Women, Gender And Think Tanks: Political Influence Network In Twitter 2018 – Analysis

What are the relationships and networks of gender studies and women specialists within the global network of political influence on Twitter?

By Cristina Manzano and Juan A. Sánchez-Giménez*

The presence of women in think tanks is still lower than that of men but, in addition, female influencers seem to be less influential in Twitter than their male counterparts. In addition, gender studies are hardly taken into account in the different fields of the analysis of international relations.

During 2018 we have monitored the network of relationships of the world’s leading think tanks and some of its analysts and have added a small network of gender research centres and activists, and women analysts interested in these issues. Our representation of reality, however, gives rise to certain questions: how large is the female presence in think tanks?; how do gender studies relate to the rest of the international relations field?; and how does the gender focus flow within the network?

Analysis

As Mary Beard describes in Women and Power, women have been taught to remain silent since ancient times. The British scholar brilliantly traces the reason why female voices have traditionally been ignored in the public sphere by recounting how, in ancient Greece, Telemachus, son of Odysseus, orders his mother to remain silent because ‘speech will be the business of men’. According to Beard,

‘… it is a nice demonstration that right where written evidence for Western culture starts, women’s voices are not being heard in the public sphere. More than that, as Homer has it, an integral part of growing up, as a man, is learning to take control of public utterance and to silence the female of the species.’1

Quite a few centuries later, the presence of women in the public debate, despite significant progress in the past few decades, is still limited. This has a direct impact on their visibility, which, in turn, relates directly to their capacity to exert influence. The situation is more than evident even in disciplines in which women outnumber men.

Journalism is one of them. There are more women in schools of journalism and newsrooms than ever. In Spain, for instance, women account for 60% of Information Science students and half the staff of most media outlets. However, they only hold 10.9% of the leading positions in printed media and a slim 3.9% in digital media; when it comes to their role as columnists and opinion-makers, only 21% of the opinion pieces in the Spanish press are written by women. These figures are not very different from the European average of 23%.

It is similar in the academic realm: more than half the students in Spanish universities, around 40% of lecturers and 21% of professors are women. However, the higher the position, the smaller the number of women, with only 20% of deans being female.

The think-tanks world is no exception. When Anne-Marie Slaughter (@SlaughterAM) became the head of the New American Foundation in 2013, only seven of the 50 most important think tanks in the US were run by women according to Foreign Policy Magazine. In Spain, there has never been one.

A good number of surveys and reports show that women are less cited in academic papers than their male counterparts. Dion, Sumner & Mitchell, for example, show that ‘Accumulated evidence identifies discernible gender gaps across many dimensions of professional academic careers including salaries, publication rates, journal placement, career progress, and academic service and recent work in political science also reveals gender gaps in citations, with articles written by men citing work by other male scholars more often than work by female scholars’.2

Similarly, Maliniak, Powers & Walker, who have studied the specific case of International Relations, find that ‘Research produced by a woman will be read less and cited less than research produced by a man. Not only does this mean that the trajectory of intellectual developments will be slower than it should be, but it means that the types of topics and methods being showcased in journals and on syllabi are likely to be skewed toward those favoured and pursued by men’.3

One of the significant reasons the authors identify for their findings is that women tend to cite themselves less than men, which clearly has an impact on their capacity to be more cited by others.

A few years ago, various movements started to claim a greater presence of women in expert panels. Several well-known authors ‘rebelled’ against the lack of women at the annual World Economic Forum at Davos. Others, like Owen Barder, Director for Europe of the Center for Global Development, set up initiatives such as ‘The pledge’, inviting the expert community not to take part in events without women; many others followed. Lists of female experts have also been collected extensively. A pioneer case was Hay mujeres, a Chilean foundation which offers advice and training for expert women to appear in the media. More recently, in 2018, the office of the European Parliament in Spain launched the initiative #DóndeEstánEllas (‘Where are the women?’) with a similar intention.

