New Movements Of Extremism In South Asia And Role Of Sufi Ulama – Analysis

Asia-Pacific countries, where most of the world’s Muslims live, are today an appropriate place to examine Islamic Movements’ status and direction. Across the region, in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, domestic social, religious and political dynamics are highlighting the possible future role of Islam. The purpose of this paper is to assess the current and likely future role of Islamic organizations, movements and Muslim political wings in key countries of the Asia-Pacific region. In particular, the paper is focused on India and Pakistan, particular and South Asia in general, including Bangladesh, Maldives, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines.

Introduction

Asia-Pacific countries, where most of the world’s Muslims live, are today an appropriate place to examine Islamic Movements’ status and direction. Across the region, in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, domestic social, religious and political dynamics are highlighting the possible future role of Islam. While there are significant historical and current differences in the role played by Islam in these countries, each of these countries is to a greater or lesser extent searching for an accommodation involving organized Islam.

The following is a brief overview of some key facts, figures and findings detailing Islam’s implications for Asia-Pacific countries in general and South Asia in particular:

Compatibility of the faith with democracy

A major debate within the Islamic community in Asia-Pacific countries is the compatibility of the faith with democracy. Muslims certainly participate in democracies (e.g., India and Pakistan) and Islamic movements are playing a role in possible transitions to democracy (e.g., Indonesia). In essence, at least in practical as opposed to theological or philosophical terms, Islam and democracy are not incompatible. One of many complexities of this debate is the different attitudes of Sunnis and Wahhabis toward democracy.

Islam and the Militaries

The role of Islam in the militaries of the Asia-Pacific countries represented at the meeting obviously differed considerably. In Indonesia, for example, it was noted that while the military has long had uneasy relations with Islamic political parties and movements, this relationship is less troubled today. Regarding Pakistan, concern was expressed that lower and middle level officers were becoming more supportive of Islamic groups.

Islam and Security

Islam’s implications for security in Asia-Pacific region at the national or country level come in the form of political stability and ability to accommodate minorities where Islam is the majority religion. At the regional level, Islam’s role in security appears to be its relevance to either promoting cooperation or creating tensions. At the international level, a major issue is Asian Islam’s role in international Islamic movements and organizations particularly relations with the Middle East. At none of these levels (national, regional or international) does Islam in Asia pose a serious or immediate security problem. Only in South Asia, given Islam’s growing role in Pakistan’s domestic politics and its response to Hindu nationalism, is Islam a major element affecting both domestic and regional security. Longer-term issues include the restiveness of some of China’s Muslims and the shifting social, economic and political roles of Islam in Malaysia and Indonesia.

New Movements of Thought South Asian Muslim societies

As stated earlier, the paper is focused on new movements of thoughts in South Asian Muslim societies, including Bangladesh, Maldives, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines. We will seek to assess the current and likely future role of Islamic organizations, movements and Muslim political wings in key countries of the region.

South Asian Muslims constitute one-third of the worldwide Muslim population, to the wider history of Muslim societies. But, regrettably, the current focus on Islam has concentrated mainly on the Middle East, often neglecting the significant contributions rendered by South Asian Islamic scholars and their movements.

It is highly important to trace back the history of Islam and Muslims in South Asia to illustrate the gradual progression of new Islamic movements of thought over the past several decades. There are several major organisations and movements that have emerged in this period.

Advent of Islam in South Asia: The Role of Sufism

It goes beyond saying that Asia has been a diverse region and Islam has been professed and practiced in different forms, meanings and implications across its breadth. However, there is neither a monolithic Asia nor a monolithic Islam. The many schisms in Islam in South Asia emanate from doctrinal issues (e.g. Sufi vs. Wahhabi), history (e.g., maritime vs. land arrival of Islam), demographics (e.g., minority vs. majority Islam) and political ideology (e.g., secular states vs. religious-proclaimed states).

