‘Pray For Paris’: Epistemology And Political Economy Of Global Terrorism – Analysis

By Odomaro Mubangizi*

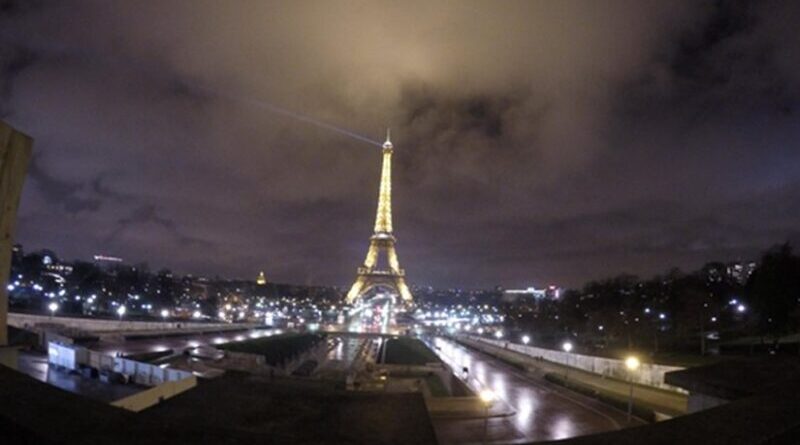

Friday, November 13, 2015 witnessed yet another horrific terrorist attack in Paris. 129 people were killed in this attack and over 300 were badly wounded. The whole world is shocked at the sheer brutality of such attacks that end the lives of innocent civilians without discrimination. The US Secretary of State termed the attackers “psychopathic monsters.” Just like the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in 2001, Embassy bombings in Nairobi in 1998, and the Nairobi Westgate attack in 2013, the terrorist attack in Paris leaves many wondering what is behind all this brutal acts by extremist Islamists. Terrorism has even evolved into what is now termed Islamic State ideology or ISIS. Can we now talk of an epistemology and political economy of terrorism? Has terrorism metamorphosed into a complex knowledge system with an elaborate political theory, whose elements have to be comprehended before strategies can be devised to deal with this global menace that is a major threat to the Westphalia state system and liberal democracy?

I suggest that a discourse on global terrorism be grounded in the conceptual and theoretical frameworks of global civil society, global governance, cosmopolitcs, political epistemology and global political economy. The emergency of global terrorism calls for a new paradigm in international relations theory, since new actors have emerged in the global scene to contest the hitherto dominant role of the nation-state in international affairs, especially in matters of war, security and violence.

The fact that the extremist jihadist Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a 28-year-old Belgian of Moroccan origin, could plan attacks in Paris, demonstrates how terrorism is indeed thriving in the context of increasing globalization. Consider the many variables at stake: a Muslim of Moroccan origin who bears Belgian citizenship coordinating terror attacks in Paris. This is what makes it difficult to deal with global terrorism. Actors in global terrorism are extremely sophisticated individuals, with complex profiles.

The almost four-year war in Syria has given rise to the Islamic state. Extremist jihadists leave Western countries to join ISIS in Syria and return to these countries to cause havoc. Just as France was recovering from the Paris terrorist attack, extremists attacked Radisson Blu Hotel in Bamako, Mali, and killed about 20 tourists after a siege lasting seven ours. What do we make of these wanton terrorist attacks that have shaken the entire world system?

There is enough empirical data and commentaries to assist in theorizing about terrorism. I suggest a pentagonal (pun unintended) framework to address the multifaceted phenomenon of global terrorism. The five dimensions of this framework are: 1) Power of epistemology and epistemology of power; 2) Power of the weak and weakness of the powerful; 3) Terror of Globalization and globalization of terror; 4) Commodification of violence and violence of commodities; 5) War on terror and terror of war. Note that in each dimension a thesis is followed by an antithesis. Following the Hegelian triadic movement of history of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, the dialectic compels us to look for a synthesis, which I suggest to be cosmopolitics as a new international political economy. All the developments around global terrorism, failure of powerful states to address the menace of violent extremism, global poverty and environmental crisis, seem to point to the uncomfortable truth that the Westphalian state paradigm has outlived its usefulness.

