Tides Of Change In Iran And US: Implications For Philippines – Analysis

By FSI

By Andrea Kristine G. Molina*

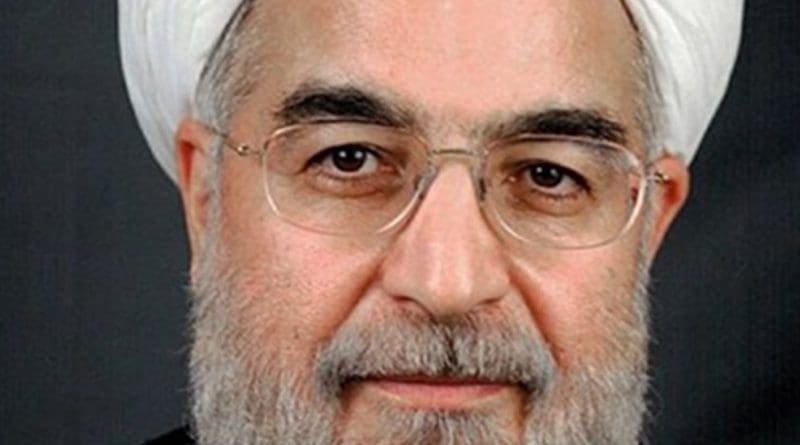

Since the change of administration in the United States, there has been declining enthusiasm to move forward the Joint Cooperation Plan of Action (JCPOA) or the Iran nuclear deal. US President Donald Trump’s vocal, antagonistic stance on Iran sparked an exchange of rhetoric and provocative actions and reactions between the US and Iran, with Trump going as far as calling the agreement “the worst deal ever negotiated”; thus, quickly overturning the conciliatory political climate cultivated during the administrations of former US president Barack Obama and the moderate and pragmatic Iranian president Hassan Rouhani. Trump’s election is one thing; the upcoming presidential election in Iran on May 19 is another. Given the domestic developments in Iran, it is clear that the outcome of the elections will be crucial to the fate of the nuclear deal and Iran’s current global and regional position.

Boon and bane for Rouhani

The nuclear deal has undeniably catapulted Iran’s regional and global standing. By forging a deal, the major powers essentially acknowledged that Iran is a state that the world cannot afford to ignore. Rouhani’s openness to restore engagement with the West also earned the world’s trust on Iran’s sincerity in ensuring the peaceful nature of its nuclear program. The lifting of economic sanctions in January 2016 and the partial liberalization of the economy spurred excitement among foreign businesses keen on tapping the 80 million-strong market and raised expectations among ordinary Iranians feeling the brunt of the sanctions.

Since 2016, the United Kingdom restored its diplomatic relations with Iran while other European countries successfully sealed massive investment deals on infrastructure and offshore gas field development. Iran is also slowly regaining market share in Europe and Asia, which it lost due to economic sanctions. Amid the oil glut, the country capitalized on the OPEC output cut deal from which it is exempted and stepped up its efforts to expand its market, albeit with caution over the residual risks of US sanctions. Major Asian buyers increased their imports by 60 percent since the sanctions were lifted. In December 2016 alone, a Reuters report stated that China, India, Japan, and South Korea doubled their imports at 1.89 million barrels per day (bpd). The Philippines, which has ceased oil imports from Iran since 2012 following the imposition of sanctions, is now planning to resume oil imports from Iran. Pergas Consortium, a group composed of European and Asian oil companies, which includes the Philippine National Oil Company, is also reportedly planning to build a liquefied natural gas plant in Iran to help Iran’s oil and gas industry to recover.

Moreover, Iran’s tourism sector post-JCPOA experienced significant growth, benefiting from the improvement of Iran’s international image and positive atmosphere brought by the nuclear deal. This brought in billions of dollars in revenue over the years and generated badly needed jobs to an economy largely affected by the economic sanctions and the oil glut. The Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts, and Tourism Organization (ICHTO) noted that 5.2 million tourists arrived in 2015 and increased by 18.3 percent in 2016, according to Forward Keys. Officials envision 20 million arrivals by 2025 under their 2025 Tourism Vision Plan and hope to reduce their reliance on oil for national revenues. Iran has been busy investing in tourism infrastructure development and attracting foreign investors to accommodate the expected surge of tourists.

