Chasing The Historic Traces Of Serbia’s Heroines – Analysis

By Siri Sollie

If you know where to look, testaments to remarkable female pioneers are etched on several locations in urban Serbia.

With International Women’s Day on March 8, Balkan Insight examines the legacy of Serbian heroines immortalised by street names, buildings, statues and memorials throughout Serbia. An observant passer-by will have no trouble spotting the imprints of the women‘s lives and work.

The architectural legacy of Jelisaveta Nacic

In the midst of a sea of male street names in Belgrade, not far from Skadarlija, the bohemian quarter, lies Jelisaveta Nacic Street – named after Serbia’s first female architect.

Jelisaveta Nacic distinguished herself by choosing a different profession and life path from her female peers. She became the first woman to enroll in the Faculty of Architecture of Belgrade in 1896.

Nacic managed to position herself in the typically male-dominated field by designing several notable private and public buildings in Belgrade.

Not too far from her street, one such architectural legacy can be found. Where Cara Dusana Street meets Francuska, the Church of St. Alexander Nevsky stands. Nacic designed the Moravian-style church that was completed in 1929.

The architectural pioneer also took part in the planning of Kalemegdan Park. Connecting the park with the Pariska Street is her neo-Baroque Small Staircase.

Not too far from the staircase, on Kralja Petra Street, you can find one of Nacic’ most remarkable architectural achievements. Belgrade City Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments designated Elementary School King Peter I, located right next to Belgrade Cathedral, a cultural heritage site in 1965.

The broadly neoclassical school, with its decorative art nouveau elements, was considered a highly modern structure that bore no comparison to other school buildings at the time of its construction. Its architectural legacy left Nacic as one of the most indisputably talented and brave architects in Serbia’s modern history.

A forgotten war heroine

If you move out of the city centre and head south to Belgrade’s Vozdovac neighbourhood, you can find Milunka Savic Street. Its name is drawn from the Serbian war heroine who fought in the Balkan Wars and World War I.

In her early twenties, Savic disguised herself as a man and enrolled in the Serbian Army in 1912 under the name Milun Savic. Her identity was first revealed in 1913 after she was wounded in battle and had to be hospitalised. After the incident Savic continued her brave involvement in the Serbian army, where she carved out a reputation for herself as an excellent warrior. Due to her brave involvement she received military honours such as the Russian Cross of St. George and the French Legion of Honour.

On Milunka Savic Street 25 you can find her house still standing at the premises that served as her domicile up until her death in 1973. A memorial plaque was recently placed on the structure in her memory.

In the Novi Pazar Municipality, southwestern Serbia, you can also find a memorial statue that was erected in her honor in her birth village of Koprivnica where the house she grew up in is located.

Impressionist traces in Belgrade and Cacak

You might have noticed the woman at the 200-dinar bill, but did you know that she is internationally recognized as one of the greatest Serbian painters of the 20th century?

Born in 1873 in Cacak, Nadezda Petrovic travelled and worked in France, Germany and Italy over the course of her career, although she constantly returned to her home country. Petrovic was perceived as a modernist by her contemporaries, and her paintings caused controversy among her critics.

Petrovic is also remembered fondly as a great humanist as well as painter, as she volunteered as a paramedic during World War I.

In the center of Cacak you can find a museum dedicated to Petrović that exhibits nearly 400 of her artworks.

The Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments opened a memorial museum dedicated to Nadezda and her brother, avant-garde writer Rastko Petrovic, in Belgrade in 1974.

The museum is located on Ljubomir Stojanovic Street 25, and displays a selection of paintings, letters and items that belonged to Nadezda and her brother.

Two statues have also been erected in her honor, one in Cacak in front of the gymnasium, while the other can be found in Belgrade’s Pioneer Park.

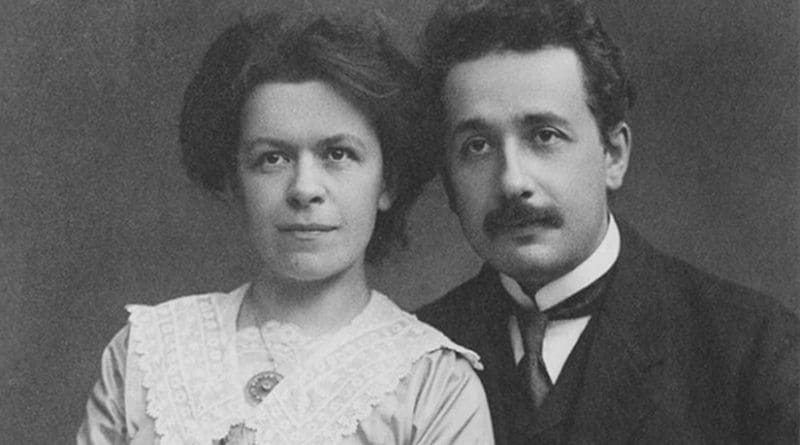

The house of brilliant Mileva Maric-Einstein

Next time you visit Novi Sad, you might want to pass by the family home of Albert Einstein’s first wife and study partner.

Serbian physicist Mileva Maric-Einstein was one of Einstein’s fellow students at the Department of Mathematics and Physics in Zurich in 1896.

Maric-Einstein distinguished herself as the only woman in a group of six at the university. Some academics argue that she was a supportive companion in Einstein’s studies. The marriage lasted until 1919, and the pair had two sons together.

Her family home is located in Kisacka Street 20 in Novi Sad where she spent large parts of her life. Albert Einstein visited on occasion.

Local media report that there are plans to renovate the house by 2021.

Other memorial plaques in her honor have also been placed in Zurich, Sremska Mitrovica and on the Novi Sad University campus.

This article was published in BIRN’s bi-weekly newspaper Belgrade Insight. Here is where to find a copy.