Choreographing A Pas De Deux: A Dutch Perspective On NATO’s (And The EU’s) Near Future – Analysis

By Hugo Klijn*

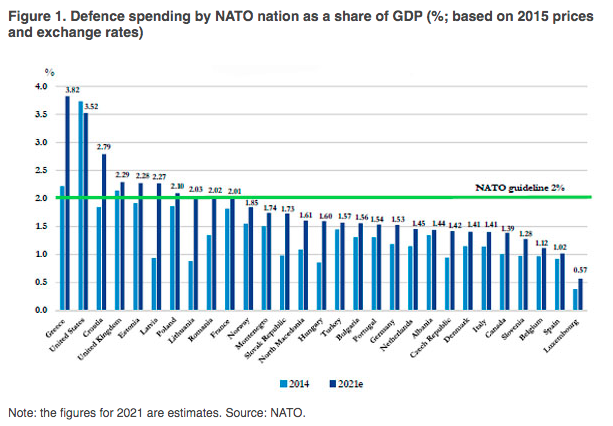

With regard to NATO, the Netherlands combines various capacities. As one of the Organisation’s founding members it has traditionally been considered a loyal ally. At some junctures it has also been a difficult member, for instance during the Euromissile crisis in the 1980s. Arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation remain priorities for the Netherlands, which participates in NATO’s nuclear sharing tasks with dual-capable fighter jets. The Netherlands is an EU père-fondateur too, and actively involved in shaping its own security and defence policy. At the same time, it is falling behind with its own commitments, reiterated at NATO’s Wales Summit in 2014, to spend more on defence. So what is The Hague’s view on the Alliance’s upcoming Madrid Summit, its new Strategy, the 2030 agenda and the future of transatlantic relations in a broader sense?

At the last NATO summit in June 2021 allied Heads of State and Government, alluding to an ‘increasingly complex’ external security environment, announced the opening of a ‘new chapter in transatlantic relations’. But political leaders may as well have been referring to the internal turbulence NATO underwent during the Trump Administration. This recent experience may explain why NATO 2030 –an agenda for the transatlantic future that was endorsed at the summit– was given a rather modest timeframe. The agenda comprises nine themes, including the adoption of a new Strategic Concept in 2022. The document will replace the 2010 edition and set the Alliance’s strategic political and military direction. The average lifespan of NATO Strategic Concepts is about 10 years, so the updated version will merge with the agenda’s trajectory.

How to label China?

For the Netherlands, NATO remains central to its security policy and it will subscribe to the general gist of most, if not all, of the proposals enumerated in NATO 2030. Among these issues the rise of China, which features as a NATO topic since late 2019, will no doubt be a tough nut to crack for the Alliance, with the US insisting on the military nature of Beijing’s ascendancy whereas others are still not convinced –or may fear this categorisation will be at the expense of other, more pressing concerns, like Russia and terrorism–. The Netherlands (aware of the EU’s elaborate definition of China as partner-competitor-rival) will likely opt for the middle ground, and propose that China be looked upon as an unconventional challenger that should also be dealt with in cooperation with other institutions, such as the EU. The security implications of China’s technological edge are also mentioned as a topic for NATO to address. In this regard, the Netherlands has recently joined 16 other allies to lead a new NATO innovation fund –the Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North-Atlantic (DIANA)–, although its initial budget of US$1 billion over a period of 15 years, as well as the absence of countries like the US and France, make for a rather modest start.

Breaking down a not-so-cooperative security

In the run-up to Madrid, however, the Netherlands will be more particularly interested in topics that fall under the rubrics of partnerships and cooperative security, with a special focus on NATO-EU synergies. This approach would correspond with the long-standing Dutch ambition to act as a bridge-builder between both organisations. NATO-EU cooperation may not be the most eye-catching topic to be discussed –Russia, China, cyber and space are more likely to compete for the headlines– but it is a theme deserving of further investments.

