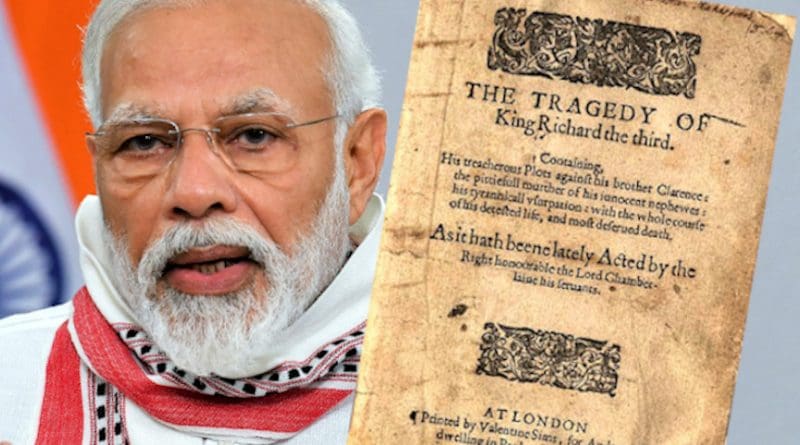

What India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi And Members Of Opposition Should Read – OpEd

By Prakash Kona

If I could get hold of a Gujarati translation of Shakespeare’s King Richard the Third I would be glad to give a copy of it to Prime Minister Narendra Modi so that he can use it as bed-time reading and reflect on certain aspects related to his own self and his position as the man at the helm of a giant ship called Indian polity which is not too far from colliding with an iceberg.

King Richard the Third is a lab manual in performance and acting. It is a meta-text and meta-theatre because it tells you how to act and what is the theoretical basis of drama. Every person who ever dreamt of becoming an actor should go through this play to acquire clarity on what it means to be one. Actors are both born and made; but there is a kind of actor who intends to defeat fate itself through his astonishing powers to manipulate reality owing to his masterly performative skills. At any point in the play Richard III is part of a performance that he is directing within his mind even while he is playing the role that he has invented for himself. As a performer he intends to gain complete control over reality through the genius of acting. Unlike normal mortals who are subject to fate, Richard III believes that he must play the role of fate itself and control the lives of people. Thus he dedicates his life to perfecting the one thing he knows how to do best: which is to act.

The aesthetic value of Richard’s performance comes from his ability to eliminate any sort of feeling and morality from acting. To Richard, acting must have nothing to with morality or empathy. There is a strange amoral quality to performance and all great actors acquire their powers through their capacity to prevent feelings from entering a role. On one side, the method actor identifies himself with the character. On the other side, the alienated performer in Brecht’s plays reminds the audience that he or she is an actor lest the onlooker gets caught up with the illusion of performance. In films, Italian neo-realist cinema created the non-acting actor out of the materials of life itself.

Like all true actors, Richard changes depending on the situation: from a method actor he becomes an alienated performer and from the latter he moves into a neo-realist non-acting actor.

My favorite part in the play is when Richard as Duke of Gloucester, in one of those seemingly innocuous conversations that happen in serious moments of a drama, asks Buckingham about the latter’s acting prowess:

Come, cousin, canst thou quake, and change thy colour,

Murder thy breath in the middle of a word,

And then begin again, and stop again,

As if thou wert distraught and mad with terror?

The Duke of Buckingham proudly responds to Richard, not knowing that he is talking to the epitome of all great acting itself:

Tut, I can counterfeit the deep tragedian;

Speak and look back, and pry on every side,

Tremble and start at wagging of a straw,

Intending deep suspicion: ghastly looks

Are at my service, like enforced smiles;

And both are ready in their offices,

At any time, to grace my stratagems.