The number of women in politics varies enormously from country to country and is not covered here. The introduction of quotas and laws to guarantee a significant presence of women in national parliaments and governments has been critical to improving figures in this respect. The Spanish Parliament, with more than 40% of women among its members, is one of the countries with the largest percentage, behind only Sweden and Finland.

But returning to our topic, be it in the academic realm, in the world of experts or in politics, the link between visibility and influence seems more than obvious: in order to achieve the latter, experts need to make their voices heard.

Over the past decade, Twitter has become a forum where political ideas and influence have found a new channel and new forms of expression. How think tanks behave and relate amongst themselves and with other actors in the new digital arena has been the scope of different pieces of research by the Elcano Royal Institute in previous years.

In such an exercise, together with the papers by the Elcano Royal Institute, the online magazine esglobal published a special dossier that includes two rankings: one with the most influential think tanks and one with the most influential think-tanks experts in Twitter.

In 2018 a Twitter conversation was initiated about the small number of women in the latter ranking, generating a good number of interactions. That conversation is the starting point of this paper. This time the focus of research is therefore twofold: on the one hand, the place, relations and networks of female think-tank experts in Twitter; on the other, the relationships and networks of gender studies and specialists within the global network of political influence in that universe.

The global think-tank network

At the beginning of the 21st century, the number of think tanks increased significantly worldwide, especially in the US. Think tanks are research and analysis-oriented organisations in the fields of international relations and public policies whose aim is to influence different players who intervene in decision-making processes. Influence, presence and power are all concepts used in the analysis of international relations. Unlike presence and power, however, influence needs to generate trends through ideas or ideology.

In that respect, we designed our political influence network of think tanks in Twitter following the one published in 2015 by Manfredi, Sánchez & Pizarro.4 We have added to that network a number of researchers and analysts linked to different institutions, since they help to disseminate and to strengthen the political message beyond the political realm.

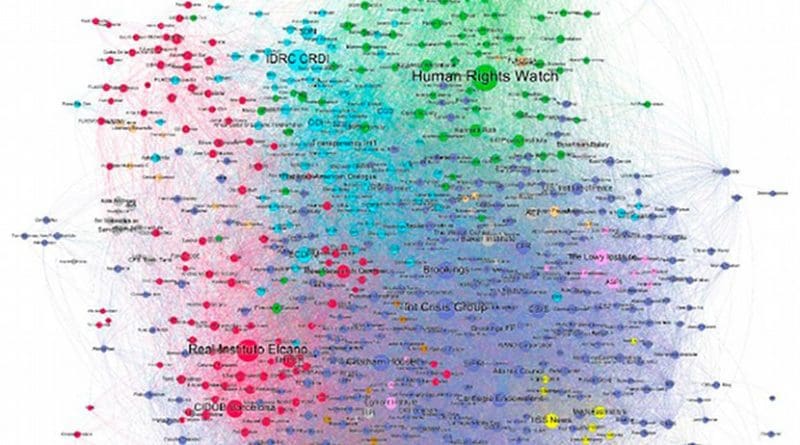

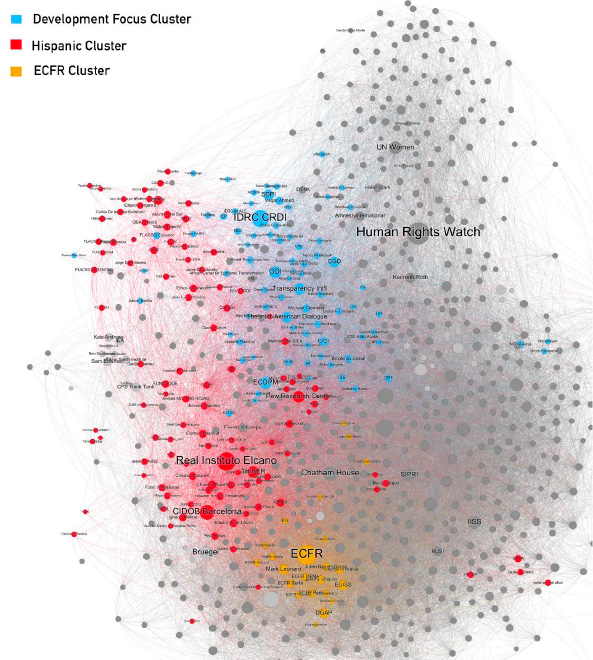

The resulting network comprises 799 active Twitter accounts of think tanks and think-tank experts and analysts (Figure 1).