POWER OF EPISTEMOLOGY AND EPISTEMOLOGY OF POWER

There is a common adage that “knowledge is power.” But we can also add that “power is knowledge.” Epistemology is a theory of knowledge, and so when we apply epistemology to global terrorism, we attempt to theorize about terrorism, exploring its nature and dynamics based on the bits of data we have. It should be stated at the outset that the grand theory behind terrorism is still a work in progress. Since terrorism does not have a clearly defined central location like in a state system, it can be defined as decentralized power and violence. But we must hasten to add that terrorism follows a certain complex logic and system of knowledge that is yet to be fully grasped.

The knowledge system under which terrorists operate defies the conventional Western epistemological system. This is why security and intelligence agencies find it very difficult to pre-empt terror attacks. Following the emergency of terrorism especially after 9/11, the dynamics of power have changed but most political leaders have failed to fully understand this radical shift in the conception of power. Faced with this challenge Joseph Nye came up with the new concept of “soft power” which he defined as “…the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments. It arises from the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideals, and policies.”[1]

If one knows the nature and dynamics of terrorism, then one would apply appropriate strategies to deal with it. The success or failure of strategies against terrorism demonstrate whether the phenomenon of terrorism is well grasped. This point is well captured by Nye when commenting on America’s war in Iraq: “The four-week war in Iraq in the spring of 2003 was dazzling display of America’s hard military power that removed a tyrant, but it did not resolve our vulnerability to terrorism. It was also costly in terms of our soft power—our ability to attract others to our side.” [2] Concepts are the tools of trade of epistemology, and concepts are powerful tools, like the concept of “soft power.”

Founders of the realist school of international relations put emphasis on hard power, some of them such as Niccolo Machiavelli even advised political leaders that it is better to be feared than to be loved. Thomas Hobbes added that covenants without swords are mere words. It is this framework of power that has dominated world politics for centuries. But with the growth of information technology the dynamics of power have changed to the effect that those who wield information, and hence influence, have enormous power. A computer or an Android smart phone gives as much or even more power than a gun.

Power can also be acquired because of beliefs and convictions. Consider the follower of Osama bin Laden who is ready to die for a terrorist cause just on the grounds of Osama’s objectives. This is where belief systems or worldviews have a great impact on people. This means that terrorist groups also use “soft power”—they persuade recruits that they have a better worldview than the countries or people they are targeting. Unsurprisingly, terrorists also use information technology to pass on their message.

It is clear that new forms of power also generate new ways of knowing. This is what ICT has done. Soft power has been discovered just as information technology became a commonplace. As new power centers emerge, new knowledge systems emerge. With the emergence of terrorism, new epistemologies have also emerged. Information technology makes borders more porous and the flow of knowledge is made easier, but also hard to control. This is why the fight against terrorism is much more difficult.

POWER OF THE WEAK AND WEAKNESS OF THE POWERFUL

If as Hannah Arendt claims “…every decrease in power is an open invitation to violence”, then terrorism might be a result of disempowerment. So violence, in this case terrorism, is a weapon of the weak to inflict maximum pain and fear on the powerful. This can be verified from the type of weapons and homemade bombs that terrorists use: pressure cookers, soft-drink cans, shoes, cell phones, petrol, etc. Frequent flyers know the inconvenience they go through as they are searched at airports and their items confiscated: tooth paste, lotions, shavers, water, etc. For any of these simple items can be turned into a weapon of mass destruction.

No one ever thought that a small item such as a toothpaste tube, a cell phone or a plastic water bottle can be used to blow up a plane, or set an entire airport on fire. The shear ingenuity of terrorists leaves the mighty scared. The options for unleashing large -destruction using minimum resources are unlimited. Intelligence and security personnel are on their toes never sure what new strategies will be used to carry out terrorist attacks. What is more frustrating is the constant change of strategy: after using planes to destroy the twin towers, this method was abandoned; after targeting shopping malls, this method was shelved; suicide bombs have persisted for a while; the pressure cooker bomb used during the Boston Marathon attack has not been use since then. This means that security agencies have no clue what the next bomb will be made of. Fighting terrorism has become like fighting a moving target.