Islam emerged in South Asia as the spiritual legacy of the Muslim mystics and Sufis, much in the same way as Sanatan Dharma was spread by the rishi-munis. Islamic mystics and Sufi saints of India stood for the unity of existence (Wahdatul Wujud), universal brotherhood (Ukhuwat-e-Insani) and a deeper personal relationship with God (Wisal-e-Ilahi). All these inclusive and tolerant Sufi teachings hold vital relevance for contemporary debates on religious tolerance and pluralism. With the advent of Islam and the Muslims, the peoples of South Asia encountered for the first time a large-scale influx of bearers of a highly advanced, rapidly emerging and sophisticated civilization as well as a peaceful, pluralistic, harmonious and composite culture inspired by spiritually inclined narrative of Islam.

Their faith was open, tolerant, and inclusive of one and all. Islam came in South Asia as a beautiful spiritual doctrinaire committed to the worship of a single, transcendent God (Allah) and infinite love for the Prophet Muhmmad (peace be upon him). The early South Asian Muslims were all deeply inspired by the egalitarianism of Islam, which proclaimed all believers equal in the sight of God.

From the 11th century, Islam became a major force in the South Asian history. Muslims added further layers of richness and complexity to Indian civilization and some of its most enduring channels to the peoples and cultures of South Asian lands.

Right from the beginning, Sufi inspiration was widespread in the South Asia. For instance, there was a great Sufi saint namely, Hazrat Shahul Hamid Nagori (1504–1570), popularly known as “Qadir Wali” because of his power to protect seafarers and others who sought his aid. His vast shrine on the coast south of Madras, draws not only local pilgrims but also others from Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and beyond, where Tamil Muslims have carried his tradition. (A Historical Overview of Islam in South Asia- Barbara D. Metcalf)

The Muslim rulers also subscribed to the same narrative of peace and pluralism. For instance, the most prominent Muslim ruler of India, Mahmud Ghaznavi gave patronage to produce major works on Sufism such as Firdausi’s great Persian epic, the Shahnama and the scientific work of al-Biruni (973–1048). The first Persian text on Sufism in the subcontinent was the Kashf al-Mahjub (The Disclosure of the Hidden) of Hazrat Shaikh Abul Hasan ‘Ali Hujwiri (d. 1071), written in Ghaznavid Lahore, which became a major source for early Sufi thought and practice. Shaikh Hujwiri’s tomb in Lahore stands today as one of the major Sufi shrines of the subcontinent.

The writings of the great scientist, traveler, and writer known as al-Biruni encompass scientific, ethnographic, and philosophical subjects, in contrast to the devotional topics that typically hold pride of place for this era. Al-Biruni visited many of the towns of northwestern India and wrote an encyclopedic work on the history, religion, and sciences of the region. He was a remarkable scholar whose work on geography, astronomy, and comparative religion was innovative and wide-ranging. (A Historical Overview of Islam in South Asia- Barbara D. Metcalf)

Islam and Muslims in South Asia Today

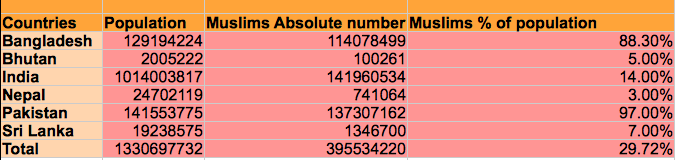

South Asia comprises the largest concentration of Muslims in the world, with over 395 million people professing Islam as their Faith. Indeed, India has the second largest population of Muslims – after Indonesia – for any country: nearly 142 million.

South Asia is home to the second, third, and fourth largest Islamic countries in the world. Roughly 400 million Muslims live in the region though the distribution varies greatly; for example, there are some 300,000 Muslims in the Maldives and 137.7 million in India. Indeed, India’s Muslim population, though only about 14% of its total, is larger than that of the two declared Islamic countries in the region, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A useful way of considering the security implications or aspects of Islam in the subcontinent is to take a national, regional and international approach to the analysis.

