India’s Home Minister In China: What Is The Takeaway? – Analysis

By SAAG

By Bhaskar Roy*

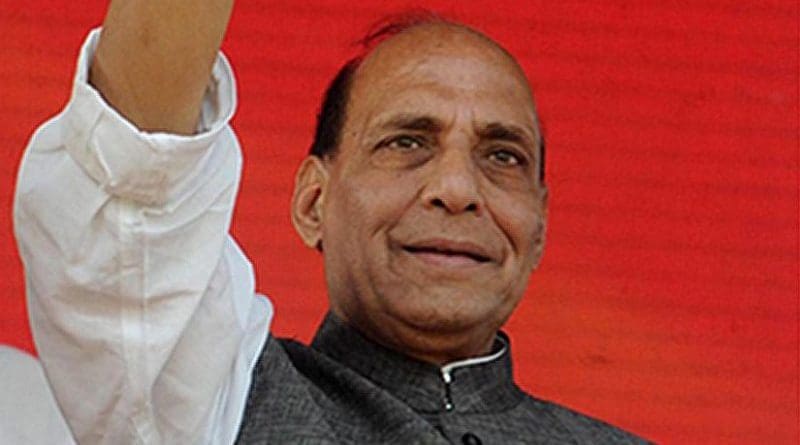

India’s Home Minister Rajnath Singh’s visit to China (November 18 to 23) can be seen as a testing step to see China’s real commitment to earnestly combat terrorism in its entirety. Till now, Beijing’s track record on this issue has been patchy, narrowly focussed and politically manoeuvred.

The Chinese side was correct on protocol and the right amount of warmth. Singh called on Premier Li Keqiang, met security Czar Meng Jianghu, and had working discussion with this counterpart Guo Shengkun, State Councilor and Minister of Public Security.

The preamble to the seven-point joint statement says that the two sides reiterated their strong condemnation of and resolute opposition to “terrorism in all forms, its forms and manifestations and committed themselves to cooperate on counter terrorism”.

This is the central phrase in the joint statement that will be tested in due course on counter terrorism and will eventually have to expand and define terrorism as a whole. Will support to so-called liberation armed struggle by groups in other countries be included in the definition of terrorism?

The joint statement gives glimpses into the intentions of the two countries. It is a negotiated document between the two sides and views of the two sides are accommodated, unless there are major differences. The recent rise of the Islamic state (IS) threatening all and the devastating attack on Paris has forced even reluctant participants to come out against terrorism.

The joint statement agrees to hold meetings and contacts between the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and the Chinese Ministry of Public Security (MSP) periodically. But holding meetings between two Ministers every two years in Beijing and New Delhi suggests somewhat dilution of the spirit of the intention. Nevertheless, an agreement on mechanism has been established officially and openly for the first time.

Paragraph 3 of the joint statement is most important. It envisages exchanging information on terrorist groups and coordinating positions on anti-terrorism endeavours at regional and multilateral levels and supporting each other.

These endeavours would require a more precise and agreed definition of terrorism and terrorist groups.

Are organisations like Lashkar-e-Taiba (LET), Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM), and the Haqqani network terrorist organisations?

Are Hafeez Saeed, Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi terrorists? Is Pakistan’s intelligence organisation the ISI a promoter of terrorism? China will be hard put to lend clarity to these questions.

In August this year, China nixed India’s efforts in the UN for a censure of Pakistan for releasing LET commander Lakhvi, who executed the terrorist attack on Mumbai on 26 November 2008 (26/11) in which 167 people were killed, with a ‘technical hold’. Prime Minister Narendra Modi tried to take up the issue with President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the Ufa conclave in Russia, but he was snubbed.

China’s focus has been solely on the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), an Uighur separatist organisation fighting in the country’s South-Western Xinjiang-Uighur Autonomous region. China has for long been aware that the ETIM received safe havens, arms training and Islamic indoctrination from Pakistani radical terrorist organisations. The Chinese told late Pakistan’s Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto when she visited China in 1992. They also told her that she would not be able to do anything as the ISI was involved.

The closest that China came to charge Pakistan on supporting the ETIM was in 2008 in the run up to the Beijing Olympics. Subsequently, with China’s “strike hard” campaign in Xinjiang and pressure on Pakistan, Islamabad either killed or handed over some ETIM leaders to China.

There is huge question here. Why does China deal with Pakistan so delicately when it has also suffered from Pakistan’s sponsored religious terrorism? The core of the answer is very clear. Pakistan has been and will be of immense strategic importance to China. Pakistan’s policy to “bleed India with a thousand cuts” worked to China’s interest and was abetted by China. This is why the ‘technical hold’ on Lakhvi.

For more than two decades a line existed between India and China through intelligence channels. India provided tonnes of information on Pakistan intelligence’s nexus with its state sponsored terrorist organisations, but to no avail. Will china’s position shift after their agreement with India? This should be proved soon.

*The writer is a New Delhi based strategic analyst. He can be reached at e-mail [email protected]