An Emerging Threat: Al-Qaeda In The Sinai Peninsula – Analysis

By Robin Simcox

This month’s attacks in Israel were staged from the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. Recent terrorist acts there have led the US to conclude that an al-Qaeda presence has emerged. This will have a significant impact on the entire region, and could further strain relations between Egypt and Israel.

At 12pm on 18 August, twelve militants launched a series of attacks near Eilat, Israel. Automatic weapons, roadside bombs, rocket propelled grenades and suicide belts were used to target passing civilian vehicles, military transport and personnel, killing six civilians and two Israeli soldiers.

The attacks were launched from the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, after the militants tunnelled from Gaza into the Sinai, travelled down the Peninsula and entered Israeli territory. While it is still unclear which group they are aligned to, Israel’s military response has largely been focused on Gaza’s Popular Resistance Committees (PRC) (who praised the attacks but denied involvement).

However, US intelligence officials believe the PRC only scouted locations, and are increasingly focused on the development of terrorist groups loosely aligned to al-Qaeda (AQ) in the region. A new group, al-Qaeda in the Sinai Peninsula (AQSP), has been identified as a potential key participant in the attacks on Israel.

Background: The Sinai Peninsula

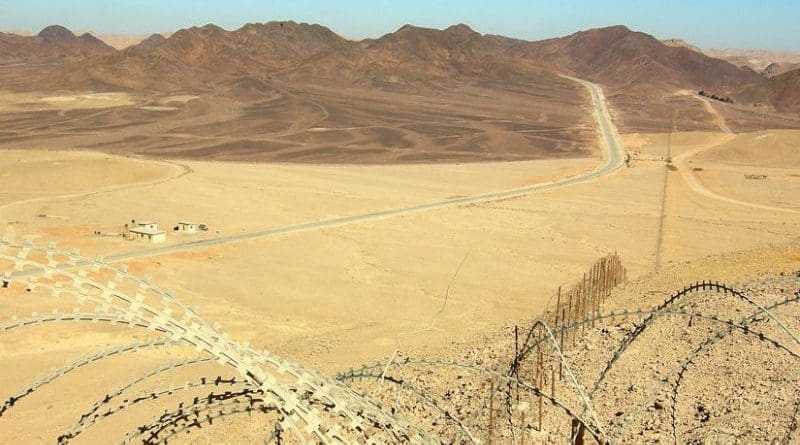

The Sinai Peninsula borders both Israel and Gaza, bridging Africa and Asia. The region was previously under Israeli control following the Six Day War of 1967, but was returned to Egypt as part of the 1978 Camp David accords.

The Sinai is divided into north and south governorates, and comprises four military zones. Zone A (territory to the east of the Suez Canal running north-south) is Egyptian, and possesses a 22,000 man infantry division. Zone B (central Sinai) has four battalions in support of the Egyptian police. Zone C (to the west of the border with Gaza and Israel) is a demilitarised zone under joint control between the Egyptian police and Multinational Force Observers. Zone D (a narrow strip on the east side of the Egypt-Israel border) has four Israeli infantry battalions, including along the Gaza border.

Historically, the Sinai has been beset by tribal disputes. It possesses a large native Bedouin population of approximately 360,000. The Bedouin are a mainly desert based, ethnically Arab group which have long term grievances with the government. The Bedouins have not shared in the economic windfall brought about in the region from tourism and mineral resources, with the tourist industry in the Sinai mainly run by Egyptians from Cairo and other major cities. According to Dr Ely Karmon, a Senior Research Scholar at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism in Herzlyia, the Bedouins have taken to smuggling in response. This has including weapons to Hamas, narcotics, foreign workers and prostitutes, and has especially increased since 2006.

An increasingly lawless region

Since the popular uprisings against Hosni Mubarak began, the Sinai has become an increasingly lawless area. Dr Karmon told HJS that he believes the security situation has ‘collapsed’ and the Sinai is ‘on the way to becoming a failed region’.

The US assessed that 200-300 prisoners were freed from Egyptian jails opened or abandoned in the wake of the uprisings, some of whom subsequently settled in the Sinai, bolstering extremist movements. Joint Palestinian-Egyptian terrorist cells went to the Sinai, seemingly assisted by local Bedouins. Salafist groups have now formed armed committees to settle tribal disputes and police stations have been attacked on multiple occasions. One attack involved militants armed with rocket propelled grenades. Another led to a fire fight in which three civilians died. In response, the Egyptian government – with Israeli consent – deployed military forces into previously demilitarised zones in the Northern governorate.

The situation remains unstable. A Bedouin sheikh told the BBC that the area could be exploited by external actors such as Iran, Hezbollah and AQ. It is possible that such actors (along with Somalia) have now begun to establish training centres and hide weapons caches in the Sinai. Dr Karmon goes as far as to say that the Sinai could become ‘a breeding ground for future al-Qaeda activity’.

The emergence of a new AQ franchise?

Following a recent attack on a police station in the Sinai, a pamphlet and video were produced containing a ‘Statement from Al Qaeda in the Sinai Peninsula.’ The statement called for:

• An Islamic emirate in the Sinai

• The introduction of Sharia law

• The abolition of the Egypt–Israel peace treaty

• Egyptian military intervention on behalf of Hamas in Gaza

• An end to discrimination against the Bedouin population

This mix of jihadist ambitions and Bedouin grievances suggests that either segments of the Bedouin population have either been radicalised by AQ or sympathise with their goals; or, alternatively, AQ activists are deliberately courting the Bedouin, and highlighting issues that concern them for strategic reasons. Either way, following the operation against the police station, a US official commented that there is ‘no longer any doubt that AQ had some kind of potent presence in the peninsula.’ The US believes they have begun to establish basic training facilities and gain strategic control of some towns.