As Karl Von Clausewitz labeled war as “the continuation of politics by other means,” terrorism as war of the weak who lack a sate machinery is a continuation of politics by other means. Engels went further to define violence as the accelerator of economic development. It should therefore come as no surprise that terrorism has become a huge industry as nations invest in massive security and defense programs to counter terrorist attacks. The emergency of terrorism has helped raise the question of power among nations. Who is powerful? Hannah Arendt reflecting on violence made the following reminder worth pondering: “…power cannot be measured in terms of wealth, that an abundance of wealth may erode power, that riches and well-being of republics—an insight that does not lose in validity because it has been forgotten, especially at a time when its truth has acquired a new dimension of validity by becoming applicable to the arsenal of violence as well.”[3]

According to Hobbes, one of the main rights of a sovereign is that of making war and peace. Now that terrorist groups can wage war against sovereign states, the claim that the state has monopoly over the use of force needs rethinking. The map of terrorist activities across Africa is well painted by Baffor Ankomah: “From the east, in Somalia, where al-Shabab has been laying waste to human life and property all the way into Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia, to Nigeria where Boko Haram thinks boarding school children are legitimate targets of attack in addition to the indiscriminate murder of civilians, to the Maghreb and Sahel countries where Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliates and competitors have gone as far as launching a full-scale hot war in Mali after years of attacks in Algeria, Mauritania, Niger and Chad, the definition of a ‘terrorist” on the continent has changed dramatically from how Mrs Thatcher and Mr Reagan saw it in their days, to a dangerous extremist prepared to kill, maim and destroy.”[4]

Terrorist groups act like multinational corporations by creating affiliates under different labels in various countries. They are truly a global phenomenon, but they execute their plans locally.

So the strength of the weak non-state terrorist groups lies in their ability to make strong strategic allies across borders using religion as a glue for unquestioning loyalty and external funding to oil their operations. Terrorists can move from Belgium to France, from Chad to Mali, from Somalia to Kenya, from Kenya to Uganda, from Sudan to Somali, from Afghanistan to Somalia, changing names and passports at will. Since these terrorists have incredible flexibility in their strategies, governments are unable to predict their moves or gather credible intelligence so as to pre-empt terror attacks. This is where lies the weakness of the powerful nations. Terrorists also find sanctuary in fragile or failed states. This is why jihadists are being trained in Iraq, Syria, Somalia and Afghanistan. Failed or fragile states provide suitable routes for smuggling illegal guns, and recruiting grounds for unemployed youth.

The powerlessness of the powerful amidst increasing internationalization of the state is well articulated by Yoshikazu Sakamoto using the G7 as a case study thus: “The cause of its (G7) failure is structural. First, the problems—such as nuclear disarmament and proliferation, strengthening of the United Nations, world financial instability, world structural unemployment, global environmental regulations, and so forth—that confront the big powers are of such global consequence that they can no longer be adequately dealt with within the framework of the state system or the mere total sum of the statecraft of individual states.”[5] While the inefficiencies and incompetence of the state and state system are too glaring for all to see, both and advanced and weak states of the South continue to do business as though they can handle global challenges. With increasing internationalization, sovereign states have lost their… authority, competence, credibility and legitimacy…”[6]

TERROR OF GLOBALIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION OF TERROR

So can terrorism be situated in the broader discourse of globalization or even trace its roots therein? A question was put to a world expert on Islam and interreligious dialogue Thomas Michel, S.J. as to what he would say the root causes of religious fundamentalism were. This is how he responded: ‘Well, the root causes of religious fundamentalism, I think, are basically a rejection of the values of modernity—our liberal values, you might say, values that came out of European environment. From the fundamentalist point of view, these liberal values guide and control government ministries, the universities, the mass media, the arts, films and that kind of thing. And they feel that liberal values create a kind of human-centered universe, but they want to replace this with a God-centered universe where God’s will is central.”[7] So terrorism born of religious fundamentalism, it seems, is a protest and resistance against Western liberal ideology. Has globalization brought about marginalization of peripheral perspectives, and the only alternative left is to hit back with the decentralized violence we now term “terrorism”?

