Extensive Vs Intensive Farming – Analysis

The West’s battle against meat consumption poses environmental and social consequences for communities that rely on sustainable livestock production.

By Pablo Vidal-González and Joel Bueso*

Historically, meat consumption was for the rich. For generations, the majority of the population could afford to eat meat only a few days throughout the year.

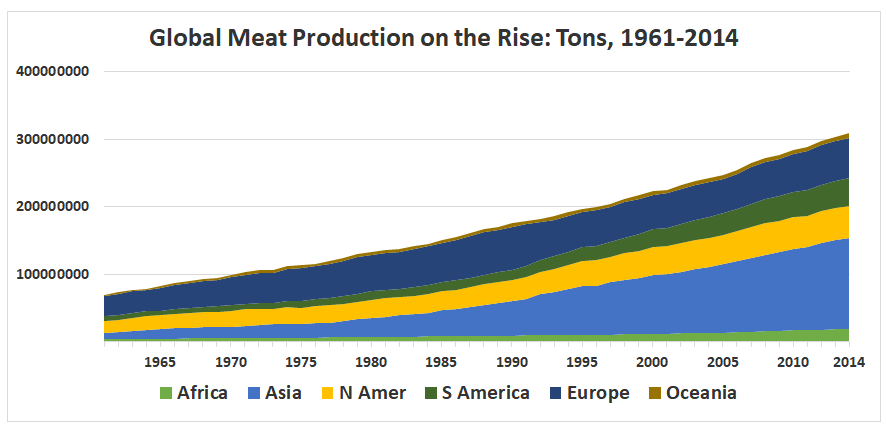

Throughout the 20th century, Western society associated welfare with high meat consumption, which led to causing major health problems, including cardiovascular disease and high cholesterol levels. In turn, developing countries are increasingly adapting urban and sedentary lifestyles. Although the consumption of meat continues to grow, mainly due to the growth of the middle class in China and Brazil, the welfare societies of Europe and North America have started a battle against the consumption of meat.

This battle likewise poses health, environmental and social consequences that could threaten entire communities that depend on sustainable production of livestock.

The United States and New Zealand are world leaders in meat consumption, exceeding 100 kilos per person per year. However, the number of vegan or vegetarian people is growing significantly in these Western countries, especially among young adults, despite evidence that moderate meat consumption improves health. Concerns about meat include worries about health issues and the environmental impacts of the intensive meat industry. Research has shown that intensive meat production has negative impacts from an environmental point of view, especially on large factory farms that do not properly treat waste, generating significant pollution. Recent images of huge cattle farms in the Amazon, created by burning the rainforest, have aggravated this controversy.

The polarization is severe between those who consume meat and those who do not. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, has released a report encouraging careful land management to feed a growing global population and public incentives to reduce meat consumption.