South Asia is home to the second, third, and fourth largest Islamic countries in the world. Roughly 400 million Muslims live in the region though the distribution varies greatly; for example, there are some 300,000 Muslims in the Maldives and 137.7 million in India. Indeed, India’s Muslim population, though only about 14% of its total, is larger than that of the two declared Islamic countries in the region, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A useful way of considering the security implications or aspects of Islam in the subcontinent is to take a national, regional and international approach to the analysis.

The way in which Islam spread in South Asia has been highly important. Contrary to the view that Islam was spread in the subcontinent by Islamic conquerors, in fact it spread through the preaching of Muslim Sufi saints. The Sufis practice a type of Islam that contrasts with the more conservative styles and values prevalent in the conservative and radical societies in the Middle East and even Afghanistan.

Muslim Sects in In South Asia

In South Asia, the indigenous social and religious practices were more amenable to a “softer” kind of Islam. Indeed, nearly 85% of South Asia’s Sunni Muslims are said to follow the Sunni Sufi school of thought. The remaining 15% follow the Wahhabi/Deobandi/Ahle Hadisi/Jamat-e-Islami sects, more closely related to the conservative practice of Islam. Most Shiites in the subcontinent also tend to be influenced by the Sufi thoughts.

Islam at the National Level in South Asia

At the national or country-level in South Asia, Islam has an important impact on political stability. In the case of India, the most compelling domestic security issue is the prospect of widespread and destabilizing Hindu-Muslim violence.[3] India is an extraordinarily diverse country. There are schisms of every kind; religion, ethnicity and language. But the Hindu-Muslim division is really the only one that could rip apart the entire country. One reason for this is that Muslims are not confined to just one part of India. They live among the Hindu majority throughout the country. Moreover, Muslims tend to be concentrated in urban centers, constituting up to a third or fourth of the populations of major cities in all parts of India. It is empirically true that Hindu-Muslim violence has been on the rise since the late 1970s. During the period between 1950 (after the bloody Partition when India and Pakistan became independent in 1947) and 1977, there was a relatively low and stable rate of violence between the two communities.

The growth in Hindu-Muslim violence since the late 1970s is worrying, but so far it has been contained to local violence concentrated in specific places, rather than spreading, dangerously, to the national level. Just eight cities in India account for over 50% of total deaths resulting from Hindu-Muslim violence.[4] Preliminary research suggests that where a healthy civil society in which there are inter-communal associations exists, there is less violence between the two communities. As of now, Hindu-Muslim violence appears to be an internal security concern threatening to the entire country.

Islam at the Regional Level in South Asia

At the regional level in South Asia, there is one issue in which the role of Islam may be considered to have implications for security. This is of course India-Pakistan relations and specifically the dispute over Kashmir. While the history of Hindu-Muslim relations had a major impact on the creation of two independent states after the British withdrew, today the India-Pakistan dispute has expanded far beyond animosity between Muslims and Hindus. As noted earlier, there are nearly as many Muslims in India as there are in Pakistan. Rather than Islam, the main causes of the India-Pakistan disputes are competing nationalisms and the asymmetries of power between the two states. Similarly, the Kashmir dispute is not about the relationship between Islam and Hinduism but rather an outgrowth of these competing nationalisms. The Hindu-Muslim narrative works as a popularizing mechanism to whip up antagonisms in both countries.

Islam at the International Level in South Asia

South Asian Islam’s relevance to international security rests on its relations with the wider Islamic community. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, given their huge Muslim populations, geographical positions and economic and energy needs, have a great interest in and connection to the wider Islamic world. For South Asia’s Muslim countries, membership in Islamic organizations and relations with other Muslim countries, whether in the Middle East or Asia, have always been seen as important to their foreign and security policies.