On the question of whether terrorism should be treated like a criminal act, Mahmood Mamdani observes: “The distinction between political terror and crime is that the former makes an open bid for public support. Unlike the criminal, the political terrorist is not easily deterred by punishment. Whatever we may think of their methods, terrorists have not only a need to be heard but, more often than not, a cause to champion.”[8] This is the reason why terrorists tend to get more energized whenever they are attacked, since they are for a cause. It is also the same reason they are ready to engage in suicide bombings.

The close connection between globalization and terrorism was stressed by the United Nations panel on Funding for Development on June 2001: “In the global village, someone else’s poverty very soon becomes one’s own problem: of lack of markets for one’s produce, illegal immigration, pollution, contagious disease, insecurity, fanaticism, terrorism”. [9] So it is evident that humanity is now much more interrelated because of challenges of poverty, migration, environmental crisis, pandemics such as HIV/AIDS, insecurity and global terrorism. Globalization considered as increasing interconnectedness brought about by trade, travel, technology, however has not been marched by a global ethic that entails a global criminal justice system, global economic policies, and global government.

The terror of globalization lies in the following contradictions: neighbors in the global village can live side by side with some swimming in affluence while others live on less than a dollar a day; neighbors living in security while others are constantly afraid of violent death; neighbors living in abundance of knowledge and skills, while others are living in ignorance. Peter Singer confronts this contradiction in the global village by suggesting that we need a new thinking about ethics beyond the nation-state model: “Implicit in the term of “globalization” rather than the older “internationalization” is the idea that we are moving beyond the era of growing ties between nations and are beginning to contemplate something beyond the existing conception of the nation-state.”[10]

What makes many doubt and question the logic of free market is what Yoshikazu Sakamoto noted as the inequality in the world system: “The present world order is characterized by the simultaneous presence of unprecedented levels of affluence and of poverty and hunger.”[11] What Sakamoto and many others who are critical of globalization is saying is the fact of over 800 million people suffering from hunger and malnutrition. In case one is tempted to argue that such glaring inequality and large scale hunger cannot be blamed on globalization and indifference Sakamoto suggests the following thought experiment: “If humankind lived in one country, with the richest top 10 percent of the total population residing in the Northern suburbs called OECD, while the bottom 10 percent lived in the Southern shanty towns on the brink of death from hunger, and the next 30-40 percent up poverty-stricken, this reality would be considered a political problem, drawing the attention of the public to the question of political accountability.”[12]

The extreme poverty that is tied to global inequality and even exploitative economic policies is a cause of much suffering worse than terrorism. Sakamoto goes further to call this form of suffering a genocide —“…the daily genocide of deprived people and infant children in the South.”[13] To this suffering add deaths from preventable diseases, armed conflict and displacement, and illiteracy. While humanitarian help and other forms of aid are usually poured to the South to alleviate suffering, the issue however is to put in place policies and political arrangement that will provide long-term solutions.

Without corresponding global government to control the global economy, there is a danger of further weakening of the nation-state, and increasing marginalization of poor sections of society. Global economy institutions such as World Bank, IMF, WTO cannot fill in the gaps for a global policy body, since they will most likely serve economic interests of the powerful actors in the world economic system. This partly explains why developing countries have been subjected to inconsistent and contradictory economic policies that were later deemed unviable. The main criticism leveled against the current form of globalization led by the Washington Consensus under the World Bank, IMF and WTO rubrics, is that it has tended to put profit above people’s wellbeing. Consequently, the environment has suffered under the tyranny of the free market. This model has also praised economic growth but ignored human development.

Just as the unregulated global economy has brought about great suffering across the world due to income inequality and exploitation of cheap labor, global terror has spread untold suffering across the world attacking centers of global capitalism. And since the world is very much interconnected, the terror attacks in one part of the world are felt across the globe. The global media quickly transmits images of horrific acts of terrorism, while terrorists use easy means of travel and communication to coordinate their terror attacks. The rise of terrorism has been linked to the three pillars of global governance (political pillar—states, international organizations; economic pillar—market, transnational corporations, private international organizations; Socio-cultural pillar—civil society and international non-governmental organization) deficiencies:

“Arguably, contemporary terrorism and the other anti-systemic forces created by globalization are symptomatic of the institutional deficiencies within all three governance domains and not likely to yield to traditional power structures of twentieth century international relations (no matter how much firepower the United States has and can project).”[14]

While the cold-war produced the “bi-polar” world (Western Block against Eastern Block), and the post-cold war engendered the “uni-polar” world with the US as the undisputed superpower, the 21st Century is confronted by a “tri-polar” world where power is shared among states, markets, and civil society or non-state actors. Although terrorist groups are not civil in their actions, they can structurally fit in the civil society domain since they operate outside the state-sphere.