Having framed our network as the context in which we observe political influence in Twitter, we have gathered activity data for three specific periods along the course of 2018: March, August and November. The result is a total of 284,700 relationships, of which 248,033 are tweets, retweets, mentions and conversations (replies). The other 36,667 correspond to Twitter interactions that took place before 2018 and 2017. The bulk of the activity measured (87.12%) can thus be dated throughout 2018 and be used to draw the relationship map of that year.

In our network of influencers in Twitter (Figure 1), which has become our representation of reality, how large is the female presence?, what kinds of relationships between men and women are established in a specialised network such as this?, how do gender studies relate to the rest of the international relations field’ and how does the gender focus flow within the network?

Apart from looking at the number and interaction of women in our network, in order to introduce the role of gender in our study we have also added a small network of 15 gender research centres, which include UN Women and specialists in gender issues and international relations. This will allow us to analyse the behaviour of gender studies in the larger network as well as the gender gaps that emerge in international relations and area studies.

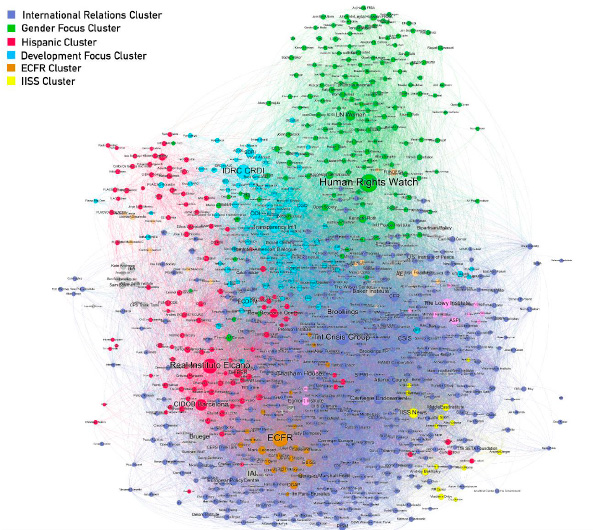

When measuring network modularity, we can see that 92% of the network is distributed in five modules or sub-networks: International Relations, Gender, Development, In Spanish and ECFR. We understand modularity as the ability of a network to be seen as a union of several modules, sub-networks, clusters or communities that interact with each other and shape a common logic within the global network. Each module/cluster has specific and differential features in comparison to other modules/clusters while maintaining its relation to the global network.

Women, gender, think tanks and Twitter

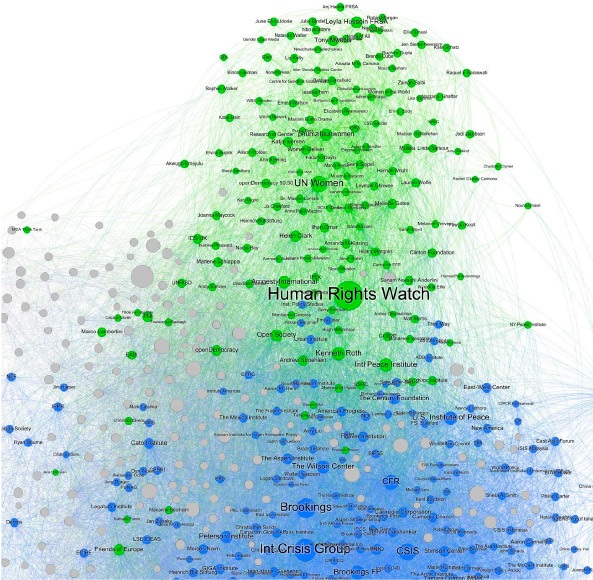

One of the outcomes of including gender as a specific field is that the geographical element –key in previous editions of the study– fades away, while the network becomes more polarised and also more global. This is directly linked to the weight of global influencers such as UN Women, Human Rights Watch (HRW), ECFR and Crisis Group, which become important nodes (Figure 2).

