Vernacularization And Linguistic Democratization – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

The use of a language in written and formal contexts that is distinct from the languages used in everyday communication – such as Latin in early modern Europe and Standard Arabic in the Arabic-speaking world, both past and present – comes with benefits, but also with costs. Drawing on publishing data from early modern Europe, this column shows that the Protestant Reformation led to a sudden and sharp rise in vernacular printing, such that by the end of the 16th century, the majority of works were printed in spoken tongues rather than in Latin. This transformation allowed broader segments of society to access knowledge. It also diversified the composition of authors and book content and had long-term consequences for economic development.

By Christine Binzel, Andreas Link and Rajesh Ramachandran*

A disconnect between the language used in written and formal contexts – for example in the domains of public administration, education, law, and politics – and the varieties of language spoken on a day-to-day basis has been a feature of many states, both past and present. These varieties of language, or vernaculars, often remain oral tongues whose standardisation is incomplete.

By contrast, knowledge of the language used in written and formal contexts typically remains restricted to elites. In many cases, this formal language eases understanding across a large geographic area with numerous vernaculars and is no longer used for everyday spoken communication (Burke 2004, Pollock 2006, Versteegh 2014).

Our paper (Binzel et al. 2020) first provides a conceptual framework to explain why such a linguistic situation, commonly referred to as diglossia (Ferguson 1959, Versteegh 2014), has been a stable hallmark of many societies over extended periods of time (often centuries). This is despite the costs it potentially generates for non-elites and for society in general when it comes to communication, knowledge acquisition and production, and political engagement.

In light of these costs, we identify three types of barriers – economic, social, and political – to vernacularisation, that is, to the increased use of common tongues in writing. We then empirically study perhaps the most important historical event that promoted the use of the vernacular – the Protestant Reformation of 1517.

Martin Luther, whose Ninety-five Theses mark the beginning of the Reformation, deliberately chose to write many of his pamphlets and books in German rather than in Latin, and he translated the Bible into German in 1522 (Graf 1991, Edwards 2004). By using a well-understood language, Luther and his followers aimed to reach the widest possible audience. He also wanted lay people to be able to understand and engage with the Bible (Burke 2004).

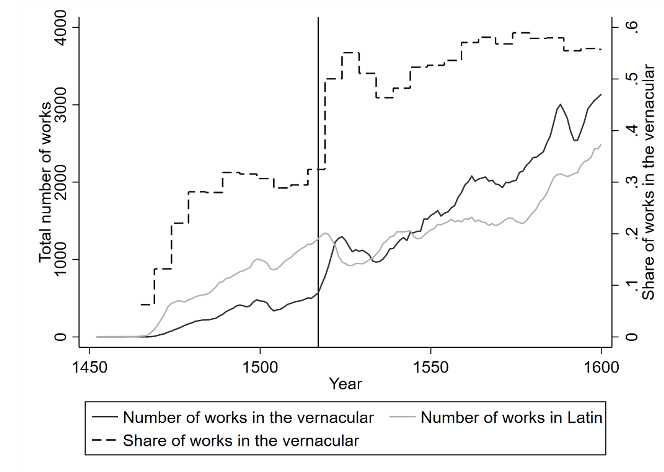

Drawing on data from the Universal Short Title Catalogue on all books and pamphlets printed in Europe between 1451 and 1600, Figure 1 shows that the number of works printed in vernaculars surpassed the number of works printed in Latin by the end of the 16th century. Furthermore, there was a sharp increase in the production of vernacular works at the time of the Protestant Reformation. Given the general population’s inability to speak or write in Latin, this switch to the vernaculars allowed broader segments of society to access knowledge.1

Figure 1 Total number of works (books and pamphlets) printed in Europe

The sudden and substantial increase in the production of vernacular texts following the Reformation allows us to empirically test the validity and consequences of our conceptual framework. To this end, we create a city-level panel combining the Universal Short Title Catalogue with available city-level data. We then compare outcomes across printing cities that had adopted Protestantism by 1600 (“eventually Protestant cities”) and those that remained Catholic, similar in spirit to Cantoni et al. (2018).2