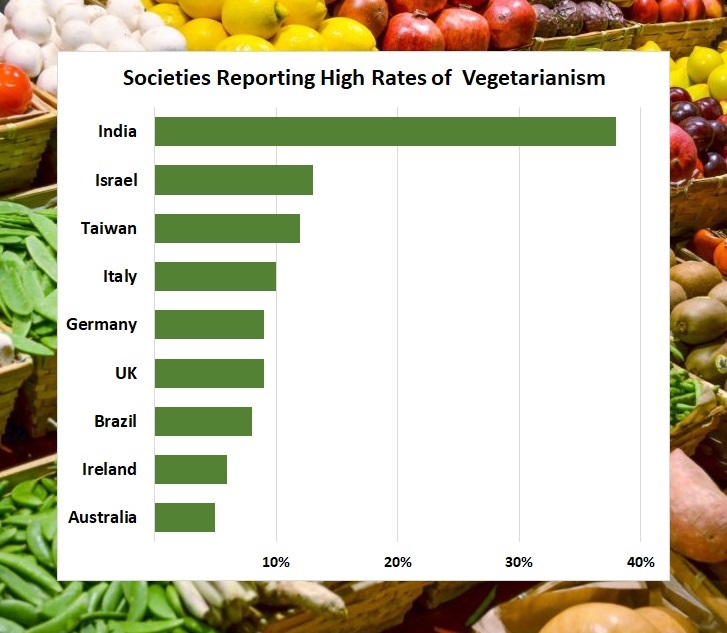

Yet, meat is a good source of energy and a range of essential nutrients, including proteins and micronutrients such as iron, zinc and vitamin B12. It is possible to obtain a sufficient intake of these nutrients without eating meat if a wide variety of other foods is available and consumed. However, access to alternative nutrient-dense foods may be limited in some low-income countries, and therefore, diets low in meat may have negative health impacts. Approximately 35 percent of people in India are vegetarians, and while the health impacts of vegetarianism are not well documented, some evidence suggests that Indian vegetarians have a slightly more favorable cardiovascular risk profile than that of non-vegetarians.

In high-income Western countries, large prospective studies and meta-analyses generally show that total mortality rates are modestly higher in participants who have high intakes of both red and processed meat than in those with low meat intakes, whereas no or moderate inverse associations have been observed for poultry consumption. Part of this may be due to the association of high meat intake with other major risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity and lack of exercise. More research is required to remove the statistical influence of such confounding factors.

Pasture feeding of livestock naturally enhances the proportion of long‐chain fatty acids in meat, often enriching the meat with antioxidants and enhancing quality when there are high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Pasture feeding has been demonstrated to offer positive impacts on the nutrient profile of milk, increasing beneficial nutrients such as omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vaccenic acid and conjugated linoleic acid, while reducing levels of omega-6 fatty acids and palmitic acid. The nutritional profile of “grass-fed” dairy cows resonates with consumers who desire healthy, “natural” and sustainable dairy products. Pastoral farming includes cattle, sheep, goats, pigs as well as goats, horses, ducks, camels, llama, reindeer, water buffalo, yaks, turkeys and more.

The debate should not be between consuming meat or not. Once again, as the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle pointed out, the solution is in the middle. The response lies in reasonable consumption of meat, mainly for health reasons and promoting responsible farming practices.

Livestock contribute 40 percent of overall agriculture value, supporting livelihoods of 1.3 billion people, reports the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and is among the fastest growing sectors in agriculture. Not all meat comes from intensive polluting livestock farms. It is estimated that there are between 50 million and 100 million nomadic or transhumant people in the world. These pastoralist people manage small herds, about 120 million animals in all, often moving with the seasons to survive. Often, such territories have no other use. So in this sense, failure to explain the advantages of a sustainable meat consumption and alternatives to factory farms could mean condemning nomadic peoples to abandon their territories and march on the big cities, deepening the serious challenges of inequality, poverty and more large-scale farms.

Such pastoral herding and other small agriculture operations are known as extensive livestock farming, characterized by low productivity per animal and use of surface. Such farms require less capital and resources. Extensive livestock farming is usually present in territories with low population density and extreme climates, where more intensive and productive agriculture is not possible, such as the Eastern region and the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. Such farming methods make it possible for human populations to remain in rugged rural areas. Pastoral farming offers environmental advantages, such as the cleaning and managing of forests and prevention of wildfires, and also ensures improved animal welfare by rearing animals in open and airy places.

Small farmers also confront pricing challenges. In Spain, the price of lamb has remained unchanged over the last 20 years, while production costs have risen in line with inflation. This is due to decreased consumer demand. Sheep are at the base of extensive rural livestock, and for 20 years, the number of heads has dropped dramatically.

Meat producers recognize the many challenges, and organizations like the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium in New Zealand fund research to improve feed and reduce environmental impacts.

Society, in a rush to tackle climate change and promote good health, cannot dismiss pastoral farming. There are tremendous benefits to diets that include moderate consumption of meat from animals raised in extensive regimes, respectful of nature and the rural milieu. Elimination of pastoral farming would pose many consequences, displacing up to 100 million people and abandoning large areas that are now alive and rationally exploited to desertification and oblivion.

*Pablo Vidal-González, a specialist on pastoralism and nomadic people, is a Social and Cultural Anthropology professor at Catholic University of Valencia, Spain, and visiting fellow at CLAIS-MacMillan Center, Yale University.

*Joel Bueso is a veterinarian and professor at Catholic University of Valencia, Spain. He is a specialist on extensive livestock health and local goat and sheep species.