COMMODIFICATION OF VIOLENCE AND VIOLENCE OF COMMODITIES

War or organized violence is an immensely lucrative business. Of all items on sell in the global economy none generates greater income than weapons ranging from guns to jet fighters. Arms factories employ people with specialized skills. There is more to war than meets the eye. Terrorism has also become a huge business empire. Below are some figures:[15]

- In 2013 Kenya allocated $846 million for security expenditure

- By 2012 al-Shabab used to collect about $25 million fees from Kisimayu port

- Al-Shabab is believed to have benefitted from the annual $53 million piracy booty

- The European Union Naval Force Somalia budget since 2010 totaled $54 million

- The 600-acre US Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti has a $1.2 billion budget for the next 25 years

- France and Japan pay $41 million each to Djibouti for the lease of their respective bases

And this is only in the Horn of Africa. Imagine what goes on in the Sahel region, the Great Lakes region and Nigeria with Boko Haram. With the recent attack on Paris, mention was made of the smuggling of illegal arms across Belgium that terrorists can access with ease.

Not only has violence been commodified but commodities are also used for violence. More than ever before has technology been used to manufacture sophisticated tools of violence. Destructive power on an unprecedented scale is possible thanks to “… the technology of destruction represented by the nuclear and high-tech weapons systems, which have the potential to annihilate human species many times over.”[16] Both terrorists and sovereign states have in their hands lethal weapons of mass destruction and it is not clear who should point a finger to the other. With increasing innovations in ICT, it is not inconceivable to imagine cyber warfare replacing the much feared nuclear war.

WAR ON TERROR AND TERROR OF WAR

After the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers in New York, the Bush Administration declared a war on terror. Shortly after, the US launched attacks on Afghanistan where Al-Qaeda had its base. The other country on the US hit list was Iraq where Saddam Hussein was believed to have weapons of mass destruction. This US declaration of war on terror brought to the fore a crucial debate on unilateralism and multilateralism. George Bush’s famous phrase: “You are either with us or against us” became a household phrase. Other developments came along this “declaration of war on terror” such as: legitimate means to extract information from terror suspects; individual liberties such as privacy (whether the state security should tap phone conversations); tight border controls and excessive search at airports; whether political activism can be classified as terrorism; and many others. Clearly the war on terror did increase terror all over the world as fear and insecurity got magnified, and the Bush Administration tackled the ‘axis of evil.’

Commenting on the post-9/11 Bush Administration’s war on terror, Mary Kaldor had the following to say: “Essentially the attacks on September 11 legitimized a new global unilateralism and military activism, a reversion to the reflexes of the centralized war-making state, a way of renewing governmental support when earlier national bargains were breaking down.”[17] With the war on terror, humanity is once again faced with the terror of war in countries such as Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Afghanistan, Mali, and Nigeria. With the war on terror civil society groups have embarked on campaigns for human rights, humanitarianism and international criminal justice system amidst gross violations of human rights and crimes against humanity. Global civil society suggests some alternatives to war that are worth considering. Among them are:[18] supporting local political constituencies to bring about regime change in case of criminal or illegitimate leaders; strengthening international humanitarian law; enhancing capacity for multilateral international law enforcement; commitment to global social justice.

If the war on terror succeeds in stimulating more terror attacks turning terrorists into heroes, but also hampering individual liberties seriously, then the war on terror would have been lost. Might there be other long term institutional options other than war? There is yet another ethical issue of just war theory. For a war to be considered just there are some conditions inter alia: 1) War should be tried after all other means have failed or war as a last resort; 2) The means used should not cause more harm than the good intended—principle of proportionality; 3) There should be reasonable hope of success. It is not clear whether the war on terror meets these criteria.