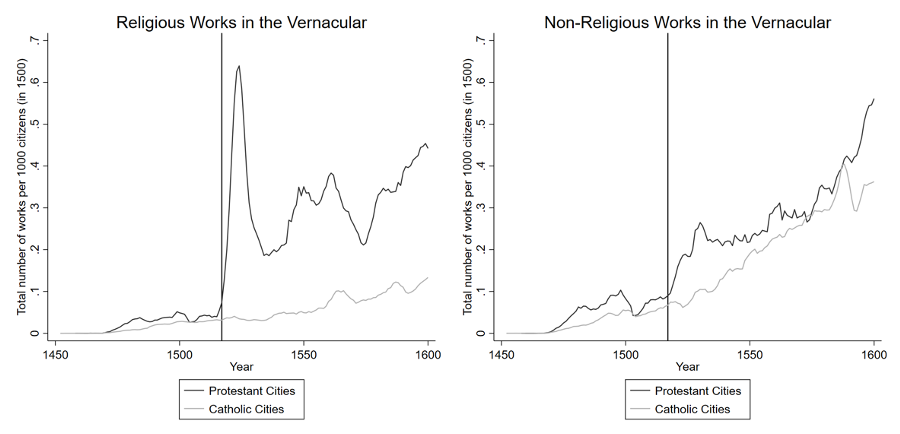

Figure 2 plots the total number of religious and non-religious vernacular works in a city averaged across Catholic and eventually Protestant cities. While eventually Protestant and Catholic cities have similar trends (even levels) in the production of vernacular texts prior to the Reformation, there is a dramatic surge in religious vernacular printing output immediately after the Reformation in eventually Protestant cities (left panel). Soon after, non-religious vernacular works are printed in increasing numbers in both Protestant and Catholic cities (right panel), consistent with the idea that the reformers, by using the vernacular in their writing, reduced the various barriers to vernacularisation.

Figure 2 Religious and non-religious vernacular works over time: Eventually Protestant vs Catholic cities

Economic and political barriers to vernacularisation

We next show that the Reformation indeed helped reduce the economic and political barriers to vernacularisation. We first look at German-speaking cities that became Protestant by 1600. We show that cities with a dialect similar to the one spoken in Wittenberg, the city where Luther lived and worked, experienced larger increases in vernacular printing output after the Reformation as compared to those with a dialect distinct from the one spoken in Wittenberg. This provides evidence for significant economic costs associated with using the vernaculars in writing.

We then examine potential political barriers to vernacularisation. We restrict our sample to cities located in the Holy Roman Empire and compare Catholic cities that are in the vicinity of a Protestant city (cities with high competition in the market for religion) with Catholic cities that are located further away (low-competition cities), similar to Cantoni et al. (2018).2

Our estimates indicate that Catholic cities that faced more competition in the market for religion experienced a stronger increase in vernacular printing output immediately after the Reformation as compared to Catholic cities that faced low competition in the market for religion, thereby providing evidence for the importance of political barriers.

Consequences of the increased use of the common tongues in writing: Linguistic democratisation

The sudden and substantial increase in the production of vernacular texts following the Reformation also allows us to empirically examine the immediate consequences for knowledge creation. To this end, we collect background information on well-publishing authors in the Universal Short Title Catalogue. We classify authors as coming from a high socioeconomic background if their family was noble or likely literate in Latin; all other authors are considered as coming from a low socioeconomic background. Using this definition, 71% of authors have a high socioeconomic background.

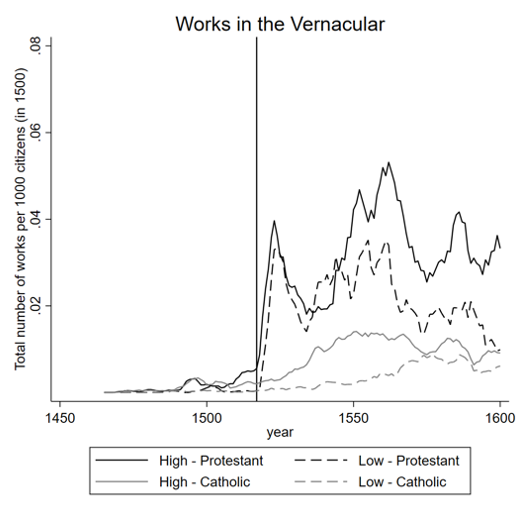

Figure 3 plots, separately for works in the vernacular and in Latin and for eventually Protestant and Catholic cities, the total number of works in a city averaged across authors with a high and a low socioeconomic background. Before the Reformation, few titles appeared in the vernacular, and nearly all were from authors with a high socioeconomic background. This was the case in both Protestant and Catholic cities.

