides suffer from considerable blind spots. Liberal democrats have failed to respond to rising inequality and to provide a fair economy for the majority. Populist nationalists have failed to respect the fundamental institutions of democracy and rule of law, threatening the human rights of all, but particularly minority groups.

As a result, this conflict between a corrupt, crony patriotism and an insensitive, over-confident liberalism will continue to divide the West—like the Czech Republic—for years to come.

*About the author: Mitchell Orenstein is a Senior Fellow at FPRI’s Eurasia Program and Professor and Chair of Russian and Eastern European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Source: This article was published by FPRI