Since Rouhani took office, Iran has also strengthened its partnerships with Asian countries. It has been improving its connectivity with the Caucasus, Central Asia, India, and China through cross-border transport infrastructure development such as the Iran-Turkmenistan-Kazakhstan railway, North-South Transport Corridor, and Yiwu (China)-Tehran railway. China, Iran’s biggest trading partner, stands to benefit from these developments and sees Iran as a crucial part of its “Belt and Road Initiative.” Furthermore, Iran is keen on strengthening agricultural, banking, and energy cooperation with Southeast Asia through both bilateral and multilateral platforms. It has expressed interest in importing more bananas from the Philippines, as well as investing in power transmission and water purification projects. In 2016, Rouhani made a three-country tour in Southeast Asia and attended the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) in Bangkok to stimulate trade and investment.

Rouhani’s chances for reelection, however, are challenged by a myriad of domestic and global issues. On the domestic front, the nuclear deal struggles to meet the high expectations of its promised economic benefits. Political opponents claim that the nuclear deal has not really improved the lives of ordinary Iranians. Iran still struggles to address its crippling unemployment, further worsened by issues of corruption, government mismanagement, and complex bureaucratic hurdles. These issues took their toll in the city of Ahvaz in the oil-rich Khuzestan province where unemployment and environmental crisis sparked political unrest.

The powerful conservative political elites often take advantage of such discontentment and a perceived lack of economic progress to gain a political edge over the moderates. Iran’s heavily factionalized political system pit the moderates, reformists, and conservatives against one another. Despite the moderates winning more seats in the parliament in the 2016 elections, the conservatives, consistently favored by the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, have control over Iran’s powerful institutions, including the Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The IRGC, which Trump considers designating as a terrorist organization, runs Iran’s policy elsewhere in the region, particularly in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, and Afghanistan; thus essentially undermining Rouhani’s foreign policy agency.

Without the political support of the late influential leader Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and of disillusioned Iranian minorities and reformists, Rouhani is facing tougher competition against the conservatives who are aggressively campaigning against him and are vocal in their opposition to the JCPOA. Neither does it help that Ayatollah Khamenei has recently rebuked Rouhani’s economic policies and has called for “resistance economy” or economic self-sufficiency, even as Rouhani claims “unprecedented economic growth” in his Nowruz address. Indeed, Rouhani is faced with the difficulty of selling the JCPOA domestically and convincing ordinary Iranians of its eventual economic benefits.

Post-election outlook and opportunity for the Philippines

For now, Rouhani remains in a strong position as reformists seeking greater political and social freedoms have no other better choice but Rouhani. However, continued political polarization and Trump’s more aggressive, hardline policy puts Iran in an uncertain future. The nuclear deal, in particular, remains vulnerable and there is a possibility that the US will unilaterally impose further sanctions and refuse to lift the remaining restrictions on the banking sector. Also, Iran’s conservatives are strongly opposed to the nuclear deal and might fully abandon it once they reclaim the presidential seat. Regardless, these global and domestic developments could push Iran to fully disengage from the global economy and focus instead on self-sufficiency.

These challenges should not hinder neutral countries from sustaining engagement with Iran. The Philippines, one of Iran’s oldest partners in Asia, should uphold a policy of neutrality in the US-Iran row, so long as it does not affect regional stability and jeopardize Philippine interests. Iran’s recent economic and political overtures in the East signals Iran’s growing interest in expanding relations with the region amid the slow and fragile rapprochement with the West. For now, the Philippines could take advantage of Iran’s engagement with Asia by penetrating the Iranian market, tapping the oil and gas industry, and boosting people-to-people relations through education, sports, and tourism. It is also in the Philippines’ best interest to support the successful implementation of the JCPOA on both bilateral and multilateral levels not only to ensure the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear program but also to improve cooperation on issues of mutual interest.

While Iran’s elections may not significantly affect Philippines-Iran relations, the elections in May will be pivotal to Iran’s direction and its position on the global stage. To some degree, the world has a stake in the results of the elections as it did when Rouhani was first elected.

About the author:

*Andrea Kristine G. Molina is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. Ms. Molina can be reached at [email protected]

Source:

This article was published by FSI. CIRSS Commentaries is a regular short publication of the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (CIRSS) of the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) focusing on the latest regional and global developments and issues.

The views expressed in this publication are of the authors alone and do not reflect the official position of the Foreign Service Institute, the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Government of the Philippines.