COSMOPOLITICS: TOWARDS A NEW GLOBAL POLITICAL ECONOMY AMIDST TERROR

A quick glance at the state democracy within states indicates that the process of democratization suffers from serious contradictions. There is increasing decline in the percentage of people who show up to vote even among developed nations. This raises the question of legitimacy of those in power and the policies they make. Mention was also made about the increasing power of non-state actors (NGOs, corporations, civil society organizations) who do not even vote. But the greater challenge facing democracy is at the global level or in the international system. This is why some scholars are now beginning to think of other movements that can influence policies in the area of environment, security, human rights and social justice. As Daniele Archibugi the leading architect of cosmopolitics has indicated: “…something more than internal democracy is called for if we are to attempt to solve the social, political and environmental problems facing the world. What is needed is the democratization of the international community, a process joining together states with different traditions, at varying stages of development.”[19]

Cosmopolitical democracy does not aim at destroying sovereign states, but rather increasing democratic space, such that democracy can be exercised within the state, among states and at the world level.[20] The main principle here is participation at all levels, that makes democratic processes thick, without leaving a vacuum anywhere. The assumption behind this cosmopolitical democracy is that terrorism is born of frustration with the world system the marginalizes and excludes people in the periphery both socially and epistemologically.

There is a lesson from the European Union. EU was formed for the following main reasons:[21] 1) To prevent the wars that had devastated Europe especially during the two world wars; 2) To strengthen Europe within the international context; 3) To prevent the expansion of the communist system toward Western Europe. Some questions need to be posed: Not only Europe was affected by the two world wars, so why not work out a world system that would prevent wars in the entire world? Why strengthen Europe alone within the international system instead of strengthening the whole international system? The prevention of the expansion of the communist system toward Western Europe is clearly what gave rise to the cold-war and its proxy wars across the globe including Africa. It is clear that the quest for continental interests as opposed to global interests is what has generated tension in the world order and given rise to superpower rivalry. While one is designing strategies to protect one’s interests, others are scheming along the same lines.

The world has faced horrendous wars and genocides and now is faced with terrorism. With increasing globalization it is increasingly clear that security threat in one country or region is a security threat to other countries or regions. Extreme poverty and deprivation in one part of the world creates favorable conditions for radicalization of poor and marginalized youth, as well as fertile ground for training extremist groups. A new international political economy is timely. No need to invent the wheel since there are some models to emulate. The League of Nations gave rise to the United Nations system as a strategy to coordinate international interventions for peace and progress of the entire world. Regional blocks such as the African Union (AU) and the Eastern African Community, just like the EU demonstrate that working together is much better than working in isolation. Why not take this regional integration and international system models to a higher level?

The EU follows what is called “functional federalism” whereby “…sovereign democratic regimes progressively cede authority over certain spheres of governance to a higher instance.”[22] This means that respective leaders and citizens of nation-states need to be aware that sovereignty is not an absolute value. Setting up a common market that allows free movement of goods, services, capital and labor, provides greater benefits to a country that subjects itself to a regional integration policy framework. Finally, a common currency can be agreed upon. If this arrangement can be done at a continental level, why not at a global level?

A question might be raised that the globe is too vast. But there is also the principle of subsidiarity, whereby the higher authority can only intervene when an issue cannot be resolved at a lower level. Other issues usually raised to challenge such a global governance model is that countries vary in terms of culture and economic development. But this argument can also be raised at the national level where there is never a uniform culture and same level of economic development among different parts of the country.

For such an international political economy to succeed it requires an economic philosophy or model. Since the neoliberal model has not worked for the good of all, and communism or state-controlled model has also failed, better to try to a middle ground, the social market economy. This is a hybrid model that combines elements of free market but also some form of state intervention to ensure that neither the big corporations nor the government exert too much dominance over the citizens. This is because both excessive centralized economic planning and excessive liberalism are detrimental to sustainable development. This is again to stress that neither individual liberties nor state-sovereignty are absolute values.

If global challenges such as climate change, terrorism, extreme poverty and state-failure are to be addressed with timely and long term solutions, there is need for a global governance framework akin to the European Union model. But for this to succeed, individual states must sacrifice some of their national interests for the greater global common good.

