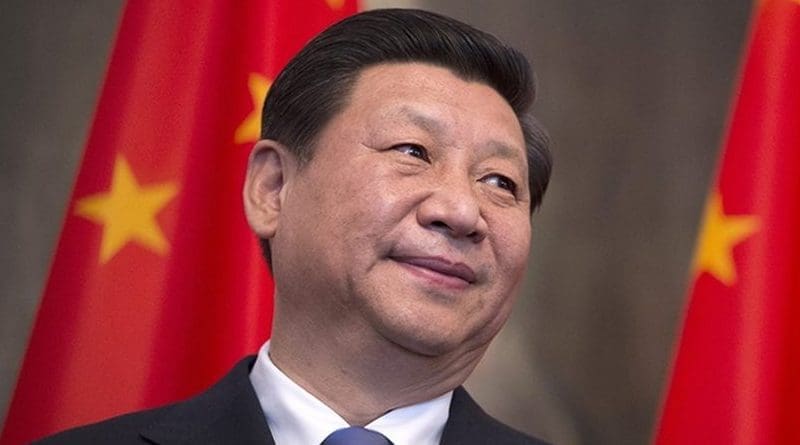

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Strategic Tibet Visit – OpEd

By IDN

By Shastri Ramachandaran *

The significance and strategic implications of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Tibet from July 21-23 is unlikely to be lost on those entrusted with India’s external affairs, national security and defence.

How New Delhi views this landmark visit to the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) by a Chinese president—the first since President Jiang Zemin’s visit in 1990—needs to be adequately articulated to enable an informed understanding of what it means in the context of the current impasse in eastern Ladakh between the armed forces of the two Asian giants.

Surprisingly, so far, there has been no studied response from the Government of India or the community of strategic affairs ‘experts’ who speak up for the establishment.

President Xi’s visit to the strategically important TAR was unannounced and kept secret until it had concluded. Whether this was out of consideration to the sensitivities of TAR, the region or the ‘international community’, or all three remains a matter of conjecture. The fact is that the visit has meaning and messages for all three.

Official reports said Xi’s visit—the first since he became president in 2013—was to mark the 70th anniversary of the “peaceful liberation of Tibet”. He had last visited Tibet in 2011, as vice president, for the 60th anniversary of Tibet’s “liberation”. He flew directly to Nyingchi, the border town close to India’s Arunachal Pradesh, and then to Lhasa by the bullet train operating since June 25.

Xi, who is also Chairman of the Central Military Commission, had a meeting with top military officials in Lhasa and troops stationed in Tibet. According to state-owned media, he exhorted the forces to “fully strengthen the work of training soldiers and war preparation” and “promote long-term stability and prosperity of Tibet”.

A cursory reading of Xi’s utterances on his visit to TAR suggest that his messaging is intended as much for Tibet and Tibetans as for India and the “international community”. His presence in and show of his ‘hold’ on Tibet is message enough for those preoccupied with the issue of the Dalai Lama’s successor and where s/he may be born. But there is more than that to his visit.

Although Beijing is in full political and military control of TAR, all the Tibetans are not entirely reconciled to this. Within TAR, Tibetans enjoy the fruits of economic and social development but feel the absence of both religious and political freedom. During a visit to Lhasa, I found that Tibetans from India had returned to TAR because, despite the absence of political freedoms, life and living conditions for them and their families were better in China. They found well-paying jobs, enjoyed a higher standard of living than say, for example, in India, had the benefits of social security, health care and good education and were generally secure.

While consoling themselves that they were fortunate to be in Tibet, they were deeply pained by the Dalai Lama being in exile from his land. What makes it worse is the absence of any space whatsoever to express this anguish over the absence of their God-King from the land of his birth; which keeps them acutely aware at all times of their lack of political freedom.

Many young Tibetans, who see “Free Tibet” as an elusive goal, have become realistic enough to pursue practical options for a better life, be it in TAR, elsewhere in China, India or the West. China’s success in “persuading” many young Tibetans to join the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) underscores the pragmatism of the recruits and their acceptance of a life choice that was unthinkable for Tibetans a few decades ago.

The conspicuous recruitment of Tibetans amidst heightened PLA activity on the other side of the 3488-km border from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh suggests a hardening of Beijing’s political and military stand. Even if this be posturing, that it should come days ahead of the upcoming 12th round of corps commander-level talks (likely before mid-August) does not bode well for de-escalation of the prevalent India-China military tensions in eastern Ladakh, which have persisted in the aftermath of the Galwan clashes in June 2020.

Therein lies a taunting message to the West: that these countries failed to live up to New Delhi’s expectations of rallying behind India in the aftermath of Galway. The international community was exposed as being in no position to extend any tangible support to India against China at a critical time. In fact, the US-led West used the India-China stand-off as an issue to advance their own strategic agenda, which included pushing defence deals and flattering India as a Quad groupie to advance their self-serving goals in the ‘Indo-Pacific’.

* The author is Editorial Consultant, WION TV, and a former columnist and Opinion Page Editor of DNA. This article is being republished with the writer’s permission.