Gender studies appear to be isolated in relation to the other fields of activity within the realm of think tanks. Gender is of interest mostly to gender specialists and perhaps to a few experts and institutions dealing with human rights and development.

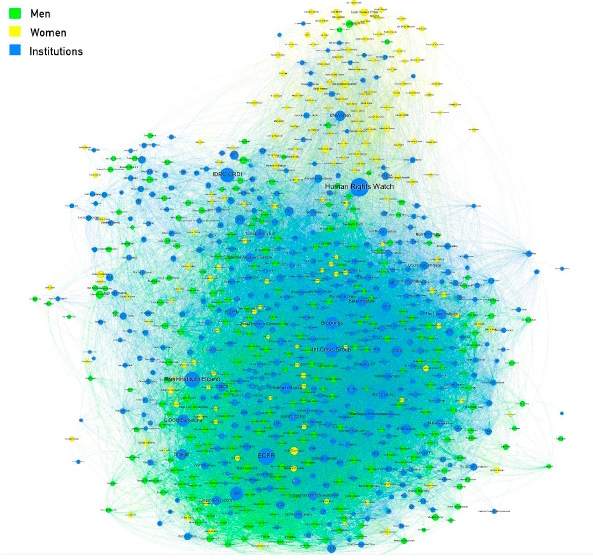

Our on-line global network of political influence reflects a similar proportion of female presence to that seen in other areas in the offline world: it hardly reaches a quarter of the total on average (see Figure 4: 22.03% women, yellow; 32.29% men, green; and 45.71% institutions, blue).

Looking at our Political Women Influencer Network we can see that Women (yellow nodes) are in the majority in the upper part of the graph, dominated by gender studies, development and human rights. Meanwhile, the global cluster is dominated by institutions devoted to International Relations, security issues and the international economy, while female influencers (in yellow) are very scarce at the centre of the graph.

The list of the top 10 women influencers shows a mix between gender specialists and IIRR and area experts: Figure 4. Top 10 women influencers

| Influencer | Institution | Research area | Weighted indegree | |

| Judy Dempsey | @Judy_dempsey | Carnegie Europe | International Relations | 1194 |

| Phumzile Mlambo | @phumzileunwomen | UNWOMEN | Gender | 1038 |

| Leyla Hussein FRSA | @leylahussein | The Girl Generation | Gender | 1036 |

| Helen Clark | @helenclarknz | Former UNDP | Development | 903 |

| Kate Andrews | @kateandrs | Institute of Economic Affairs | International Economy | 870 |

| Florence of Arabia | @florencegaub | EU Institute for Security Studies | Middle East & North Africa | 750 |

| Katja Iversen | @katja_iversen | Women Deliver | Gender | 718 |

| Tamara Cofman Wittes | @tcwittes | Brookings Institute | International Relations | 678 |

| Malala Yousafzai | @malala | Malala Fund | Public Policy | 641 |

| Melinda Gates | @melindagates | Fundación Bill & Melinda Gates | Development | 609 |

Note: the ranking depends of the weighted indegree according to relations. Source: Information & Documentation Service, Elcano Royal Institute.

The weighted indegree is the variable that helps measure and compare influence. The weighted indegree looks at each influencer’s activity as well as at his or her impact on the global network; it varies according to the kind of activity registered by each influencer in Twitter (Follow 1; Tweet 2; Retweet 3; Mention 4; and Reply to 6).