Political and Militant Movements in Pakistan and their role in South Asia

Pakistan occupies a unique place in the South Asian Muslim world. It is the only state explicitly established in the name of Islam, and yet fifty years after its independence, the role and place of Islam in the country remains unresolved. The basic divide regarding the relationship between religion and the state pits those who see the existence of Pakistan as necessary to protect the social, political and economic rights of Muslims, and those who see it as an Islamic religious state. During the past fifty years, the public has resoundingly rejected Islamic political parties in every general election.

Pakistan over the past fifty plus years has rejected the option of becoming a fundamentalist Islamic state. However, there are signs that the hand of the extremist or conservative elements may be growing stronger. Recently, in parts of certain Pakistani provinces such as the Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP), the extremist Islamists have pressed for the application of Islamic Shariah law. The central government is seen by some as having caved into these pressures. At the same time, the government has tried to counter the extremist trend by itself amending the constitution to introduce more Islamic laws. This attempt to undermine more extremist demands may actually backfire, if the Islamic movement interprets the government’s move as a sign of weakness.

Sufism in South Asia Today

Sufi saints disseminated their pluralistic messages in the Indian subcontinent at a time when the idea of religious tolerance was not even debated in a large part of Western Europe. They laid greater emphasis on the broader Qur’anic notion of wasatiyyah (moderation in life) maintaining a moderate narrative of Islam. It exhorts man not to transgress the limits determined by God. Since the Sufi saints practiced this spiritual Islamic principle in its entirety, they shunned all forms of extremism (tatarruf), harshness (tanattu), violence (tashaddud) and exaggeration (ghuloow) not only in matters of faith, but in all walks of life. They believed that spirituality is a luminous and universal body of truths that wins the hearts. However, they strongly disagreed with the practices of subjecting spirituality to any narrow interpretation of religion. They rather advocated the universal values of religion that reach the minds and the hearts of people beyond man-made distinctions’. Thus, they found the solution to human problems both of material and spiritual nature, in their spiritual reading of Islam.

Indian Sufi saints inspired a huge following by their theory of sulh-e-kul (peace for all), a Sufi term that essentially means: love for all and hatred for none. This greatly impacted their attitude towards other faith traditions. Indian Sufis were keen to share commonalities with adherents of other faith traditions they encountered in the subcontinent, notably the yogis and the mystics of the Vaishnav tradition, both influential in this land of age-old Vedic tradition. Their liberalism was beautifully reflected in their halqas (sessions) of harmonious Sufi music or the sima, against the vehement opposition from the orthodox ulema. Since the Sufis were practitioners of the spiritual doctrine of Wahdatul Wujud (the unity of existence), they strongly believed that the light of God is present in all creations and, thus, taught their followers to respect people of all faith traditions.

As a result, they were loved and admired by all and sundry. People of all caste and creed, faith and tradition were equally inspired by the immense sincerity and simplicity in the lives of these mystically-inclined saints. Imbued with the lofty mystical experiences, Indian Sufis lived by the Prophet’s ideals of simple living. They renounced the extravagant and wasteful aspects of life and followed the higher humane ideals in an effort to serve humanity at large. They also exhorted their followers to live by the same ideals, leaving behind glorious examples for others to emulate. The very spiritual epithet “Sufi” is literally driven form the Arabic word “Suf” meaning wool, the preferred clothing of Sufis. They used to shun attractive clothes made of silk and other fineries. But this line of thinking was not an outcome of any ascetic approach of life. They were, rather, inspired by the Qur’anic exhortation that unveiled the deception rooted in the life of the glamorous world.

What actually appealed to all Indian peoples, regardless of caste and creed, was the Sufis’ spiritual legacy of humanism and social activism. The Sufi saints of India combined their mystical search with a spirit of social service. It was upheld by their shrines and khanqas running across the country as seminaries (madrasas) of mystical learning, experience and enlightenment. The curriculums of those madrasas were so broad and inclusive in their worldview that students and disciples from all backgrounds were cordially welcomed. Devotional songs were composed there in different vernacular languages and Sufi music (sima’) was considered a manifestation of complete submission to God.

