A Century-Old Crime Against Humanity – OpEd

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Mackubin Thomas Owens*

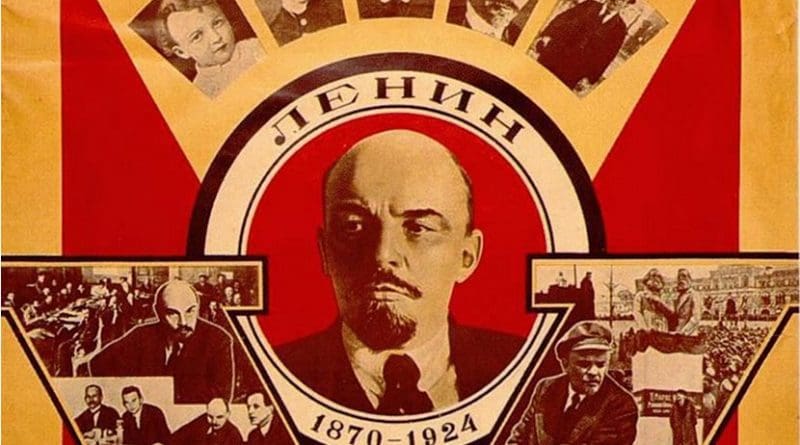

(FPRI) — The October Revolution of 1917 unleashed a century of evil, a virus that has claimed an unprecedented human toll. It is hard to comprehend the number of its victims, enslaved, oppressed, and killed in the name of a malignant ideology. Let us tally up the body count: 20 million deaths in the Soviet Union; 65 million in China; 2 million in Cambodia; one million each in Eastern Europe and Vietnam; 2 million each in North Korea and across Africa; 1.5 million in Afghanistan; and 150,000 in Latin America.

Not to diminish the unconscionable crimes of the Nazis, but it is a fact that communism has killed far more people than fascism ever did. Yet, although we are never hesitant to describe fascism and Nazism as “evil,” we often refuse to do so when it comes to communist regimes. The exception was Ronald Reagan when he described the Soviet Union as the “evil empire,” but I well remember the almost universal horror that greeted his pronouncement.

What explains this phenomenon? Why does communism get a pass that fascism never does? What accounts for the popularity of socialism among young people, who have flocked to the banner of Bernie Sanders during the primaries, or who march under the “antifa” flag?

This failure to denounce such a monstrous ideology is the result of a lack of education about communism, or even worse, mis-education. There are courses aplenty on college campuses about the Cold War and the Soviet Union. But, while historical treatments of Hitler’s Germany do not shrink from a moral judgement about Nazism, the same does not hold true concerning communist regimes. Too often, the Cold War is treated as a confrontation by two morally equivalent superpowers.

It seems to be the case that there are two main reasons for this mindset. The first is the willingness of many in the academy to accept the false, utopian promises of communism in the abstract as being morally superior to the mundane reality of capitalism. In the abstract, communism promises true equality. All that must be done is to abolish private property; social classes will disappear, and the state will wither away, the result of which will be Heaven on earth.

In the abstract, a communist society is, unlike Nazism, open to all. Distinct from the latter, the appeal of communism, at least in theory, is not self-limiting. Jews or Slavs cannot be true Nazis, but Jews and Slavs can be communists. Of course, the problem in practice is that human beings are recalcitrant. If they do not see the virtues of abolishing private property and the family, they must be “reeducated,” and if that doesn’t work, killed. This accounts for the vast body count of communism. Nazis only have to exterminate non-Aryans.

Communists must eliminate everyone who does not accept their ideology. Of course, the reality is far different than the promise, although it does lead to a sort of equality: equal misery for all. Except if one is part of the nomenklatura or the communist elite.

But once again, communism seems to get credit for its promises. As a Stalinist once remarked to George Orwell, if one is to make an omelet, one must be prepared to break a few eggs. Of course as the history of Soviet Russia, Communist China, Cambodia, and Cuba has shown, it is far more than a few eggs. And Orwell replied to the Stalinist, “Where’s the omelet?”

The second obstacle to teaching about the costs of communism is the triumph of cultural Marxism on college campuses. We were too quick to claim victory not only over the Soviet Union but also over communism itself, as pre-presented in Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History.” But, as Harry Jaffa observed in a 1991 lecture,

The defeat of communism in the USSR and its satellite empires by no means assures its defeat in the world. Indeed, the release of the West from its conflict with the East emancipates utopian communism at home from the suspicion of it affinity with an external enemy. The struggle for the preservation of western civilization has entered a new—and perhaps far more deadly and dangerous—phase.