What happens when comparing the level of influence of these women with the list of the top 10 male influencers? (Figure 5) Figure 5. Top 10 male influencers

| Influencer | Institution | Research area | Weighted indegree | |

| Kenneth Roth | @kenroth | @kenroth | International Relations | 1265 |

| Mark Leonard | @markhleonard | ECFR | International Relations | 1258 |

| Sam Bowman | @s8mb | Adam Smith Institute | International Economy | 1033 |

| Andrey Baklitskiy | @baklitskiy | PIR Center – Russia | Security | 967 |

| Charles Grant | @cer_grant | Centre for European Reform | European Issues | 918 |

| Tony Mwebia | @tonymwebia | Women Deliver | Gender | 887 |

| Dmitri Trenin | @dmitritrenin | Carnegie Moscow | Security | 871 |

| Charles Powell | @charlestpowell | Elcano Royal Institute | International Relations | 859 |

| Charles Powell | @sinanulgen1 | @sinanulgen1 | Security | 839 |

| Michael Clemens | @m_clem | Center for Global Development | Development | 836 |

Note: the ranking depends of the weighted indegree according to relations. Source: Information & Documentation Service, Elcano Royal Institute.

The initial impression is that the difference in influence between men and women is relatively small (barely 100 points) considering the larger presence of men in the global network.

However, extending the analysis to the top 100 women and top 100 men, the gap keeps growing: while the women’s weighted indegree is around 480 points, the men’s is at around 622 points.

Female influencers therefore seem to be less influential in Twitter than their male counterparts.

The International Relations/Global Cluster

This cluster covers most of the disciplines that traditionally fall under the international relations label. It accounts for 44.56% of the total network and includes 130 male and 31 female influencers and 195 institutions. Among the women, Judy Dempsey (Carnegie Europe), Tamara Cofman Wittes (Brookings Institution), Jane Kinninmont (Chatham House), Elvire Fabry (Jacques Delors Institute) and Natalie Sambhi (Perth USAsia Centre) stand out, all of them devoted to the analysis of international relations and area studies. Only one is associated with gender issues, Alicia Wittmeyer, the gender editor at The New York Times.

Geographically, this cluster is mostly placed in Europe and the US. Content-wise, foreign policy, international security and international relations at large in the European, US and global arena are the broad areas of work for the experts and institutions included in it. The dominant approach is European but there are also transatlantic and global perspectives.

Despite the majority of the nodes being European, influence lies predominantly in US institutions, especially think tanks with a global reach and working on traditional hard-power issues, which is reflected in the list of the 20 most influential. Washington appears as the undisputed centre for ideas and influence in the US; on the other side of the Atlantic, however, European influence is distributed between different capitals (London, Brussels, Stockholm, Berlin… and, interestingly, Warsaw). Figure 6. Top 20 international-relations cluster influencers

| Influencer | Country | Geographical Scope | Indegree | ||

| 1 | Int Crisis Group | @crisisgroup | US | Global | 3008 |

| 2 | Brookings Institution | @brookingsinst | US | Global | 2503 |

| 3 | Chatham House | @chathamhouse | UK | Global | 2186 |

| 4 | Carnegie Endowment | @carnegieendow | US | Global | 1945 |

| 5 | CSIS | @csis | US | Global | 1942 |

| 6 | SIPRI | @sipriorg | Sweden | Global | 1664 |

| 7 | Council on Foreign Relations | @cfr_org | US | Global | 1609 |

| 8 | European Policy Centre | @epc_eu | Belgium | Europe | 1580 |

| 9 | German Marshall Fund | @gmfus | US | Global | 1551 |

| 10 | Atlantic Council | @atlanticcouncil | US | US | 1446 |

| 11 | Brookings Foreign Policy | @brookingsfp | US | US | 1381 |

| 12 | Carnegie Europe | @ carnegie_europe | Belgium | Europe | 1354 |

| 13 | US Institute of Peace | @usip | US | Global | 1348 |

| 14 | Ifri Paris-Bruxelles | @ifri_ | France | Global | 1340 |

| 15 | Polish Institute of International Affairs | @pism_poland | Poland | Europe | 1313 |