The great Sufi saint who had a fair share in preaching Sufism in India was Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti of Ajmer, who left his abode, Herat in Afghanistan, in search of higher spiritual learning and experience. Having visited the central Islamic seminaries his time, travelling all across Central Asia to the Middle East, Khwaja sahib attained solace in India. He gave a definite turn to the Sufi narrative of Islam by introducing the element of ecstasy and the mystic doctrine of the immanence of God. Inspired by the early Sufi masters, notably Khwaja Usman Haruni, he focused on the loving devotion to God, discipline of the individual soul and brotherhood of mankind. Consequently, his mystical mission fostered amicable understanding between Muslims and non-Muslims. At a time when India was struggling to rise above the differentiators of cast and creed, the Sufia-e-Kiram stressed on the essential Qur’anic message of equality and prophetic saying that “All mankind is one family of a God”.

Thus, one of the most glorious impacts of Sufi saints on Indian society was the widespread phenomenon of social integration between common Muslims and non-Muslims. Even many non-Muslim brethren, particularly Hindus and Sikhs, chose to become Murid (disciples) of Sufi saints. It was the mystical impact of Sufism on composite Indian culture and society that inspired the Bhakti movement in southern India first and then in northern India. Even Sikhism preached by Guru Nanak was highly inspired by Islamic mysticism (tasawwuf) due to its emphasis on monotheism and rejection of caste system and idol worship. However, among all the mystical movements and spiritual interpretations of different faith traditions, the common cause was the stiff opposition to the priestly domination and obsession with false rituals and dogmas.

Sufis espoused one of the foundational principles enshrined in Islam: freedom of religion. They maintained and encouraged the view that coercion in matters of religion goes against the spirit of every religion. They believed that the true believer is truly free. That is to say, freedom is increased to the degree belief is strengthened. The notion of freedom was so endeared by the Sufi saints that a Turkish Sufi, Saeed Nursi described it as the most important principle in life. He proclaimed: “My freedom, which I am most in need of, is the most important principle in my life. I can live without bread, but I can’t live without freedom.” It is also gratifying to note that the Indian Sufi saints encouraged the rationalist and non-conformist elements in society. For instance, Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia followed an inquiry on the laws of movement, which displayed a remarkable degree of empirical thought.

Writing at the turn of the 13th century, Amir Khusro was just one of many Sufi saints to espouse the notion of love as the ultimate human emotion – the essence of one’s connection with Allah. From Al Ghazali to Rumi, Hafez to Bulleh Shah, sufism has had an impact on the practice of Islam across the Muslim world throughout the centuries.

The teachings of such saints have been revered as seminal interpretations of the essence of Islam and of the Qur’an itself: the Divan-e-Hafez, for example, is present in almost all Iranian households.

Columbia University recently hosted a conference, ‘Sufism in India and Pakistan: Rethinking Islam, Democracy and Identity’, in order to better understand the ‘role’ that sufism plays in South Asian identity politics. Some of the west’s most esteemed academics on Islam and South Asia presented papers on a wide-array of subjects – from barelvis in Pakistan to inter-religious relations at Delhi’s Firoz Shah Kotla dargaah. Academics discussed and debated the various meanings and interpretations of sufism across the Subcontinent at the theological and political levels, concluding that sufism is somehow more conducive to modern secular beliefs.

New Movements of Extremist Thoughts among South Asia’s Muslims:

Across South Asia, there has been a wave of radical movements, which sometimes turn militant, whose source can be traced to the Wahhabi movement. What is this movement and how did it spread throughout the Muslim world, and now the Western world? What are its ideological differences with traditional spiritual and mystical Islam and how are these differences influencing and supporting modern day radical movements? What can be done to diminish the power of these movements in vulnerable states?

