Organizing McDonalds And Walmart, And Why Austerity Economics Hurts Low-Wage Workers The Most – OpEd

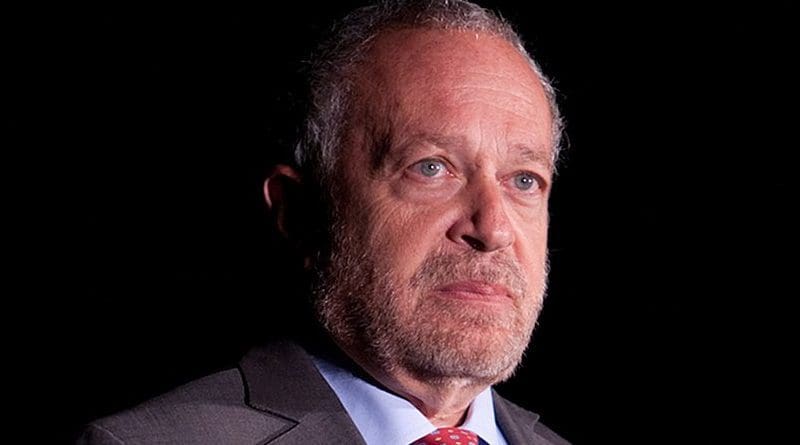

By Robert Reich

What does the drama in Washington over the “fiscal cliff” have to do with strikes and work stoppages among America’s lowest-paid workers at Walmart, McDonald’s, Burger King, and Domino’s Pizza?

Everything.

Jobs are slowly returning to America, but most of them pay lousy wages and low if non-existent benefits. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that seven out of 10 growth occupations over the next decade will be low-wage — like serving customers at big-box retailers and fast-food chains. That’s why the median wage keeps dropping, especially for the 80 percent of the workforce that’s paid by the hour.

It also part of the reason why the percent of Americans living below the poverty line has been increasing even as the economy has started to recover — from 12.3 percent in 2006 to 15 percent in 2011. More than 46 million Americans now live below the poverty line.

Many of them have jobs. The problem is these jobs just don’t pay enough to lift their families out of poverty.

So, encouraged by the economic recovery and perhaps also by the election returns, low-wage workers have started to organize.

Yesterday in New York hundreds of workers at dozens of fast-food chain stores went on strike, demanding a raise to $15-an-hour from their current pay of $8 to $10 an hour (the median hourly wage for food service and prep workers in New York is $8.90 an hour).

Last week, Walmart workers staged demonstrations and walkouts at thousands of Walmart stores, also demanding better pay. The average Walmart employee earns $8.81 an hour. A third of Walmart’s employees work less than 28 hours per week and don’t qualify for benefits.

These workers are not teenagers. Most have to support their families. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median age of fast-food workers is over 28; and women, who comprise two-thirds of the industry, are over 32. The median age of big-box retail workers is over 30.

Organizing makes economic sense.

Unlike industrial jobs, these can’t be outsourced abroad. Nor are they likely to be replaced by automated machinery and computers. The service these workers provide is personal and direct: Someone has to be on hand to help customers and dole out the burgers.

And any wage gains they receive aren’t likely to be passed on to consumers in higher prices because big-box retailers and fast-food chains have to compete intensely for consumers. They have no choice but to keep their prices low.

That means wage gains are likely to come out of profits – which, in turn, would affect the return to shareholders and the total compensation of top executives.

That wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

According to a recent report by the National Employment Law Project, most low-wage workers are employed by large corporations that have been enjoying healthy profits. Three-quarters of these employers (the fifty biggest employers of low-wage workers) are raking in higher revenues now than they did before the recession.

McDonald’s — bellwether for the fast-food industry — posted strong results during the recession by attracting cash-strapped customers, and its sales have continued to rise.

Its CEO, Jim Skinner, got $8.8 million last year. In addition to annual bonuses, McDonald’s also gives its executives a long-term bonus once every three years; Skinner received an $8.3 million long-term bonus in 2009 and is due for another this year. The value of Skinner’s other perks — including personal use of the company aircraft, physical exams and security — rose 19% to $752,000.

Yum!Brands, which operates and licenses Taco Bell, KFC, and Pizza Hut, has also done wonderfully well. Its CEO, David Novak, received $29.67 million in total compensation last year, placing him number 23 on Forbes’ list of highest paid chief executives.

Walmart – the trendsetter for big-box retailers – is also doing well. And it pays its executives handsomely. The total compensation for Walmart’s CEO, Michael Duke, was $18.7 million last year – putting him number 82 on Forbes’ list.

The wealth of the Walton family – which still owns the lion’s share of Walmart stock — now exceeds the wealth of the bottom 40 percent of American families combined, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute.

Last week, Walmart announced that the next Wal-Mart dividend will be issued December 27 instead of January 2, after the Bush tax cut for dividends expires — thereby saving the Walmart family as much as $180 million. (According to the online weekly “Too Much,” this $180 million would be enough to give 72,000 Wal-Mart workers now making $8 an hour a 20 percent annual pay hike. That hike would still leave those workers making under the poverty line for a family of three.)

America is becoming more unequal by the day. So wouldn’t it be sensible to encourage unionization at fast-food and big-box retailers?

Yes, but here’s the problem.

The unemployment rate among people with just a high school degree or less – which describes most (but not all) fast-food and big-box retail workers – is still in the stratosphere. The Bureau of Labor Statistics puts it at 12.2 percent, and that’s conservative estimate. It was 7.7 percent at the start of 2008.

High unemployment makes it much harder to organize a union because workers are even more fearful than usual of losing their jobs. Eight dollars an hour is better than no dollars an hour. And employers at big-box and fast-food chains have not been reluctant to give the boot to employees associated with attempts to organize for higher wages.

Meanwhile, only half of the people who lose their jobs qualify for unemployment insurance these days. Retail workers in big-boxes and fast-food chains rarely qualify because they haven’t been on the job long enough or are there only part-time. This makes the risk of job loss even greater.

Which brings us back to what’s happening in Washington.

Washington’s obsession with deficit reduction makes it all the more likely these workers will face continuing high unemployment – even higher if the nation succumbs to deficit hysteria. That’s because cutting government spending reduces overall demand, which hits low-wage workers hardest. They and their families are the biggest casualties of austerity economics.

And if the spending cuts Washington is contemplating fall on low-wage workers whose families are under the poverty line – reducing not only the availability of unemployment insurance but also food stamps, housing assistance, infant and child nutrition, child health care, and Medicaid – it will be even worse. (It’s worth recalling, in this regard, that 62 percent of the cuts in the Republican budget engineered by Paul Ryan fell on America’s poor.)

By contrast, low levels of unemployment invite wage gains and make it easier to organize unions. The last time America’s low-wage workers got a real raise (apart from the last hike in the minimum wage) was the late 1990s when unemployment dropped to 4 percent nationally – compelling employers to raise wages in order to recruit and retain them, and prompting a round of labor organizing.

That’s one reason why job growth must be the nation’s number one priority. Not deficit reduction.

Yet neither side in the current “fiscal cliff” negotiations is talking about America’s low-wage workers. They’re invisible in official Washington.

Not only are they unorganized for the purpose of getting a larger share of the profits at Walmart, McDonalds, and other giant firms, they’re also unorganized for the purpose of being heard in our nation’s capital. There’s no national association of low-wage workers. They don’t contribute much to political campaigns. They have no Super-PAC. They don’t have Washington lobbyists.

But if this nation is to reverse the scourge of widening inequality, Washington needs to start paying attention to them. And the rest of us should do everything we can to pressure Washington and big-box retailers and fast-food chains to raise their pay.