| 16 | The Wilson Center | @ thewilsoncenter | US | US | 1280 |

| 17 | Judy Dempsey | @judy_dempsey | Belgium | Europe | 1194 |

| 18 | RAND Corporation | @ randcorporation | US | US | 1133 |

| 19 | Peterson Institute | @ piie | US | Global | 1105 |

| 20 | SWP Berlin | @swpberlin | Germany | 1050 |

Note: the ranking depends of the weighted indegree according to relations. Source: Information & Documentation Service, Elcano Royal Institute

The narrow link between gender and development

The Gender cluster accounts for 19% of the total network (152 nodes). Most of the influencers are female experts (98) working on gender and public policies. Some of them, though, also work on gender and development.

To identify gender influencers we have applied the same Snowball methodology used to form the global network in 2015. Taking UN Women as the main seed, and adding think tanks as well as analysts and activists in gender issues, we have obtained a small network of 15 think tanks and institutions. None of these organisations is included in James McGann’s Globalgotothinktanks Index in its latest edition (2018). Throughout the ranking there are only two think tanks focused on gender issues: the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), in the US; and the Center of Arab Women for Training and Research, in Egypt, which does not have a Twitter account (and therefore cannot be included in this study).

Why does a survey on political influence experts and think tanks not deliver any results in terms of gender issues? Without a deeper knowledge of the answers to this year’s survey we can only assume two possible reasons: either there are failures in the sample’s composition or the sample is correct but gender is not part of its core interests.

Besides, we would need to know how many women there are among the respondents to the 2018 survey, and how many of them are focused on issues outside the more classic ones in international relations.

The main links of the gender cluster with the rest of the network are HRW and Kenneth Roth (HRW’s Executive Director), who help disseminate both information and influence from this sub-network to the rest.

Other actors in that segment are Open Society, the International Peace Institute and The Institute of Development Studies, together with UN Women; among experts, Helen Clark also plays that role. The profile of institutions and individuals reinforces the assumption of the link between gender and development. These are the influencers who attract the greatest activity within the network (retweets and mentions) too.

Among the 103 influencers in gender studies or policies, Leyla Hussein (FRSA) has the largest ‘betweenness centrality’ (interconnection), only behind UN Women but in front of Joanna Maycock, of the European Women’s Lobby and Katja Iversen, of Women Deliver. Hussein is thus one of the few activists in gender issues that have some influenceover the rest of the network. She brings distant influencers throughout the network closer thanks to her relations with significant think tanks, such as HRW and Women Deliver, and with UN Women.

Her dominant position within the gender cluster increases her global influence beyond that module. Added to that, the content shared by the rest of the global network reaches other gender influencers in a faster way if it reaches Leyla Hussein beforehand, which specially benefits the development and the international relations clusters (Figure 7).

Influence in Spanish

Unlike in the rest of the network, where English is the undisputable leader, in this cluster Spanish is the main language. It includes 108 nodes (13.52% of the total network) with three standing out amongst them: the Real Instituto Elcano (RIE), CIDOB and the Pew Research Center (PRC) –which does not tweet in Spanish but maintains interesting relationships with the cluster–. The main Latin American influencers are also part of this sub-network (see Figure 8).

As for experts, Charles Powell (RIE), Eduard Soler (CIDOB) and Conrad Hackett (PRC) are the most significant nodes in this very institutionalised cluster.

