China’s New Global Role: President Xi In Washington And UN – OpEd

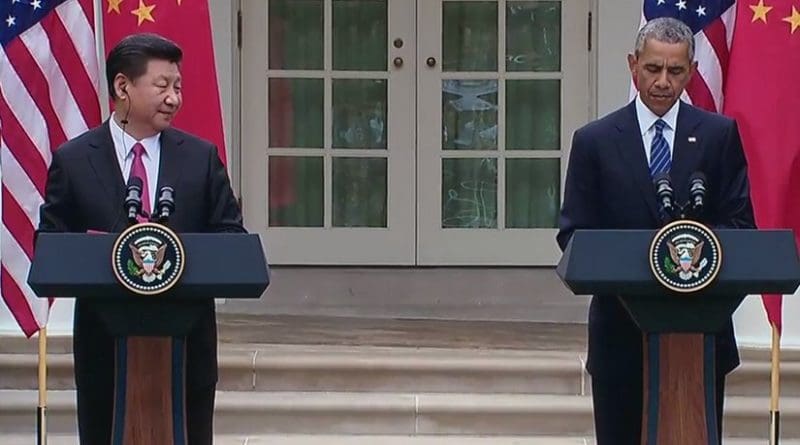

The recent Washington summit took the US-China bilateral relations onto a new level, while President Xi’s UN visit gave a glimpse of China’s new global role.

Currently the U.S.-China bilateral relations are characterized by very different trajectories of power. As President Barack Obama is on his way out, President Xi Jinping is just getting started. In turn, the U.S. presidential election cycle, particularly its aggressive rhetoric, may cast shadows over bilateral progress.

Before the summit, there was much speculation in the United States about China’s ability and willingness to execute reforms amid challenges in the mainland and a volatile international environment. At the eve of his first state U.S. visit, President Xi addressed these concerns in a Wall Street Journal interview. “Like an arrow shot that cannot be brought back,” he said, “we will forge ahead against all odds to meet our goals of reform.”

Xi’s aim was to deter any concern that China is faltering in its transition toward more sustainable growth. That interview differed from those of an elder generation of Chinese leaders. It was plain-speaking, diplomatic but clear, and confident. And it precipitated the successes of the summit.

Significant economic progress

As President Xi concluded his state visit, the summit had resulted in almost 50 tangible outcomes that reflect significant progress and possibly substantial breakthroughs.

Trade, investment and tourism. Last year, U.S.-China trade amounted to $592 billion. China is America’s second-largest trading partner, third-largest export market, and biggest source of imports. Despite periodic friction, these ties are expanding. Even as U.S. presidential campaigns continue to blame China for “taking our jobs,” Beijing and Washington are completing the highly-anticipated U.S.-China bilateral investment treaty (BIT). A similar momentum prevails in people-to-people exchanges as the two nations made 2016 the U.S.-China tourism year.

Internationalization of the Renminbi. Intriguingly, although Washington has stayed out from the new China-proposed development banks (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, BRICS New Development Bank), the two may have agreed to facilitate Renminbi trading and clearing in the United States. Wall Street cannot be a bystander as London is busy building a Shanghai-London Stock Connect, reminiscent of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Connect.

Climate change. Last fall, the United States unveiled its target to cut greenhouse gas emissions 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, while China disclosed its target to peak emissions around 2030 and increase the non-fossil fuel share of energy to about 20 percent by 2030. However, last week, cooperation moved to a new plane as China announced the 2017 launch of a nationwide carbon-emissions trading system that will cover heavy pollution sectors, such as iron, steel, power generation, paper, aluminum and chemicals, which account for three-quarters of China’s energy-related carbon emissions. Through the China South-South Climate Cooperation Fund, Beijing also pledged $3.1 billion to help countries address climate change.

In the process, China expanded the pool of major donors beyond just industrialized countries. The bilateral joint statement signals that both nations are now fully committed to a successful global agreement in Paris.

Vital strategic gains

The most impressive steps were taken in cyber security; a highly contested and secretive part of the bilateral agenda.

