Who Discovered America?

By VOA

By Kevin Enochs

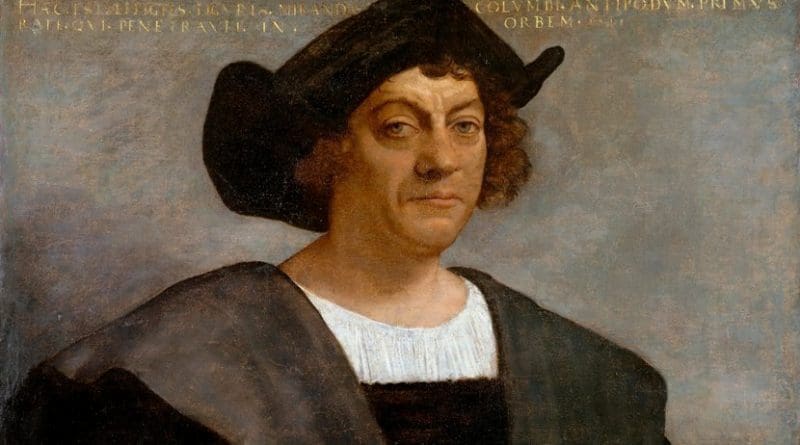

Americans get a day off work on October 12 to celebrate Columbus Day. It’s an annual holiday that commemorates the day on October 12, 1492, when the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus officially set foot in the Americas, and claimed the land for Spain. It has been a national holiday in the United States since 1937.

It is commonly said that “Columbus discovered America.” It would be more accurate, perhaps, to say that he introduced the Americas to Western Europe during his four voyages to the region between 1492 and 1502. It’s also safe to say that he paved the way for the massive influx of western Europeans that would ultimately form several new nations including the United States, Canada and Mexico.

But to say he “discovered” America is a bit of a misnomer because there were plenty of people already here when he arrived.

And before Columbus?

So who were the people who really deserve to be called the first Americans? VOA asked Michael Bawaya, the editor of the magazine American Archaeology. He told VOA that they came here from Asia probably “no later than about 15,000 years ago.”

They walked across the Bering land bridge that back in the day connected what is now the U.S. state of Alaska and Siberia. Fifteen-thousand years ago, ocean levels were much lower and the land between the continents was hundreds of kilometers wide.

Beringia land bridge

The area would have looked much like the land on Alaska’s Seward Peninsula does today: treeless, arid tundra. But despite its relative inhospitality, life abounded there.

According to the U.S. National Park Service, “the land bridge played a vital role in the spread of plant and animal life between the continents. Many species of animals – the woolly mammoth, mastodon, scimitar cat, Arctic camel, brown bear, moose, muskox, and horse — to name a few — moved from one continent to the other across the Bering land bridge. Birds, fish, and marine mammals established migration patterns that continue to this day.”

And archaeologists say that humans followed, in a never-ending hunt for food, water and shelter. Once here, humans dispersed all across North and eventually Central and South America.

Up until the 1970s, these first Americans had a name: the Clovis peoples. They get their name from an ancient settlement discovered near Clovis, New Mexico, dated to over 11,000 years ago. And DNA suggests they are the direct ancestors of nearly 80 percent of all indigenous people in the Americas.

But there’s more. Today, it’s widely believed that before the Clovis people, there were others, and as Bawaya says, “they haven’t really been identified.” But there are remants of them in places as far-flung as the U.S. states of Texas and Virginia, and as far south as Peru and Chile. We call them, for lack of a better name, the Pre-Clovis people.

And to make things more complicated, recent discoveries are threatening to push back the arrival of humans in North America even further back in time. Perhaps as far back as 20,000 years or more. But the science on this is far from settled.

Back to the Europeans

So for now, the Clovis and the Pre-Clovis peoples, long disappeared but still existent in the genetic code of nearly all native Americans, deserve the credit for discovering America.

But those people arrived on the western coast. What about arrivals from the east? Was Columbus the first European to glimpse the untamed, verdant paradise that America must have been centuries ago?

Not even close.

There is proof that Europeans visited what is now Canada about 500 years before Columbus set sail. They were Vikings, and evidence of their presence can be found on the Canadian island of Newfoundland at a place called l’Anse Aux Meadows. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage site and consists of the remains of eight buildings that were likely wooden structures covered with grass and soil.

Today the area is barren, but a thousand years ago there were trees everywhere and the area likely was used as winter stopover point, where Vikings repaired their boats and sat out bad weather. It’s not quite clear if the area was a permanent settlement, but it is clear that the expansion-minded Norsemen were here long before Columbus.

One final mystery

And to add one fascinating wrinkle to the story of America’s discover, consider the Sweet Potato.

Yes, that’s right the sweet potato. This humble pinkish-red tuber is native to South America. And yet, there have been sweet potatoes on the menu in Polynesia as far back as 1,000 years ago. So how did it get there?

By comparing the DNA of Polynesian and South American sweet potatoes, scientists think it’s clear that someone either brought them back to Polynesia after visiting South America, or islanders brought them from South America when they were exploring the Pacific Ocean. Either way, it suggests that about the same time Nordic sailors were cutting trees in Canada, someone in Polynesia was trying sweet potatoes from South America for the first time.

Speaking of genetics, a 2014 study of the DNA of natives on the Polynesian island of Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, found a fair amount of Native American genes in the mix. The entry of American DNA into the genetics of the Rapa Nui natives suggests that the two peoples were living together around 1280 AD.

There are other theories out there. A retired British Naval officer named Gavin Menzies has been pushing the idea that the Chinese colonized South America in 1421.

Another theory from a retired chemist named John Ruskamp suggests that pictographs discovered in Arizona are nearly identical to Chinese characters. He puts the Chinese in the U.S. state of Arizona sometime around 1300 BC.

We mention these two only because we have seen them pop up in newspaper articles recently. They’re thoroughly discredited, so we’ll leave it at that.

A melting pot indeed

So what to make of all this?

Well, here at VOA, we are trying to tell the story of America. And what is clear is that America was a melting pot hundreds of years before the Statue of Liberty began urging the world, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

In fact, the entirety of North and South America are a polyglot of cultures stretching back before recorded history. And people have been coming here ever since, chasing a better life, abundant food, water and opportunity.

Today, maybe not that much has changed.