Expert’s Latest Investigation Dispels Myths About Pius XII And Rome’s Jews

By CNA

By Andrea Gagliarducci

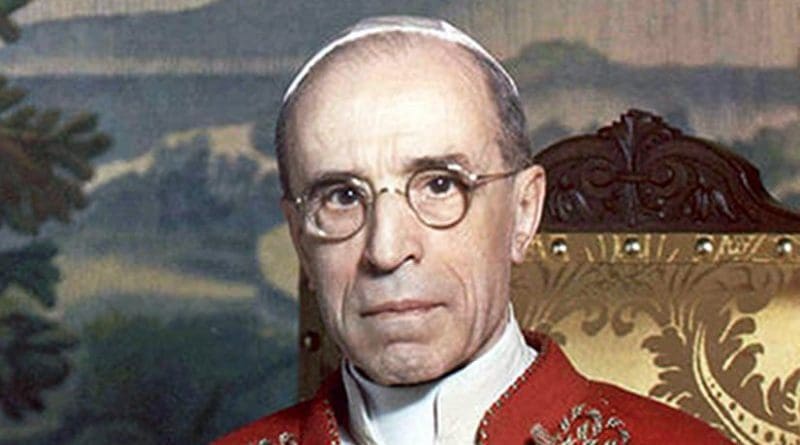

Pope Pius XII was not silent in front of the Shoah nor inactive. He was, instead, very much committed to saving Jewish families, spoke out constantly against the Nazi Regime, and set up a series of formal and informal initiatives that show that he was anything but “Hitler’s Pope.”

These are the conclusions of a series of investigations on archive material carried out by Deacon Dominiek Oversteyns, of the Spiritual Family “The Work.”

Oversteyns’ investigations include “The Book of Memory” by Liliana Picciotto, a Jewish researcher, which collects the names of all deported and killed Italian Jews; the “History of Italian Jews under Fascism” by Renzo De Felice, which outlines the history of 148 convents that saved many Jews, and the Vatican archives on Pius XII now open to the public.

A former engineer, Oversteyns crossed data and used the math technique of extrapolation to analyze the numbers of killed and deported Italian Jews. His studies, presented in a series conferences and which he shared with CNA, shed light on Pius XII’s intervention before and after the Nazi raid in Rome’s Jewish ghetto.

According to his study, there were 8,207 Jews in Rome before the Nazi raid on the Jewish ghetto on Oct. 16, 1943.

Out of these, 1,323 — or 16% — found refuge prior to the raid. Eighteen went to the Vatican extraterritorial properties, 393 to villages in the mountains around Rome, 368 to the private homes of friends, 500 to 49 different Roman convents, and 44 to parishes and pontifical colleges in Rome, Oversteyns reported.

Pius XII was also able to help 152 Jews hidden in private homes under the protection of DELASEM, the Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants. In all, Pius XII gave support to some 714 Jews.

The study also points out that Pius XII welcomed at least 30 Jewish scholars to the Vatican, where they worked and carried out their research in the Vatican Museums and Archives after being fired from their institutions due to racial laws. Among them were Hermine Speier, who began working in the Vatican as early as 1934; Fritz Volbach, hired in the Vatican in 1939, and Erwin Stuckold.

Eight different testimonies reveal how Pius XII asked at least 49 convents to hide and house Jews, and declared those convents to be extraterritorial areas under the authority of the Vatican, Oversteyns found.

According to Oversteyns, these numbers demonstrate that Pius XII was actively in favor of Jews well before the Nazi raiding of the ghetto in 1943. That Saturday, at dawn, 365 Nazi soldiers rounded up 1,351 Jews. Of them, 61 were released immediately, and another 258 were released after they were kept in a military college. Finally before the train departed from Rome’s Tiburtina Station for Auschwitz, two other Jews were released.

A little known fact is that Pius XII and his collaborators were responsible for the release of 249 Roman Jews on that day, about one-fifth of those rounded up, Oversteyns said.

Early in the morning of the day of the raid, according to Oversteyns’ documents, Pius XII contacted the German ambassador Ernst von Weizsäcker to convince him to call Berlin and stop the roundup, but the ambassador did not act, Oversteyns said.

Then, through Father Pancratius Pfeiffer, a well-regarded German priest superior of the Salvatorians, Pius XII contacted General Reiner Stahel, head of the German army in Rome at that time, who telephoned Himmler directly and convinced him to stop the raid at 12 noon. At the same time, the SS commander Dannecker received instructions from Berlin to free all Jews in mixed marriages and in service of “Aryans.”

The raid in the central area of the city ended between 11 and 11:20 a.m., while in the outskirts of Rome, it ended by 1:20 p.m. Of the 1,030 Jews deported to Auschwitz on Oct. 18, only 16 would return after the war, according to Oversteyns.

The Germans kept their activity of searching, arresting, and deporting Jews even after the raid. From Oct. 18, 1943, to January 1944, 96 Jews were arrested, according to Oversteyns. Then, from February 2, 1944 onwards, 29 Jews were arrested in five Catholic colleges and 19 Jews in the abbey of San Paolo, which was an extraterritorial territory of the Vatican.

In March 1944, the situation became even more severe. From March 21 to April 17, about 10 Jews were arrested and deported daily. And from April 28 to May 18, five Jews were arrested and deported daily. Finally, the Jews had no choice but to flee or go underground.

Pius XII hid 336 Jews in parishes and diocesan hospitals, Oversteyns found. At the same time, he continued to send food and financial aid to DELASEM.

Sources show that there were just 160 Jews in the Vatican and its 26 extraterritorial locations. This is because Pius XII’s strategy was to hide Roman Jews in small groups in convents in Rome.

From Sept. 10, 1943, to June 4, 1944, Pius XII carried out 236 interventions in favor of Jews arrested in Rome and on their way to deportation. Following his interventions, 42 arrested Jews were released.

In addition to the official channel of the Secretariat of State (through the then-substitute Giovanni Battista Montini, who would later become Pope Paul VI), Pius XII widely used the informal channel established by Fr. Pfeiffer.

Father Pfeiffer, according to documents, visited the Secretariat of State every other day during the eight months of intense Nazi persecution in Rome. In those meetings, he gave information on those arrested and received requests for release.

Oversteyns says that more clarity about Pius XII’s commitment to Roman Jews will come to light now that the Vatican archives of his pontificate have been open to investigators.