Mainstream spiritual Islam considers faith as a personal relationship between man and God. Therefore, in this spiritual belief, there can be no compulsion or force used in religion. From the time of the Prophet Muhammad (saw), peace and tolerance were practiced between different religious groups, with respect to distinctions in belief. Contrary to this, the “Wahhabi” ideology, which is built on the concept of political enforcement of religious beliefs, thus permit no freedom in faith.

The origins of nearly all of the 20th century’s Islamic extremist movements lie in a new Islamic theology and ideology developed in the 18th and 19th centuries in tribal areas of the eastern Arabian Peninsula. The source of this new movement of thought was the 18th century Muslim scholar named Muhammad ibn Abd-al Wahhab. Thus, his cult was named “Wahhabism.”

It must say in the strongest terms that Sufism, the heart of Islam, is today under continued attack in every concentration of Muslim populations throughout South Asia. There is a deep and penetrating radicalisation of Islamic beliefs that may drive Muslims in general to an extremist cult in times to come. Islamophobia is vehemently denounced, both by moderate scholars and the apologists for extremists alike. But there is a neglect of a vicious process of the xenophobia against all other religions and nations among the extremist followers of Islam – Wahhabis/Salafis/Ahle-Hadisis/Jamate-Islamis.

There is a complete ideology of hatred, intolerance, xenophobia, violent extremism and exclusivism, which is fervently propagated by the radical followers of Islam, particularly in the petro-dollar-funded madrassas, religious schools and seminaries that are preaching a hardcore version of faith in the name of Islam in different South Asian countries. This fatal ideology has captivated the minds of many ardent Muslim youths and new converts.

Although the extremists are still a minority in South Asian Muslim societies; but they are well funded, energized, armed and extremely hardocore and a growing minority. On the contorary, the mainstream Sunni Sufi Muslims have tended to silence, passivity and conciliation. There is little courage of conviction or the will for any moderate Islamic resistance in order to tackle the onslaught of extremists among Muslims.

Sufi Ulama & Mashaikh Tackle The Onslaught Of New Extremist Movements in South Asia

Sufi Ulama, Mashaikh, Imams and muftis from Morocco to India to Bosnia to Chechnya to Pakistan to UAE to war-torn Syria –including Shia coumminity, are have come out to tackle the onslaught of religious extremism. Thus far, many Sufi Islamic scholars and clerics and their organisations have held back the tide of Wahhabi extremism and radicalism. Amongh these South Asian Muslim organisations and thinkers who are articulating an Islam-based approach to peace and de-radicalization are—for instance, the Pakistani Sufi scholar Dr. Tahirul Qadri and his Minhajul Qur’an International, the South-Indian Sufi scholar Shaikh Abu Bakr Ahmad and his organisation, All India Muslim Scholars and the apex body of Sunni Sufi Muslims, All Inida Ulama & Mashaikh Board. These Sufi Muslim thinkers and organisations are actively engaged in research and activism for peace and de-radicalisation in the Muslim world.

The Role of An Apex Body Of Muslims, Ulama & Mashaikh Board (AIUMB) In India: An Example

This was the first time an Indian Sufi Sunni apex body of Muslims, Ulama & Mashaikh Board (AIUMB) had gathered millions of mainstream Muslims and intellectually demolished the ideology and theology of Al Qaeda and like-minded groups. The misguiding ideas of takfir, jihad, governing by Sharia, al wala wa al bara (loyalty to Muslims and disavowal of others), religious classification of non-Muslim countries and war were all scrutinized. This conference illustrated that mainstream Sufi-Sunni Muslims have the beautiful spiritual ideas, arguments and energetic drive to eradicate the cancer of extremism and intolerance in the name of Islam. However, one conference is not enough. We need a much larger platform to contain the dangers of the extremists’ movements. Keeping this in view is going to organize an international Sufi conference or Religious Leaders’ Summit in the beginning of next year (2016).

