Where’s The Beef? House Intelligence Committee Memo Provides Few Answers And Leaves Many Questions – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By George W. Croner*

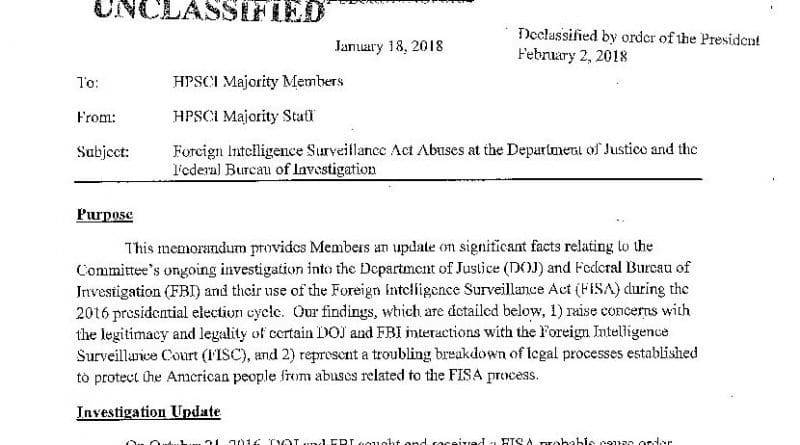

(FPRI) — After touting its content with almost breathless anticipation, the Republican majority of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) last week secured President Donald Trump’s(1)approval to declassify and publicly release the memorandum prepared by the Republican majority’s staff provocatively titled “Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Abuses at the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation” (the “HPSCI Memorandum”). In the end, the HPSCI Memorandum, all three and a half pages of it, revealed little that should impact either the ongoing probe headed by Robert Mueller or the conduct of foreign intelligence surveillance under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

The Extensive Nature of FISC Applications

By law, a significant purpose of every electronic surveillance approved under FISA must be the acquisition of foreign intelligence. FISA is not used for law enforcement; its purpose is to allow the United States to acquire, produce, and disseminate foreign intelligence. Any FISA surveillance directed at a U.S. person requires an order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), and that order is secured through the submission to the FISC of an application. FISA contains extensive requirements for an application,(2)including, among other requisites: (1) the identity of the federal officer making the application; (2) the identity of the target; (3) a statement of the facts relied on by the applicant to conclude that the target of the surveillance is a “foreign power” or an “agent of a foreign power;”(3)(4) a statement of the proposed minimization procedures(4)to be used with the surveillance; (5) a description of the nature of the information sought and the type of communications subjected to surveillance; (6) a summary of the means by which the surveillance will be effected; (7) if applicable, a statement of the facts concerning all previous applications that have been made and the action taken on each previous application; (8) a statement regarding the period of time for which the surveillance is required to be maintained;(5) and (9) a certification (and statement of the basis for the certification) by certain designated senior government executives (defined in FISA) that the information sought is foreign intelligence information, that a significant purpose of the surveillance is to obtain foreign intelligence information, and that such information cannot be reasonably obtained by normal investigative techniques.

The recounting of these FISA application requirements is offered to provide context: context demonstrating that FISA applications are detailed documents, generally consuming 25+ pages of information, and often considerably more. There are no CliffsNotes versions of FISA applications, especially where a U.S. person is the target of the surveillance, and, consequently, despite its efforts at synopsis, the HPSCI Memorandum’s assessment of the FISA surveillance of Carter Page is necessarily incomplete without knowing precisely what was presented to the FISC in the FBI’s applications.

The Necessity of the FISA Application

Lacking those applications complicates any effort to pronounce judgments on the FISA process used with the Page surveillances particularly because FISA mandates a probable cause standard to decide whether to authorize the surveillance. As specified in FISA, the FISC “shall” enter an order approving the surveillance if the court concludes that there is probable cause to believe that the target is an agent of a foreign power and that each of the facilities at which the surveillance is directed is being used by this agent of a foreign power.(6)

Probable cause is a flexible standard that emphasizes common sense requiring a reasonable basis for conclusions based on articulable facts. Probable cause is neither “beyond a reasonable doubt” nor unsubstantiated speculation, but it is predicated on reasonable conclusions drawn from trustworthy facts. FISA specifically provides that, in determining whether or not probable cause exists, the FISC may consider “past activities of the target, as well as facts and circumstances relating to current or future activities of the target.”(7)Although the authors of the HPSCI Memorandum have seen the Page FISA applications, those applications themselves remain highly classified and have not been approved for public release. Only those actual FISA applications provide the full scope of what was presented to the FISC by way of probable cause, and how it was described. Consequently, given the relative flexibility of the probable cause standard and the detail statutorily required in a FISA application, it is speculative to draw conclusions regarding the complete presentation provided to the FISC in the Carter Page FISA applications—and relying on the 3+ pages of partisan distillation of those FISA applications in the Memorandum does not seem conducive to reaching informed judgments regarding the FISA process used to gain FISC approval to surveil Carter Page.