Cybersecurity. After Edward Snowden’s dramatic disclosures about massive worldwide cyber hacking by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and U.S. allegations about hacking by Chinese military, bilateral cyber security talks were suspended a year ago. Now both nations pledged to refrain from state-sponsored cyber theft of intellectual property, while announcing they would launch a bi-annual high-level dialogue mechanism on fighting cyber theft by the end of the ongoing year.

Military. In military relations, Washington and Beijing expanded their cooperation on confidence building measures to include air-to-air safety and crisis communications. The latter is particularly critical as both sides remain concerned about accidental crisis events that could unleash unnecessary hostilities without appropriate communications safeguards.

Anti-corruption cooperation. In the anti-graft activities, the two nations pledged to enhance cooperation on criminal investigations, repatriation of fugitives and asset recovery issues. This is vital for the Chinese anti-corruption struggle; a core part of President Xi’s domestic agenda led by Wang Qishan. But the pledge is also important in the United States to send a signal that America is not a harbor for corrupt foreign political leaders.

However, the gains of the Washington summit went beyond the core bilateral economic and strategic agenda.

Regional and global cooperation

By conservative estimates, the U.S. military occupies almost 700 “base sites” outside America, while an increasing share of its military capacity is shifting to Asia Pacific. In a recent interview, Xi said pointedly that “China has no military base in Asia and stations no troops outside its borders… The Asia-Pacific should be a cooperative ground for enhanced China-U.S. coordination and collaboration rather than their Coliseum for supremacy.”

Possible rapprochement in South China Sea disputes. In Washington, the White House presented its traditional concerns about the regional disputes, while Xi reiterated China had the right to uphold its territorial sovereignty, but also said it did “not intend to pursue militarization” of the artificial islands built in the region. In the summit, there may have been progress in the South China Sea issue. The two nations may share a tacit understanding on what is acceptable and what is not in the South China Sea.

Regional free trade. In Asia Pacific, the White House has lobbied to undermine China’s free-trade plans, while seeking to complete its controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement. Yet, the TPP leaves out China, India, and Indonesia; Asia’s three largest economies. In the short-term, Washington seeks to complete the TPP; in the medium-term, the White House knows only too well that any major Asia-Pacific free trade deal must make room for both the U.S. and China.

In the White House, President Xi highlighted the potential of the U.S.-Chinese bilateral relations. In the United Nations, he shifted the spotlight on China’s bilateral cooperation with the U.N.

Permanent peacekeeping. In his first address to the U.N., President Xi said that China would set up a permanent peacekeeping force of 8,000 troops and contribute another $100 million in military assistance to the African Union for peacekeeping missions in the next half a decade.

Development investments. China will set up a “China-U.N. peace and development fund with an initial pledge of $1 billion to support developing countries to realize a broad “post-2015″ global sustainable development agenda.” Moreover, Beijing will continue to increase investment in the least-developed countries (LDCs), aiming at a total of $12 billion by 2030. Finally, China shall forgive some debts owed by the LDCs this year while launching some 600 projects to cut poverty and boost development overseas in the next five years.

China’s new global role

For a decade, China has been accused in the West for not being a “responsible stakeholder” internationally. In reality, Beijing has been reluctant to embrace institutions whose structures, leaders and policies were dictated by advanced economies in the postwar era.

As President Xi’s visit to Washington and the UN suggests, Beijing has begun to influence those structures, their leaders and policies in a way that respects the past role of the advanced economies, but will make room for the increasing economic and strategic role for emerging, developing and least-developed countries.

“China will never seek hegemony, expansionism or a sphere of influence,” Xi said in the U.N., adding that militarism was like “putting a stone on a nation’s feet,” hampering development. After a century of colonial humiliation, invasions and destruction, it is a lesson that China will not forget and that is only too familiar to many nations in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

What China seeks is peace and stability for economic development.

The original was released by China.org, China’s official government portal on October 2, 2015.

Too optimistic and too benevolent on the Beijing regime’s true intentions (domestic, regional and global). It is far from true that China and US have mended fences on the SCS, where Beijing’s blatant expansionism is a major threat to regional stability