In recent years, this Sufi-oriented Muslim organization has organized large-scale conferences (what they called “Muslim Maha Panchayats”), besides small gatherings, in many parts of India, in an effort to awaken the country’s Muslims. These efforts of Sufi Sunni Muslims, who constitute around 80% of total Muslim population in India, have also been endorsed by the Indian Shias in their resolutions, which have duly been forwarded to governmental authorities. In these gatherings, Sunni Sufis have declared that they accept neither the Imamat (religious leadership) nor the Qayadat (political leadership) of the extremist Wahhabis.

As a result of such efforts, radical preachers and televangelists like Dr. Zakir Naik faced strong and spirited protest from mainstream Indian Muslims. Dr. Naik, who is President of the Mumbai-based Islamic Research Foundation and a frequent public speaker in Muslim countries, organized a public lecture on January 17, 2015 at the India Islamic Cultural Centre (IICC), New Delhi. A large number of mainstream Muslims, both Sunnis and Shias, gathered outside the premises of the IICC, strongly protesting against his address at the venue. They held that Dr. Naik had not only hurt the sentiments of Shia and Sunni-Sufi Muslims and non-Muslims, but had also desecrated the values of religious harmony and respect for all faiths. Therefore, they did not think it appropriate for Dr. Naik to be a guest-speaker at the IICC, which is meant to stand for communal harmony and amity amongst the people of India.

Recently, in a continued effort to reaffirm their stated position, mainstream Indian Muslims organized a mass protest in a peaceful and democratic manner to demonstrate their anger against the impending dangers of the extremist Wahhabi preachers, particularly Yusuf al-Qaradawi. This widely-known Mufti had sought to justify suicide-bombing by so-called jihadists in his Fatwas. Al-Qaradawi continues to enjoy worldwide exposure via Al-Jazeera television, through his weekly program “Sharia and Life” (al-Shari’a wal-Hayat).

Today, many South Asian Muslims are alarmed about radical preachers funded by Saudi/Qatari patrons. However, few of them are ready so far to recognize the violent extremist content in al-Qaradawi’s literature. At a time when the Egyptian government has banned radical literature penned by Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Sayyed Qutb and Hasan al-Banna, one would be amazed at Indian Muslims’ naivety if they do not shun the same.

It is about time Muslims the world over as well as their governments emulate the de-radicalisation efforts of Egypt, Chechnya, Bangladesh and Kazakhstan. These states have banned radical Islamism and Wahhabism in all its forms, particularly in mosques, madrasas and in the school curricula. They have replaced radical Wahhabi imams with peace-loving and moderate ones, with the aim to restore peace and curb extremism.

Most importantly, the oldest Sunni-Sufi Islamic educational institution, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, has denounced the Wahhabi ideology of radicalism. The head of Al-Azhar, Ahmad al-Tayeb, declared the Wahhabis’ corrupt interpretation of Islam to be the root cause of violent extremism in the Muslim world.

Conclusion:

An ideology of hatred and terror can only be countered by an ideology of love and peace. Sufi Islamic scholars and preachers can play a proactive role in countering extremist discourses and promoting progressive and moderate ones. Although civil society activists also have an important role to cover this area, Ulema and other religious scholars can best work out strategies to control extremists’ preaching. First and foremost, they must exhort their youths not to leave doors open to any religious preacher trying to fill their minds with hate-filled sermons. The state also has an important responsibility in preventing radical preachers from spreading their nefarious influence.

*Ghulam Rasool Dehlvi is a classical Islamic scholar, English-Arabic-Urdu writer, and a Doctoral Research Scholar, Centre for Culture, Media & Governance (JMI Central University). After graduation in Arabic (Hons.), he has done his M. A. in Comparative Religions & Civilizations and a double M.A. in Islamic Studies from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. He can be contacted at [email protected]