The Role of Carter Page

Caution seems particularly warranted given what the HPSCI Memorandum does reveal about the Page FISA surveillance. What the Memorandum confirms is that the Carter Page FISA process did not initiate the FBI’s counterintelligence probe into Russian election meddling—according to the Memorandum the “trigger” for that investigation was George Papadopoulos talking to a professor linked to the Russians about obtaining political dirt on Hillary Clinton. Based on this Papadopoulos information, an investigation was opened in July 2016, months before the FBI sought the October 2016 FISC approval to surveil Carter Page that is described in the HPSCI Memorandum. While the Memorandum points out that there is “no evidence of any cooperation or conspiracy between Page and Papadopoulus,” there is certainly a connection—they both worked for the Trump campaign at some point in 2016.

Carter Page’s role with the Trump campaign has always been somewhat amorphous. In March 2016, candidate Trump, in an editorial board interview meeting with the Washington Post, listed “Carter Page, PhD” among his foreign policy advisors, but Page had resigned this position by September 2016. The timing may be significant since the HPSCI Memorandum cites to an October 2016 FISC order authorizing surveillance of Page. This suggests that FISA surveillance against Page did not begin until after Page had resigned his position with the Trump campaign, but the Memorandum acknowledges that there were at least four FISA applications submitted regarding the Carter Page surveillance and it is unclear where the October 21, 2016 application falls in this sequence.(8) Consequently, if the October 2016 application is the first seeking an order to surveil Page, then no FISA surveillance was sought against Page until after he resigned from the Trump campaign. However, the more likely chronology suggests that the October 2016 FISA application was not the first directed against Page, and earlier application(s) sought surveillance authority while Page was still “officially” connected with the Trump campaign in some capacity.

Aside from his connection to the Trump campaign, however, there was plenty of information about Carter Page that would pique the FBI’s interest. Page first came to the FBI’s attention in 2013 in connection with a counterintelligence investigation into clandestine intelligence activities conducted by the SVR, the Russian foreign intelligence service. Page had lived in Russia from 2004 through 2007 while working for Merrill Lynch; he conducted business activities and provided consulting services to Russian companies; and, perhaps most significantly, he was talking to Russian “diplomats” who were, in fact, Russian intelligence operatives. Page met at least twice with one of those “diplomats” in particular, Viktor Podobnyy, who the FBI had identified as an SVR operative. Podobnyy operated under diplomatic cover as an attaché to the Russian mission at the United Nations but, as the FBI later charged, was actually an undeclared SVR intelligence officer who, due to his purported diplomatic status, was never tried but was forced to leave the United States. In connection with its 2013 investigation into Podobnyy and other Russian SVR agents, the FBI interviewed Page, but he was never accused of wrongdoing. Later, in July 2016, Page returned to Russia and delivered a speech critical of U.S. policy towards Russia, a trip that, according to the Memorandum, was documented in a September 23, 2016 article by Michael Isikoff appearing in Yahoo News.

All of this was known to the FBI by the fall of 2016 and almost certainly has been documented in one or more, and perhaps all, of the four FISA applications approved by the FISC. However, given the objectives that seem to have motivated the preparation of the HPSCI Memorandum, none of this pertinent information about the life and activities of Carter Page, other than the September 2016 Isikoff article, is mentioned in that Memorandum.

The Memorandum’s Focus on the Steele Dossier

Instead, the Memorandum’s bête noire is the now famous “Steele dossier.” I make no effort here to parse the particulars of that document but, notably, neither does the Memorandum in any productive manner. The focus of the Memorandum is not on what the Steele dossier says, but on who financed Steele’s efforts and Steele’s encounters with the media (including Yahoo News) that, the HPSCI Memorandum insists, “violate[d] the cardinal rule of source handling – maintaining confidentiality – and demonstrated that Steele had become a less than reliable source for the FBI.”