Recently, there have also been bombings on the pipeline that transports gas to Israel, Jordan and Syria. Bruce Riedel, a former CIA officer and current Senior Fellow in foreign policy at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy of the Brookings Institution, told HJS that it was possible that these were the ‘first steps’ of a group (possibly working with Bedouins) aspiring to become part of the AQ franchise and wanting to display their terrorist credentials. This assessment is shared by US officials in relation to the Eilat attacks.

If this is the case, such acts are not going unnoticed. The pipeline bombings were publicly praised by Ayman al-Zawahiri, the new head of AQ, who called for further operations against Israel to take place. (However, there is no consensus that these attacks were linked to AQ. For example, Dr Karmon believes that they were carried out by Palestinians financed by Hizbullah and Iran.)

AQ’s central shura, or committee, has yet to give their formal approval of a franchise operating in the Sinai Peninsula. Yet this does not mean that such a situation could not occur in the coming months. As Riedel explains, negotiations between AQ central and aspirant groups can be protracted as there are certain criteria such aspirant cells must meet. There must be consensus on their enemies; for example, AQ does not want groups focussed solely on local issues at the expense of global goals. More importantly, according to Riedel, they must be operationally capable of violence. He states that there have been many groups in Gaza, for example, that have aspired to be part of the AQ network but have not been approved because they lacked the capacity.

US counterterrorism officials recently briefed the Washington Post that the core AQ leadership was on the verge of collapse. As such, it is possible that AQ may lower the bar in how effective groups have to be in order to get their official branding. Furthermore, their weakness highlights their need to show they are still a relevant organisation. As Riedel asks, ‘what better way is there of doing so than announcing that they have a new franchise, and it is in the heart of the Arab world?’ This being the case, the core leadership may want to officially endorse AQSP sooner rather than later.

What strategic impact could AQ in the Sinai Peninsula have?

The development of an official AQ branch in the Sinai Peninsula threatens the stability of an already chaotic region.

Attacks against Israel and Israeli interests could become commonplace. However, bombing gas pipelines affects not only Israel but also Syria and Jordan, both of whom import gas from Egypt. AQ could also target the Multinational Force Organization present in the Sinai as part of the Camp David accords.

Relations between Egypt and Israel would likely become fractured by AQ militancy in the Sinai. A glimpse of this came in the aftermath of the Eilat attacks. After the terrorists launched their operations, Israeli troops pursued them into the Sinai. One Egyptian officer and two policemen died in the crossfire, as did two Egyptian soldiers in a later incident.

Israel was forced to issue an apology – which may have placated the Egyptian government but has had little effect on the general Egyptian population. Riedel believes popular opinion in Egypt supports renegotiating the current peace treaty with Israel and regards the restrictions placed on their movement in the Sinai as humiliating.

Israel feared such a scenario following Mubarak’s departure. Retention of peace with Egypt is a key goal in Tel Aviv, yet there is uncertainty within the Israeli government over the extent that a post-Mubarak Egypt will be willing to commit to its treaty obligations.

Conclusion

While the situation is bleak in the Sinai, it is not irretrievable. It is too early to describe the Sinai as a failed region in the way parts of Yemen and Somalia are. It will be virtually impossible for AQ to coordinate a takeover in the Sinai. The group does not have the manpower; it has been weakened by bin Laden’s assassination; and they are pinned back in the face of sustained US drone attacks in Pakistan.

There is a risk that the lawless situation could deteriorate further if Israel and Egypt do not work together to prevent it. If AQ was to launch a sustained bombing campaign, it could push Israeli-Egyptian relations to breaking point. Israel would increasingly doubt the willingness of Egypt to restore law and order in Sinai and rein in militant groups, a perception which would only increase were the Muslim Brotherhood to strengthen its presence in the Egyptian Parliament following the upcoming elections.

In order to restore order and achieve their strategic objectives, the three main actors must establish their short and long term goals.

Egypt

A fledgling democratic Egypt cannot allow the Sinai Peninsula to descend into further chaos analogous to Somalia or Yemen. Failure to do so will only allow AQ to embed itself deeper in the region. It should therefore:

• Seek permission from Israel to increase its military presence in particularly lawless areas in the Northern governorate.

• Make steps to resolve the grievances of the Bedouins. The mistrust between the state and the Bedouins cannot be resolved overnight, but the state needs to foster the support of tribal elements in order to isolate terrorist groups.

Israel

Israel’s immediate concern is the threat that an AQ presence on its border poses. It is also reticent about the direction that a post-Mubarak Egypt will take: allowing Egypt to break the terms of the 1979 treaty gives an insight to the strategic importance with which it views the Sinai Peninsula. Israel should therefore:

• Allow Egypt access to the lawless parts of the Sinai which terrorists are seeking refuge in, while seeking assurances concerning their dedication to the Camp of David accords.

• Ensure it hits its target of completing the Israel-Egypt security fence by next year.

US

The US is currently making significant progress against the AQ core in Pakistan. However, it is struggling to contain AQ in Yemen and other affiliates, and does not want a new franchise to develop in the Sinai. To this end, Riedel believes that the CIA has almost certainly already established an intelligence gathering presence in the Sinai. Separately, good Egypt-Israeli relations are a pre-requisite to furthering the Middle East peace process. The US should therefore:

• Encourage Egypt behind the scenes to crack down on terrorist groups in the Sinai.

• Stress to Israel the importance of temporarily accepting an increased Egyptian military presence in the region.

• Lead a concerted international effort to ensure Egypt agrees to respect the Camp of David accords

• The CIA should continue intelligence-gathering on the ground. It needs a flexible approach: as extremist groups grow more entrenched, it will be more dangerous to collect sound data.