Of course, the rot had begun long before. As Michael Walsh observes in his splendid book, The Devil’s Pleasure Palace: The Cult of Critical Theory and the Subversion of the West, it began with a group of intellectuals, including Herbert Marcuse, he of “repressive tolerance,” sociologists Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, and “sex therapist” Wilhelm Reich, all members of the “Frankfurt School,” the Institute for Social Research, who sought refuge in America from Nazi Germany. But once ensconced in the American academy, the Frankfurt boys proved to be the sort of parasite that eventually kills its host.

These “cultural Marxists” recognized that Marx’s target, the working class, would never buy into their argument. Communism had always been imposed by force. So instead, the Frankfurt boys exploited American intellectuals, who had always exhibited a sense of inferiority relative to Europe. This was indeed fertile ground, making it easy for them to effect the “long march through the institutions,” most importantly the academy. The Frankfurt boys understood that revolutionaries would be able to complete the seizure of political power only after achieving “cultural hegemony” or control of society’s intellectual life by cultural means alone.

As George Orwell observed, “there are some ideas so absurd that only an intellectual could believe them.” So it was with the Frankford boys’ overly intellectualized and emotionally juvenile approach to the world, the pernicious and reactionary philosophy of Critical Theory, which has unleashed a swarm of demons onto the American psyche.

Walsh argues persuasively that Marcuse and his ilk sought nothing less than the overthrow of both the moral and political orders of the West. Their ideology demanded, for philosophical reasons, a relentless assault on Western principles, including Christianity, the family, conventional sexual morality, and nationalist patriotism, which the Frankfurt boys saw as roadblocks on the path to revolution.

We now live in the world created by the Frankfurt boys and their followers. What they have wrought is not so much a defense of communism as the undermining of a moral defense of the West and liberal—in the proper sense—society. The West—and the United States, in particular—is morally tainted by racism, imperialism, and colonialism. The United States was founded by slave holders. How can it claim moral superiority over communism, which seeks to end racism, imperialism, and colonialism?

Certainly, those who make this argument ignore the fact that when the United States declared its independence in 1776, slavery was a worldwide phenomenon. But slavery was only part of a greater political reality. Before the American founding, all regimes were based on the principle of interest—the interest of the stronger. That principle was articulated by the Greek historian Thucydides: “Questions of justice arise only between equals. As for the rest, the strong do what they will. The weak suffer what they must.”

The United States was founded on different principles—justice and equality. No longer would it be the foundation of political government that some men were born “with saddles on their backs” to be ridden by others born “booted and spurred.” In other words, “equality” means that no one had the right to rule over another without the latter’s consent.

Slavery, of course, was a violation of this principle, but as Jaffa, has written: “It is not wonderful that a nation of slave-holders, upon achieving independence, failed to abolish slavery. What is wonderful, indeed miraculous, is that a nation of slave-holders founded a new nation on the proposition that ‘all men are created equal,’ making the abolition of slavery a moral and political necessity.”

The United States transcended its original flaw. Not so with communism. As the British novelist, Martin Amis recently wrote of communism in a piece for The New York Times Book Review marking the October Revolution,

It was not a good idea that somehow went wrong or withered away. It was a very bad idea from the outset, and one forced into life—or the life of the undead—with barely imaginable self-righteousness, pedantry, dynamism, and horror. The chief demerit of the Marxist program was its point-by-point defiance of human nature. Bolshevik leaders subliminally grasped the contradictions almost at once; and their rankly Procrustean answer was to leave the program untouched and change human nature.

In the end, we must deploy three weapons in order to ensure that rising generations understand the truly evil nature of this odious ideology: Education, Education, Education. FPRI continues its role in educating people about this odious ideology. But much more needs to be accomplished.

About the author:

*Mackubin (Mac) T. Owens is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and editor of Orbis, FPRI’s quarterly journal. He is also Dean of Academic Affairs and Professor at the Institute of World Politics in Washington, D.C.

Source:

This article was published by FPRIThe above E-Note is a part of the Editor’s Corner in the Winter 2018 edition of Orbis: FPRI’s Journal of World Affairs..

You failed to mention how many people capitalism has murdered and enslaved in the last century or so.

Capitalism is not perfect, and needs sensible government control, but it is a product of freedom! Far less have been murdered than can be attributed to communism!