CIDOB and RIE, along with Conrad Hacket (PRC) provide the interconnectivity with the rest of the global network. Women account for a mere 17% of it whereas the gender focus becomes diluted amidst other political issues. In that regard Latin America has traditionally been a nest for projects linking gender and development. There is also a small link with Turkey, due to the regular activity of IEMed, Eduard Soler and Haizam Amirah-Fernández (RIE)

On development

This sub-network (81 nodes, 10% of the global network) includes by and large institutions devoted to research on development in its most classical economic approach, with some also working on global ethics and human rights (Figure 8). The most important node is The International Development Research Center, while the Overseas Development Institute (ODI, London) and the Center for Global Development (Washington) play the role with the rest of the network. Very few women are part of this cluster (14.81% vs 29.63% for men). The most active female expert is Isabelle Ramdoo, of the International Institute for Trade & Sustainable Development, who, however, does not have a significant position in the global network.

Despite the traditional relation between gender and development, as mentioned above, there are no influencers specialised and working on the subject in this group. Most of the institutions, however, include gender with a transversal approach in their research, and some of them have specific departments or specialists among their researchers (although they may not have a significant activity on Twitter).

A network of its own: ECFR

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) constitutes a network on its own in the offline world and in Twitterland too (Figure 8). Devoted to EU foreign policy, it has offices in a good number of European capitals. Most of its researchers and heads of office are very active on Twitter, feeding their relationships as individuals, those of their respective offices and also those of the ECFR network. Other European influencers are interconnected with this module as well.

At the same time, it interconnects –thanks also to the role of Mark Leonard, Director of ECFR– with the larger module of international relations on the one hand, and with the module in Spanish on the other.

This sub-network shows a lack of women –despite ECFR having several significant female researchers– and of gender specialists.

Conclusions

With a few exceptions, female think-tank experts have less influence in Twitter than their male counterparts. One very simple reason may be that the number of women in our data base (comprised by individuals and institutions) includes fewer women than men. Also, that those who have been included generate less interconnections, which, in turn, might be somehow related to the smaller number of women in executive –and therefore more visible– positions in think tanks.

Nevertheless, it can be said that we have feminised our classic global network of political influencers by introducing the small gender network we have identified, despite the continuing existence of gaps in the influence of gender and women in politics even after including the gender presence into our representation of reality.

As the analysis of the weighted indegree shows, except for a very limited number of women at the top of the influencers list, female experts have less influence in the digital world than their male counterparts. Even if Twitter lives as a parallel universe, in this case its patterns seem similar to that of the ‘real’ world.

Another conclusion is that gender studies generate a conversation in Twitter which is almost isolated from the mainstream. Gender issues seem to be of interest mostly to women experts, which, again, follows the same trend as the offline world. The area with which gender specialists are more interconnected is development, reinforcing the common assumption of the traditional links between both fields (aspects such as gender equality and women’s rights being key elements of development policies).

On the other hand, our map shows that gender is not an area of work within the classical analysis of international relations; the gender approach, via gender influencers, only reaches the network through global institutions working on development and human rights.

There is clear room for improvement here for the gender agenda to become part of the global conversation, which may also explain why gender, as a field of study, has not been able to reach larger parts of the expert world or society at large. A more recent trend points to the need to include a gender approach in all other fields of research and disciplines, in a more transversal way.

*About the authors: Cristina Manzano, Director of esglobal | @ManzanoCr and Juan A. Sánchez-Giménez, Head of the Information Service at the Elcano Royal Institute | @Elcano_Juan

Source: This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute

1 Mary Beard (2017), Women & Power: A Manifiesto, Liveright Nort (EPub), London.

2 Michelle L. Dion, Jane Lawrence Sumner & Sara McLaughlin Mitchell (2018), ‘Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields’, Political Analysis, vol. 26, p. 312–327, doi:10.7910/DVN/R7AQT1.

3 Daniel Maliniak, Ryan Powers & Barbara F. Walter (2013), ‘The gender citation gap in international relations’, International Organization, nr 67, p 889-922, doi:10.1017/S0020818313000209.

4 Juan Luis Manfredi-Sánchez, Juan Antonio Sánchez-Giménez & Juan Pizarro-Miranda (2015), “Structural analysis to measure the influence of think tanks’ networks in the digital era”, The Hague Journal of Democracy, nr 10, p. 363-395, doi 10.1163/1871191X-12341320.