Immediately after the Reformation, we see a sharp rise in the number of titles in Protestant cities, with equal distribution between authors from the upper and lower social strata. In Catholic cities, vernacular printing output only increased with some lag and less strongly after the Reformation. Moreover, only after 1550 did Catholic cities experience an increase in works from authors with a low socioeconomic background.

Figure 3 Vernacular works over time: Authors with a low vs a high socioeconomic background in eventually Protestant vs Catholic cities

We furthermore document that following the Reformation, there was a differential increase in a city’s number of Universal Short Title Catalogue subject classifications, suggesting that book content became more diverse.3

Vernacularisation and longer-term development

Lastly, we turn to longer-run trends. If vernacularisation allows larger segments of society to participate in knowledge production and consumption and in social life more generally, we should observe that cities with higher vernacular printing output experienced greater economic growth.

Consistent with this idea, we find that vernacular (but not Latin) printing output is associated with future city population growth, a proxy for economic development in this era. Also, cities’ (non-religious) vernacular printing output is positively correlated with future births of famous individuals, a proxy for upper-tail human capital (Schich et al. 2014, Serafinelli and Tabellini 2017), both in the cross-section and in a panel of cities over six 30-year periods. In this way, we argue that the vernacularisation of printing was an important driver of European dynamism in the early modern period.

Implications

In how far are our findings generalisable to other contexts? It is difficult to assess the potential costs of diglossia in the Arabic-speaking world, for example, given that Arabic diglossia continues to exist (Versteegh 2014). Similar to Latin, Standard Arabic may have acted as a barrier to knowledge production and consumption (Maamouri 1998). This would be consistent with the fact that book production has remained low4 and that the Arabic-speaking world scores low in terms of technological innovation (UNDP 2003, WIPO 2016). However, further research is necessary to better understand the role of diglossia for contemporary economic development.

*About the authors:

- Christine Binzel, Professor of Economics: Economy and Society of the Middle East, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg; CEPR Research Affiliate

- Andreas Link, PhD candidate, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg

- Rajesh Ramachandran, Postdoctoral Researcher, Heidelberg University

References

Binzel, C, A Link and R Ramachandran (2020), “Vernacularization and linguistic democratization”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15454.

Burke, P (2004), Languages and communities in early modern Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cantoni, D, J Dittmar and N Yuchtman (2018), “Religious competition and reallocation: The political economy of secularization in the Protestant Reformation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(4): 2037–96.

Edwards, M U, Jr (2004), Printing, propaganda, and Martin Luther, Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Ferguson, C A (1959), “Diglossia”, Word 15(2): 325–40.

Graf, H J (1991), The legacies of literacy: Continuities and contradictions in Western culture and society, Volume 598, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Maamouri, M (1998), “Language education and human development: Arabic diglossia and its impact on the quality of education in the Arab region”, ERIC.

Pollock, S (2006), The language of the gods in the world of men: Sanskrit, culture, and power in premodern India, Oakland: University of California Press.

Schich, Maximilian, Chaoming Song, Yong-Yeol Ahn, Alexander Mirsky, Mauro Martino, Albert-László Barabási and Dirk Helbing (2014), “A network framework of cultural history”, Science 345(6196): 558–62.

Serafinelli, M, and G Tabellini (2017), “Creativity over time and space”, IGIER Working Papers 608, Bocconi University.

The Economist (2016), “Arabic publishing: Plus de kutub, please”, 16 June.

United Nations Development Programme (2003), “Arab human development report 2003: Building a knowledge society”.

Versteegh, K (2014), The Arabic language, 2nd edition, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

World Intellectual Property Organization (2016), Intellectual property statistics database.

Endnotes

1 In our paper, we provide several pieces of evidence that literacy rates in the vernacular were substantially higher than literacy rates in Latin. The latter are estimated at 1% to 2% (http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/backgrounds/literacy/robert-a-houston-literacy).

2 For ease of presentation, this column shows the descriptive results. In the paper, we examine the effect of the Reformation more formally using a difference-in-differences approach. The difference-in-differences estimates confirm the pattern observed in the raw data.

3 The Universal Short Title Catalogue distinguishes 37 subject classifications in total, including art and architecture, economics, government and political theory, jurisprudence, literature, medical texts, music, and science.

4 Some estimates suggest that the entire Arab world produces fewer books than individual European countries, such as Belgium (The Economist 2016). Books in certain fields, such as economics, but also children’s books, are only available in Standard Arabic while foreign books are typically often sold in English or French rather than in Arabic (The Economist 2016).