Cooperative security is currently the Alliance’s third ‘essential core task’, next to collective defence and crisis management. In the language of 2010, this task relates to developments beyond NATO’s borders that are to be addressed by forging partnerships with other countries and organisations and by contributing to arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation (ADN). The term ‘cooperative security’ was adopted by NATO at a fairly late stage (for instance, its 1999 Strategic Concept mentions it once, and only when describing the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, or OSCE), but clearly emerged in the context of the overall more optimistic security outlook of the earlier post-Cold War period. Today, with a renewed focus on deterrence and defence, cooperative security is a scarce commodity, and the implementation of this task has become less self-explanatory.

Looking at partnerships, apart from a host of bilateral arrangements, NATO has maintained frameworks such as the Euro-Atlantic Partnership, the Mediterranean Dialogue and the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative –not all of which are particularly lively venues–. A more recent addition concerns NATO’s four Indo-Pacific partners, Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea and New Zealand, who, with an eye on China’s growing prominence in the region, regularly consult with NATO on security matters. These partners seem hesitant, though, to formalise the partnership into a new council lest they provoke Beijing’s ire. Some European allies, too, will display caution in developing the relationship as long as the elaboration of NATO’s China policy is being discussed. The brusque announcement of a trilateral security pact outside NATO between Australia, the UK and the US (AUKUS) is bound to complicate this allied conversation.

Adding to this, the prospect of any breakthroughs in the field of ADN, another key component of cooperative security, looks grim. After the US and Russia walked out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, a new nuclear arms race seems underway that now includes China as well, while it is doubtful whether the upcoming review conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (scheduled for January 2022) will yield meaningful results. In the conventional arms sphere, the picture is no less discouraging, with the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty on life support since 2007, the US and Russia withdrawing from the Open Skies Treaty, and the latter routinely circumventing the political obligations under the OSCE Vienna Document’s transparency rules, eg, when conducting military exercises near NATO’s borders. In short, these circumstances do not bode well for NATO’s third core task, and one may wonder whether the Russian Federation, which certainly meets all criteria to remain the Alliance’s primary adversary in terms of collective defence, will feature at all in a ‘cooperative’ sense. Moscow has closed down its NATO mission and does not seem interested in any form of dialogue, other than the more prestigious bilateral ‘strategic stability’ talks with Washington. So, if the Netherlands wants to zero in on this domain, it can cross out several items and will, almost by default, have to concentrate on the enduring promise of NATO-EU cooperation.

Uneasy dancing with the stars

NATO and the EU have 21 overlapping memberships, but for many years these two Brussels-based organisations have been engaged in an often tedious process of attraction and repulsion. Of course, their mutual relationship is a complex matter since they represent different frameworks, while NATO’s non-EU members are significant players –think the US, Turkey and, since recently, the UK–. The concurrent EU-US relationship as a whole is not free of tensions either. At the same time, given the uncertainties under today’s geopolitical circumstances it still makes sense for NATO and the EU to step up their interactions. Judging by the bold language on NATO-EU cooperation in communiqués and joint declarations, there is no lack of verbal support in this regard.1 But for this relationship to become really meaningful it is required that, on the one hand, the US stop looking at European capacity building through the prism of its own defence industry and, on the other hand, Europeans put their money where their mouth is and show their determination to enhance their abilities to act more independently. With Washington turning its attention to Asia and Europe worrying about being left to its own devices, the case becomes even more compelling.

