Year Ahead: China Mulls More Steps To Spur GDP – Analysis

By RFA

By Michael Lelyveld

As China faces another year of slower economic growth, the government is preparing “contingency plans” that could have a significant impact on energy use and the environment.

On Dec. 12 at the close of its annual central economic work conference, the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the government issued a statement calling for unspecified measures to prevent a further fall in growth rates in the coming year.

“The global economy continues to slow down, the world is still undergoing in-depth adjustments due to the global financial crisis, profound changes are accelerating, and sources of turbulence have substantially increased,” said the statement cited by the official Xinhua news agency.

“We need to be well prepared with contingency plans,” it said.

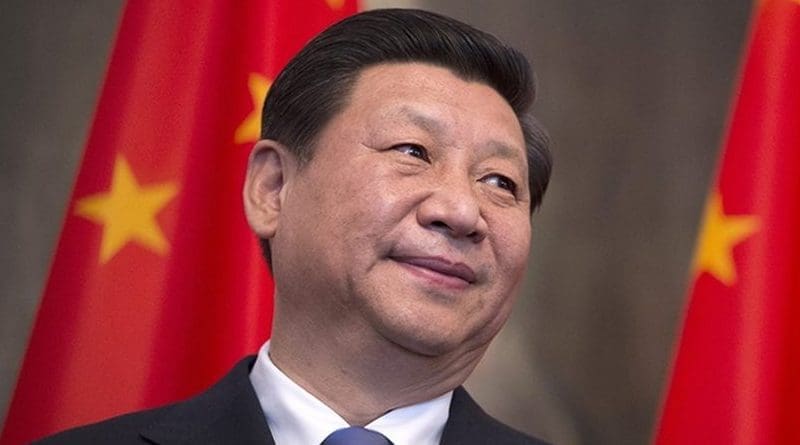

The key two-day meeting addressed by President Xi Jinping heaped praise on the party leadership for progress in fighting Xi’s “three tough battles” against financial risks, poverty and pollution in the past year.

But the tone of the conference appeared less confident than previous meetings during Xi’s tenure.

“While fully acknowledging our achievements, we must see that China is at a pivotal stage of transforming its growth model,” the statement said, adding warnings against “downward economic pressure” and “intertwined structural, institutional and cyclical problems.”

The statement came just a day before the announcement of a “Phase One” agreement with the United States to avert a new wave of tariffs, but there were no signs that the development would change the tenor of the planners’ outlook for the year.

China’s GDP growth rates have declined more or less steadily since 2010, long before the start of the trade war in 2018.

The conference has traditionally agreed on economic growth targets for the coming year without revealing them, leaving the official pronouncement to Premier Li Keqiang when he presents the government’s work report at the annual legislative sessions in March.

But there seems to be little suspense this time about what the 2020 target for gross domestic product will be, particularly after third-quarter growth fell to 6 percent, its slowest pace since at least 1992.

The government is likely to hold the target line at “around 6 percent,” stepping down only slightly from the 6.0-6.5 percent range of goals for 2019, the South China Morning Post said.

In the days before the conference, the Chinese Academy for Social Sciences (CASS) paved the way for the prediction with a forecast that GDP growth would maintain the level of “about 6 percent.” CASS expects a 6.1-percent rate in 2019.

Political test for CPC

But behind the quibbling about one-tenth of 1 percent of growth lies a major political test for Xi and the CPC.

The 2020 target will weigh heavily on China’s leaders throughout the year because of the pledge made by former President Hu Jintao that China’s GDP in 2010 would double in a decade.

The target is generally thought to require growth of 6.1-6.2 percent, but at 6 percent, the call will be close.

In October, the International Monetary Fund lowered its China forecast for 2020 from 6 percent to 5.8 percent, probably putting the decade-of-doubling out of reach, although the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) could still save the day with revised rates for past years.

On Friday, the NBS said it will release revised figures for 2018 along with GDP results for 2019 as part of a long- planned reform to make regional accounting consistent with national estimates.

The numbers game may mean little outside China. Even within the country, it is unlikely to have much relevance for the changes and challenges that the economy will face in the coming year.

But the government’s warning about the pressing need for contingency plans suggests a high-stakes struggle to save the GDP numbers, supporting the government’s claim that China has shifted to a growth model based on consumption, services, higher-quality production and technology from old-style industrial output and exports.