How will the new global governance architecture or cosmopolitics look like? It will constitute of two forms of integration: vertical and horizontal. At the horizontal level in keeping with the principle of subsidiarity, it will include segments of civil society that include faith-based organizations, cultural institutions, NGOs that work with local communities. At the political level, sub-regional groups such as SADC, EAC, and ECOWAS will also work to create horizontal linkages among states that have relatively equal levels of economic growth. But these respective countries will need to harmonize their electoral, democratic and economic policies.

At the vertical level, there are two layers of integration: at the continental level and at the global level. Here individual states will subject themselves to higher global rules and policies thus cede part of their national sovereignty for the greater global common good, so as to collectively address global challenges such as terrorism, poverty, ecological crises and sate-fragility. At this level global civil society organizations that operate across countries would also take part in policy formulation and norm setting though some form of representation, depending on their constituency and institutional capacity.

CONCLUSION

Global terrorism as the recent attacks on Paris have demonstrated is a great challenge that sovereign states have to deal with, and yet no single nation state is able to solve the issue of terrorism. The first step in addressing terrorism is to know its nature and dynamics. Secondly, it is to situate the discussion on terrorism in the broader context of globalization and international political economy. Third, it is to locate the discussion on terrorism in the framework of power and its dynamics. Moreover there is a new conception of power as seduction, known as “soft power.”

The concept of cosmopolitical democracy helps us to think beyond the sovereign state as the main actor in international relations given the new forces of globalization. If more actors can be included in shaping world events by contributing to policy formulation at the global level, this can go a long way to alleviate the impulse to use violence, as extremist groups are doing.

Faced with the challenge of terrorism some scholars have come up with an alternative vision called “democratic transnationalism” that “…attempts to draw on the successes of democratic, particularly multinational democratic, domestic orders as a model for achieving human security in the international sphere.”[23] Democratic transnationalism does not claim to re-event the wheel, since the principles that it takes at the global level have been around for decades: human rights, rule of law, and representative participation. The proposed Global Parliamentary Assembly (GPA) does not seem far- fetched since the UN General Assembly in fact looks like a world executive body, since it is comprised of heads of state. Why not create a global parliament with representatives elected from the respective countries using the principle of universal adult suffrage but not tied to a particular political party? This is to help end what many consider as exclusive membership clubs of UN agencies such as IMF, World Bank, and WTO.

*Odomaro Mubangizi (PhD) teaches philosophy and theology at the Institute of Philosophy and Theology in Addis Ababa where he is also Dean of the Department of Philosophy.

[1] Joseph Nye, JR., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2003), x.

[2] Ibid., xi.

[3] Hanna Arendt, On Violence (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. 1969), 10-11.

[4] Baffour Ankomah “How Africa Can Beat Terrorism” in New African, June 2014, 7.

[5] Yoshikazu Sakamoto, “Democratization, Social Movements and World Order” in Björn Hetten, International Political Economy (London: Zed Books, 1995), 131.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Interview with Fr. Thomas Michel, S.J. Secretary of Interreligious Dialogue” in Chiedza Journal of Arrupe College, Vol. 1, No. 1, April, 1998, 57.

[8] Mahmood Mamdani, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the cold War, and the Roots of Terror (Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 2004), 229.

[9] Quoted in Peter Singer, One World: The Ethics of Globalization (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003)

[10] Ibid., 8.

[11] Sakamoto, Op. cit., 134.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] James P. Muldoon, Jr., The Architecture of Global Governance: An Introduction to the Study of International Organizations (Oxford: Westview Press, 2004), 272.

[15] Wanjohi Kabukuru “The Business of Terrorism” in New African, June 2014, 24-25.

[16] Sakamoto, Op. cit., 131-132.

[17] Mary Kaldor, Global Civil Society: An Answer to War (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2003), 150.

[18] Ibid. 156-158.

[19] Daniele Archibugi, “Cosmopolitical Democracy” in Daniel Arhibugi et al, Debating Cosmopolitics (London: Verso, 2003). 7.

[20] Ibid., 8.

[21] Alfons Calderón and Luis Sols “Europe at the Crossroads” CJ Booklet, 153, 2014, 13.

[22] Ibid. 18.

[23] Richard Falk and Andrew Strauss, “The Deeper Challenges of Global Terrorism: A Democratizing Response” in Archibugi et al., Op. Cit., 203.