Dutch-German proposals

In May of this year, the Netherlands and Germany reportedly wrote a paper on this topic that was circulated among NATO and EU governments (and seems to have received broad support). Apparently, the authors argued in favor of streamlining both organisations’ ‘strategic review processes’: ahead of NATO’s new Strategic Concept, the EU will publish a Strategic Compass on security and defence in March 2022. In a general sense, the food-for-thought paper is said to have pleaded for more joint action, such as political consultations on a range of security topics, more joint statements, sharing intelligence and even organising joint travel by NATO and EU top officials. Such proposals, not all of which are entirely new, seem innocent enough for organisations that champion the same democratic values in the face of growing challenges from authoritarian actors. Still, a panel of experts who were asked by NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg to reflect on NATO’s future, including NATO-EU relations, cautioned against ‘developing new mechanisms to broaden the relationship’ and instead advised to ‘make fuller use of existing arrangements and identified areas of cooperation’. They even cited an earlier expert report from 2010, which had reached similar conclusions. This time around, would there be an impetus for NATO and the EU to pull themselves out of the swamp of unfulfilled ambitions?

The times they are a-changing

The transatlantic community is undergoing change in slow motion. It is in the nature of international relations, also within coalitions, to be dynamic. Even though NATO managed to reinvent itself as a crisis management tool, the end of the Cold War was always going to affect the Alliance. This change occurs through shocks (such as the Trump Administration) and structural developments (such as the rise of China) whose effects can be mutually reinforcing. During this transition phase, it is difficult for an established security actor like NATO and an aspiring security actor like the EU to determine their exact relationship, all the more so when the long-term commitments of the US to Europe’s defence are being questioned and European countries have ‘unlearned’ to take care of their own hard security business. It is a tall order to be dual-hatted as a NATO and an EU member and to have to square the circle of hedging one’s bets while remaining committed to US leadership in NATO. On top of that, European countries’ threat assessments vary, in that some primarily worry about Russia’s behaviour in the East and others are animated rather by instability and migration flows from the South. Some advocate ‘NATO first and foremost’, others tend to think more in terms of a division of labour.

For the time being, this conundrum does not allow for ‘either/or’ solutions, so there is no alternative but to carry on with steadily improving NATO-EU ties. In that context, the Netherlands is right to pursue this endeavour with like-minded partners, even if it concerns a ‘small step’ process and full complementarity is not on the cards. On a positive note, the EU’s External Action Service recently set up a task force on EU-NATO relations in order to strengthen the partnership. As the experts recommended, the most promising commonalities are probably to be found in concrete win-win areas such as capability planning, military mobility and coordinating climate and security policies –which are difficult enough–. This may be a more fruitful avenue than amplifying the joint agenda with ambiguous topics such as societal resilience, considered by some European allies as not necessarily belonging to NATO’s immediate writ, which therefore may yield but more controversy.

No representation without taxation

A major contribution European allies can make to improve NATO-EU relations, though, is to bring their defence spending in line with the 2% GDP benchmark they signed up to. Even if this is a crude and incomplete measure, living up to this commitment would empower these countries to take greater responsibility for their own security, irrespective of the exact evolution of the NATO-EU debate. There may be some irony in the fact that the Netherlands and Germany, the initiators of this renewed attempt at NATO-EU cooperation (who at the time of writing both happen to be forming new governments) stand shoulder to shoulder below NATO’s spending guideline (see figure). At the same time, their budgets have been on the rise since 2014 and the awareness that more is needed may be growing.2 New pledges will put them in an even better position to further the cause of pushing NATO and the EU in the same direction.

*About the author: Hugo Klijn, Senior research fellow at the Clingendael Institute for International Relations in the Hague | @HugoKlijn

Source: This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute

Disclaimer

The Elcano Royal Institute is launching a series of publications with the aim of feeding into the emerging debate around NATO’s Strategic Concept by providing a collective and national approach to the future of NATO. Selected national experts from different NATO allies (United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Netherlands, Italy and Portugal) have contributed to the series by portraying the current debate in their home countries around the Strategic Concept and the future of the Alliance. Thus, the Elcano Royal Institute seeks to highlight the importance of the renewal of the Concept and its adoption at the Madrid Summit, to be held in Madrid in June 2022.

1 See for instance the recent ‘post-AUKUS’ US-France joint statement at United States-France Joint Statement | Élysée (elysee.fr)

2 For the Netherlands see Defence Vision 2035 | Publication | Defensie.nl