Unmentioned is that Steele did have a prior record of reliability dating back to the FBI’s 2010 investigation of FIFA, the international governing body of soccer. The FBI also knew that Steele’s research had initially been funded by a conservative, Republican-leaning sponsor (i.e., the Washington Free Beacon) before it was adopted by Democratic sources once Trump secured the Republican nomination. Further, the FBI could not help but notice that Steele’s basic information about Russian connections tracked the FBI’s own investigative efforts that already had revealed, for example, Papadopoulos’s disclosures that the Russians were offering “political dirt” on Hillary Clinton, information that the HPSCI Memorandum concedes was also included in the Page FISA application. Moreover, it bears noting that the basic premise of the HPSCI Memorandum—that the FBI disclosed nothing about Steele’s “unreliability” to the FISC—has been refuted in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post, all of which have reported that the October 2016 Page FISA application included information to the FISC that Steele’s work was “politically motivated.”

Consequently, there is ample reason to question what the HPSCI Memorandum says about how Steele’s “reliability” was addressed in the Page FISA applications, but, equally importantly, the Memorandum’s insistence that FISA applications should “include information potentially favorable to the target of the FISA application” mistakenly seeks to graft a law enforcement-type disclosure requirement onto a foreign intelligence mechanism. There is no Brady rule(9) associated with FISA applications because FISA is a foreign intelligence—not a law enforcement—process. Certainly, overt misrepresentation or deliberate concealment of pertinent facts in a FISA application is as unacceptable as it would be in a Title III criminal wiretap application, but there is nothing that requires, or prudently should require, the disclosure of “information potentially favorable to the target of the FISA application.” There is no “defendant” looking at a possible criminal trial in the FISA process, a distinction historically recognized by excluding foreign intelligence and counterintelligence investigations from Department of Justice guidelines applied to the use of confidential informants.

As noted at the outset, without access to the Carter Page FISA applications, it is impossible to undertake an informed analysis of the basis for the FISC’s probable cause conclusions. However, the existence of four separate FISA applications confirms that the FISC found sufficient probable cause to approve the Page surveillance four separate times. FISA specifically contemplates such extensions, but each extension requires “new findings made in the same manner as required for the original order.”(10) Carter Page is a U.S. person, and no FISA surveillances draw more scrutiny or are more rigorously reviewed than those directed at U.S. persons. Consequently, it seems highly unlikely that the FISC would have authorized three extensions of the Page surveillance without the FBI furnishing specific facts demonstrating to the FISC’s satisfaction that the surveillance was, in fact, producing foreign intelligence information as described in the various applications.

If you are a devotee of political conspiracy, then the HPSCI Memorandum is for you, but, it offers no sustenance as meaningful commentary on FISA or the FISA application process—which no doubt explains why the Memorandum fails to articulate any suggested policy changes to correct the “abuses” trumpeted as the “Subject” of its dissertation. Coming as it does from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, this dearth of genuine policy consideration is disappointing—although not surprising in today’s fractious political environment.

About the author:

*George W. Croner, a Senior Fellow at FPRI, previously served as principal litigation counsel in the Office of General Counsel at the National Security Agency. He is also a retired director and shareholder of the law firm of Kohn, Swift & Graf, P.C., where he remains Of Counsel, and is a member of the Association of Former Intelligence Officers.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI

Notes:

(1) The president authorized the Memorandum’s release despite the FBI expressing “grave concerns” about the “accuracy” of the document.

(2) 50 U.S.C. § 1804.

(3) “Foreign power” and “agent of a foreign power” are defined terms in FISA. 50 U.S.C. §1801(a) and (b).

(4) “Minimization procedures” are specific procedures that, in light of the purpose and technique of the particular surveillance, are designed to minimize the acquisition and retention, and prohibit the dissemination, of nonpublicly available information concerning unconsenting U.S. persons consistent with the need of the U.S. to obtain, produce, and disseminate foreign intelligence. 50 U.S.C. § 1801(h).

(5) FISA surveillance orders targeting U.S. persons are limited to the time needed to accomplish the purpose of the surveillance or 90 days, whichever is less. 50 U.S.C. § 1805(d)(1).

(6) 50 U.S.C. § 1805(a).

(7) 50 U.S.C. § 1805(b).

(8) Interestingly, but not specifically acknowledged in the HPSCI Memorandum, the Page FISA applications spanned both the Obama and the Trump administrations. The Memorandum reports that one of the Page applications was signed by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, a Trump appointee.

(9) Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963), is a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that the prosecution has an affirmative duty to turn over all exculpatory evidence to a defendant in a criminal case.

(10) 50 U.S.C. § 1805(d)(2).