Spotlight Focuses On Romney’s Mormon Faith

By VOA

By Jerome Socolovsky

At a Salt Lake City theme park that showcases the area’s pioneer past, a mother and her daughters duck into a log cabin. Inside, park staff in 19th century dress are talking about the hardships their ancestors faced on the frontier.

Cheryl Quist brought her family to This is the Place Heritage Park to learn their history, and she gets into a discussion about anti-Mormon prejudices. She says Mitt Romney’s candidacy for president means Americans are finally learning “what our religion is really about.”

Mormons see themselves as fervently patriotic. The U.S. Constitution is sacred according to their beliefs. And their church, formally known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, emphasizes all-American values such as optimism and self-reliance.

But unlike any other religion founded in this country, Mormonism has been met with hatred and persecution – from the murder of its prophet, Joseph Smith Jr. in 1844 – to the waves of attacks that drove his early disciples westward.

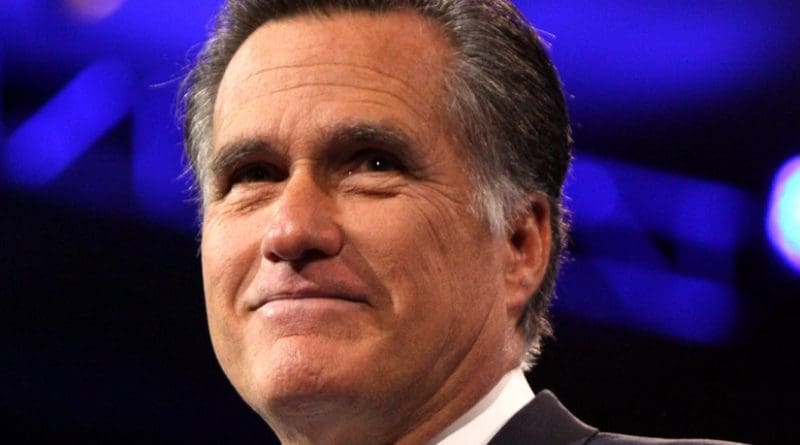

Romney is the first Mormon to win a major party’s nomination. But some Mormons say the candidate’s hesitation to talk about his faith is rooted in the fear that it will be used against him.

“Mormonism is an easy target because we have so many different ideas than the rest of mainstream Christianity,” says Tom Kimball of Signature Books, a Salt Lake City publisher focused on scholarly books about Mormon history.

Biblical story on American soil

In the 1830s, after a series of visions, Joseph Smith said he was given a mission to restore the early Christian church. He preached a theology in which people could become exalted like God, and he published a scripture called the Book of Mormon.

It tells that after his resurrection, Jesus made an appearance in the Americas to remnants of the lost tribes of Israel. Smith also placed the Garden of Eden in present-day Missouri.

There is no historical evidence to back these claims, and the church’s early history of polygamy – it was officially banned in 1890 – often inflamed its critics more than anything else.

But Kimball says part of the new faith’s appeal was that it brought the biblical story to American soil and made God approachable.

“The cool thing about Mormonism,” says Kimball, “is that it was a rational theology that you could put your arms around. And it was a hopeful and exciting theology… we could become exactly like our Father in heaven and live with him.”

Today, Mormonism is one of the world’s fasted growing faiths with 14 million adherents, including 6 million in the U.S. But its theology is taken as heresy by some of the very people who have formed the voter base for the Republican Party – Evangelical Christians.

Mormonism’s Evangelical critics

Rob Sivulka leads Courageous Christians United, a group that pickets Salt Lake City’s Temple Square. Seat of the Latter-day Saints’ world headquarters, Temple Square is to Mormons more or less what Mecca is to Muslims or the Vatican to Roman Catholics.

On a recent evening, as crowds were heading to a public rehearsal of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, Sivulka stood outside the gate and shouted: “Joseph Smith lied when he said you’ll all grow up to become gods!”

Sivulka’s primary aim is to convert Mormons, who themselves spend two years of their life proselytizing around the globe. But he says he also needs to protect Christians from Mormon missionaries who say theirs is the true faith.

“I’m concerned about my own Christian brothers and sisters that are getting hoodwinked into joining what I would call a cult,” Sivulka said. “It’s something that appears to be very Christian, but turns out to be a pseudo-Christian group.”

LDS church leaders reject this. They say Mormons are Christians because they regard the Bible as scripture and believe in Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior. And they say their beliefs about the nature of God and man are rooted in the Bible.

But polls in recent years have ranked Mormonism about equal with Islam as the faiths least liked by Americans.

Sivulka concedes that despite his polemics, he generally agrees with Mormons’ views on abortion, same-sex marriage and other social values issues. So, he says, he will vote for Romney in November.

Why Mormons smile a lot

And lately, the Republican nominee has started to give glimpses of his faith, allowing some reporters into his church several weeks ago. In the early 1980s, Romney became a member of the faith’s unpaid clergy, and was later appointed “stake president,” or leader of Boston-area congregations.

His image as a caring father and husband, which his campaign has promoted, has a lot to do with the traditional Mormon family lifestyle.

In a suburban home near Salt Lake City, Tami and Tom Larsen gather their children in their living room on Monday evenings for prayer, gospel and games. It is part of a tradition known as Family Home Evening, a time set aside each week to spend time together.

“We believe in eternal families,” says Tami Larson, adding that Mormonism is a faith that makes its adherents happy. In fact, its path to salvation is also known as the “Plan of Happiness.” And non-Mormons often wonder why Mormons always seem cheerful and smiling.

“I think that the best revenge has always been to be happy,” says Kimball, the book publicist. “And as Mormons were persecuted and pushed out of their cities and homes back east, they tried to come here and carve a community – a modern community – out of this desert, in the middle of nowhere.”

At his office in one of the oldest houses still standing in Salt Lake City, Kimball says happiness – and success – were ways “to show the world that, ‘Hey, here we are, we’re God’s people.'”