This is a darkly funny moment in the play because as audience we know that Buckingham’s days are numbered and he is one of those many people who are going to be destroyed by Richard without any compunction. Yet, it is amusing when you see that Buckingham’s acting skills, that he is so proud of, are nowhere remotely close to those of Richard III. Buckingham can “counterfeit the deep tragedian” by becoming the role, thereby allowing the audience to judge him; with Richard III, he is his own judge and the audience are a part of the tragedy.

Yet, there is one thing that Richard forgets in his obsession to be a versatile performer. An accomplished actor need not feel with his role or with the lives of those around him. But, what an actor cannot afford to do is believe in his own skills to such an extent that he cultivates a narcissistic admiration of his own greatness and in the process begin to slowly turn delusional.

That is sadly what is happening to Prime Minister Narendra Modi over a period of time; he is beginning to see himself not as a Prime Minister through popular representation but as a king divinely ordained to rule this country. In the last years of her life, the late Prime Minister Indira Gandhi too suffered from a similar self-infatuation bordering megalomania.

Richard III is not a tragedy for the lives destroyed by the king. It is a tragedy of how power destroys a person who is caught up with it. Hence, the title in the First Quarto was given as: The Tragedy of King Richard III. Shakespeare rightly understood that the tragedy is not so much for the victims of Richard’s cruelty and malice as much as it is for the king himself who allows power to destroy him from within leaving a vacuum where there ought to have been a human person. A victim is by definition innocent and innocence will save a person morally and spiritually. A victimizer is not innocent and has to pay for the wrongs he does to others. Being a victimizer makes Richard III’s life nothing but a tragedy.

Acting is a skill; you cannot turn a skill into a source of power for you to destroy the lives of people without any guilt. Power is a notion and an idea. At the end of the play, at that very point when his defeat seems imminent in the hands of Richmond (the future Henry VII), Richard cannot understand what went wrong and why; in one of the profound soliloquies in all of the history plays, Richard, haunted by the ghosts of his victims wakes up and exclaims:

O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me!

The lights burn blue. It is now dead midnight.

Cold fearful drops stand on my trembling flesh.

What do I fear? myself? there’s none else by:

Richard loves Richard; that is, I am I.

Is there a murderer here? No. Yes, I am:

Then fly. What, from myself? Great reason why:

Lest I revenge. What, myself upon myself?

Alack. I love myself. Wherefore? for any good

That I myself have done unto myself?

O, no! alas, I rather hate myself

For hateful deeds committed by myself!

I am a villain: yet I lie. I am not.

Fool, of thyself speak well: fool, do not flatter.

My conscience hath a thousand several tongues,

And every tongue brings in a several tale,

And every tale condemns me for a villain.

Perjury, perjury, in the high’st degree

Murder, stem murder, in the direst degree;

All several sins, all used in each degree,

Throng to the bar, crying all, Guilty! guilty!

I shall despair. There is no creature loves me;

And if I die, no soul shall pity me:

Nay, wherefore should they, since that I myself

Find in myself no pity to myself?

Methought the souls of all that I had murder’d

Came to my tent; and every one did threat

To-morrow’s vengeance on the head of Richard.

This is the part of the play that I think Mr. Modi should ask his secretary to take a printout and give it to him so that he pastes it on the wall of his office and reads it at least once every day. The ghosts of the victims of a communally divided India, those who died or are deprived of their life’s meager savings because of demonetization, countless youth without jobs or a future thanks to the economic policies of the government that has put corporate interest before every other, victims of brutal repression, riots and lynch mobs, poor migrant labor trudging along the roads in the mid-day heat towards an unknown destination called home with their families and their non-existent futures – all of this is bound to come back and ask questions of the man who had the opportunity to do things differently but was so caught up with his own image of himself that he became oblivious to human dignity.

A man may have power over others. Yet, he is still a puppet in the hands of an abstraction called power. He is dancing to a tune over which he has no control. At the end of Shakespeare’s play the ghosts are united against Richard III despite all their differences in life because the dead are not affected by the preoccupations of the living. Richmond is the embodiment of the will of others, which includes the countless dead, who will assist him in destroying Richard III thereby putting an end to the vicious cycle of violence that resulted from the civil unrest caused by the Wars of the Roses.