Last January, Li began the year by promising that the government would not resort to the economic stimulus policies of the past, a reference to the 4-trillion yuan (U.S. $571-billion) package of infrastructure projects in 2008-2009 that spurred GDP but left China mired in pollution and debt.

“The government will strive to innovate and improve its macroeconomic regulation but not resort to massive economic stimulus,” Xinhua quoted Li as saying.

But after quarterly growth rates slowed steadily through the past year, a big shot of fiscal stimulus seems to be exactly what the government is considering in its contingency plans, said Gary Hufbauer, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“My guess is a big fiscal stimulus plan — lots of spending on infrastructure and environment. Say, 1.5 percent of GDP,” Hufbauer said by email.

“Maybe, as well, some relaxation of bank credit, but the authorities are wary of low-grade debt expansion,” Hufbauer said.

The double-decade line

A stimulus of that size might be about half as big as the 2008-2009 package in current dollar terms, but it could be enough to push GDP over the double-decade line.

Last week, Minister of Transport Li Xiaopeng outlined bigger spending plans totaling nearly 2.7 trillion yuan (U.S. $386 billion) for transportation alone, including projects for railways, roads and civil aviation facilities.

On Dec. 19, a report by the official English-language China Daily cited experts as supporting the stimulus plans.

“Fiscal deficit is expected to expand next year as strong support from the local government special bonds will help stabilize infrastructure investment,” it said.

Over the past year, the central government’s green light for local bond issuance has made the real pace of stimulus spending harder to track.

In the first 11 months, local governments issued bonds valued at 4.32 trillion yuan (U.S. $618 billion), including 2.55 trillion yuan (U.S. $364.8 billion) of special-purpose bonds to fund “public interest projects,” the Ministry of Finance said.

Strengthening the case for more stimulus, China’s regulators have tried almost everything else.

Among the moves, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in September cut the reserve requirement ratio (RRR), governing the amount of cash that banks keep on hand, for the third time last year, after five cuts in 2018.

On Dec. 23, Premier Li said the government is considering more RRR cuts, according to another China Daily report.

In November, the central bank sought to ease liquidity further with an overhaul of interest rates, introducing a one-year loan prime rate “to better indicate the real lending cost to companies.”

The PBOC has been trying to deliver on the government’s pledge to make more loans available to private and small businesses in an attempt to overcome the bias in favor of less productive state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

New bank loans in November rose 11 percent from a year earlier to 1.39 trillion yuan (U.S. $198.6 billion) after an October lull.

But worries over debt and financial risks have reined in more drastic moves, at least until now.

China’s outstanding bank loans now exceed U.S. $17 trillion (118.8 trillion yuan), The Wall Street Journal reported, citing financial data provider Wind.

Unusual growth measures

The government has also tried to revive the economy with major fiscal steps in the past year, including a projected 2.3 trillion (U.S. $328 billion) in tax and fee cuts, easing business burdens by slashing social security contributions.

In other moves, the government has resorted to some unusual non-financial growth measures that may suggest desperation, such as promoting tourism and nighttime activities.

Despite the implications for energy use and the environment, the government has cut electricity rates for industrial and commercial users for the second year in a row, burying the costs in various segments of the power sector.

Another cut is in the works for the coming year.

The country’s latest official economic readings have been largely flat, providing little basis for a return to higher GDP growth.

Industrial production rose 6.2 percent from a year earlier while 11-month output edged up 5.6 percent, the NBS said.

Retail sales increased 8 percent in both the November and 11-month periods as auto sales continued to drag for the 17th consecutive month, according to Reuters.

Fixed-asset investment, reflecting spending on infrastructure and other capital items, rose 5.2 percent through November, while private sector investment advanced 4.5 percent.

Power generation, a surrogate indicator of economic activity, gained 4 percent from a year earlier in November and only 3.4 percent in the first 11 months, the NBS said.

Monthly production of infrastructure-related commodities like steel and cement has been mixed.

Crude steel output was up 4 percent from a year before in November after double-digit growth rates earlier in the year.

But cement production climbed 8.3 percent in November, boosting 11-month output to a 6.1-percent gain.