It is imperative for Mr. Modi to remember that there are limits to performance, any performance, however brilliant it might be. It is easy to become delusional and imagine that power is emanating out of some intrinsic qualities that you possess as a person. Nothing is further from the truth. Power is a notional thing; you cannot for a moment be seduced by the thought that you embody that notion in an esoteric way that goes beyond explanation. In fact most powerful men who thought that they were invincible actually succumbed at the point that delusion got the better of reality.

While Modi ought to know that his illusions of grandeur are delusions of a man plunging headlong into disaster, I intend to give a copy of Machiavelli’s The Prince to the clueless, pathetic, insincere, corrupt and divided members of India’s opposition parties. Modi might have the cunning and the deviousness of a man destructively obsessed with power. But, he is as vulnerable as any ordinary person for no other reason except that he is an ordinary person in power; the aura of authority emanating from his presence is only an image and a persona created by the instruments of power mainly the media and culture industry.

As Chaplin points out in The Great Dictator there is nothing fundamentally significant that separates the Jewish barber from Adolf Hitler just as there is no difference between a man who sells tea and the head of a country. We just have to see people for what they are: perfectly ordinary. Being in a position of authority doesn’t make them any less ordinary. In a memorable scene from the movie Enter the Dragon (1973) when fighting the evil Han in a hall of mirrors, Lee remembers the Shaolin Abbot’s words: “The enemy has only images and illusions behind which he hides his true motives. Destroy the image and you will break the enemy.”

That’s what Machiavelli’s understanding of politics is about: you have to break your enemy by destroying the image he has of himself. The opposition has to work in unity to destroy Modi’s image of himself behind which he hides his true motives. As Gramsci observes in his essay, “The Modern Prince,” Machiavelli’s style is that “of a man of action, of a man urging action, the style of a party manifesto.” Insisting that one must recognize the “essentially revolutionary character” of Machiavellianism, Gramsci says that Machiavelli’s ““ferocity” is turned against the residues of the feudal world, not against the progressive classes. The Prince is to put an end to feudal anarchy.” The modern Prince for Gramsci is not someone like Richmond in Shakespeare’s play, a real, concrete person, but a “political party – the first cell in which there come together germs of a collective will tending to become universal and total.”

The whole point of being a political party in the opposition is that you don’t do what the party in power is doing. You have to provide an alternative that is not only a real alternative but also looks like one. As of now, the party in power has managed to successfully portray the principal opposition party and its allies as not only ineffectual and incompetent but also as anti-national and anti-majority. More than the nobility, the Prince according to Machiavelli, must invest on common people since their expectations are much more modest and often they are happy enough and thankful if they are not oppressed. Machiavelli adds:

“When the prince who builds his foundations on the people is a man able to command and of spirit, is not bewildered by adversities, does not fail to make other preparations, and is a leader who keeps up the spirits of the populace through his courage and his institutions, he will never find himself deceived by the common people, and he will discover that he has laid his foundations well.”

This is what the opposition parties ought to do with a single-minded dedication: befriend the common people, not on Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp or any of the social networking sites but through conventional gatherings that used to be popular in the past. Common people like to speak and listen to their leaders in person. Even if that is not always possible sometimes a glimpse of one’s leaders is enough to produce positive results. Through making themselves accessible at the grassroots, and giving the poor an opportunity to articulate their needs, I don’t think defeating a political party that so far has been thriving merely on an image and not on reality is such a big task. Contrarily, good fortune, a change of mind in the masses or an unexpected natural intervention – for the opposition to hope that any one or all of these things will turn the winds in their favor on the day of the election is nothing but sheer stupidity and abject surrender.

*Prakash Kona is a writer, teacher and researcher who lives in Hyderabad, India. He is Professor at the Department of English Literature, The English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU), Hyderabad.