Cameroon’s Anglophone War – Analysis

By IRIN

Emmanuel Freudenthal is the first journalist to spend time with an anglophone armed group, trekking for a week with them in the sun and rain, across rivers and up steep hills, through dark rainforests and fields of giant grass. In this article he explores the make-up and motivation of the Ambazonia Defense Forces, and how the civil war brewing in Cameroon is changing the lives of fighters, civilians, and refugees.

By Emmanuel Freudenthal*

“I killed three of them,” says Abang. “I use this [gun] to kill them like animals, as they are killing me, killed all my brothers.”

Before the army destroyed his village and killed his three brothers, Abang was a farmer and an electrician. Today, he’s one of hundreds of anglophone men fighting with hunting rifles and magical amulets against the US- and French-trained Cameroonian army in an attempt to win independence for a new country they call Ambazonia.

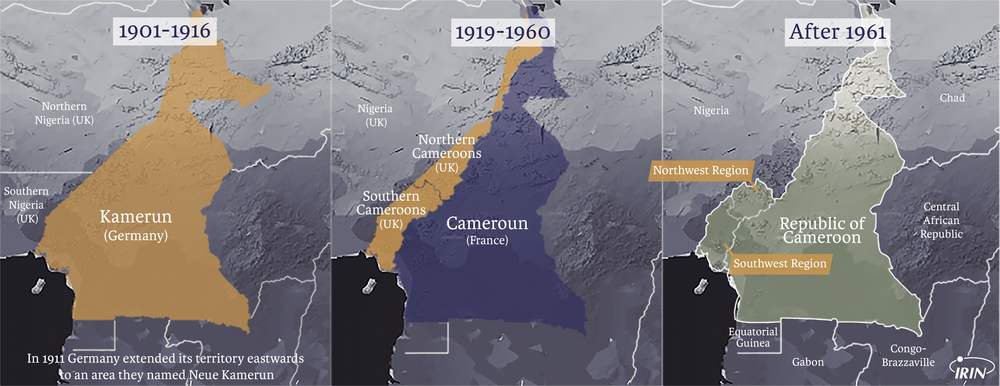

Cameroon’s anglophone minority has been requesting greater autonomy since former territories held by the British and French were federated into one central African nation in 1961. These demands have become steadily more vocal since the 1980s.

In October 2017, peaceful protests – calling for the use of English in courts and classes – took a turn for the worse when security forces killed dozens of demonstrators and jailed hundreds more. This violence led to the birth of several separatist armed groups that have since killed and kidnapped numerous officials in the Northwest Region and the Southwest Region, the two majority anglophone areas. Abang’s group, the Ambazonia Defense Forces, or ADF, is the largest.

More than 180,000 people have been displaced by counter-insurgency operations by Cameroon’s security forces, who have killed civilians and burnt down villages. Most of the fighters interviewed by IRIN joined the militia after they were forced to flee their homes.

In a report published, Amnesty International says separatists have killed at least 44 security forces and attacked 42 schools since February 2017. Some of the attacks on schools were attributed to the Ambazonia Defense Forces by the local population, but Amnesty could not establish that link and a spokesman for the ADF denied the group’s involvement. Amnesty also reported allegations that more than 30 people have been arbitrarily killed by security forces, including a high-profile attack on the village of Dadi in December 2017 in which at least 23 people, including minors, were arrested and then severely tortured.

The government has denied allegations of systematic human rights violations by its security forces. It says it is open to dialogue, but insists that the unity of Cameroon is “non-negotiable.”

Abang, who is in his 30s, is tall and slightly hunches forward when he sits. His friendliness and quick smile disappear only when he talks about the unfairness that drove him to take up arms. Then, his eyes darken and he gesticulates angrily as he talks. He is wearing a black T-shirt – the only top he possesses, he says.

Abang lives in a camp that consists of a few buildings made from mud, a courtyard (that the fighters call the parade ground), and a couple of bamboo poles on which flags are occasionally hung. There are 50 other fighters in the camp.

“Even if they kill me, there is no problem,” explains Abang. “I’m sacrificing my life.”

According to the leader of the Ambazonia Defense Forces, Cho Ayaba, his group has 1,500 active soldiers spread over more than 20 camps throughout anglophone Cameroon.

Over the course of a week, IRIN met combatants from several camps and saw about 100 fighters in total. The ADF appears to be the main armed group operating in anglophone Cameroon. Their equipment is poor – they wear flip-flops rather than combat boots.

Around his neck, Abang carries what he calls, with a smirk, a monkey gun. It’s a hunting rifle made in Nigeria. To load it is cumbersome: you twist a screw under the barrel so the gun snaps open in the middle, push a cartridge inside the chamber, click the rifle back into place, and finally twist the screw to lock it.

Abang carries half a dozen red hunting cartridges tucked into a belt around his waist. He can’t afford more than that. None of the ADF men in Abang’s camp have assault rifles; the entire rebel army appears to have barely a dozen of them.

That’s no match for the assault weapons carried by the soldiers of the Cameroonian army. They have been trained and equipped by France and the United States for their fight against the Islamist extremist group Boko Haram. Their guns spray hundreds of bullet every minute; Abang can perhaps reload once in that time.

Daily life is difficult, Abang says. There’s barely enough space to sleep side by side on the floor of the huts lent to them by the nearby village. There’s not enough food, and the river water that they drink is milky with silt.

For Abang, there’s nowhere else to go. The army destroyed his village, sending his whole family fleeing into the bush, where, he believes, they are still hiding. The military then set up a camp in his village, and now he says he can’t even go back to tend to his cocoa trees. After fleeing the attack, he wandered around the region, spending some time in a refugee camp in Nigeria. He hasn’t seen his wife and children for a long time.

Nearly every ADF soldier has a story like Abang’s. And the line separating these soldiers from refugees is very thin; their journeys are nearly the same.

Empty villages, angry refugees

More than 180,000 Cameroonians, mostly anglophones, are estimated to have been displaced during just eight months of conflict. This includes 160,000 inside the country and more than 21,000 refugees registered in camps in Nigeria, according to the UN. Real numbers may be a lot higher because many of them are hiding in the bush or have not yet been reached by humanitarian agencies. IRIN met a dozen would-be refugees in Cameroon and members of another group in Nigeria who claimed they were about 350-strong – none had met UN workers.

Among them is an old woman who sits in the shade of a palm tree – she’s one of those displaced by the conflict but still inside Cameroon. Her cane leans against the tree’s rough trunk and her legs are stretched out in front of her. She has given birth to 11 children, and raised them. But now they’re nearly all gone.

“They’ve killed my children, 10 children they’ve killed,” she says, in an ethereal voice. Her hands shake slowly, as if rustled by a gentle breeze. Pointing to a woman nearby cradling a baby, she adds: “She’s the only one who remains.”

The old woman goes on to explain how, a few months earlier, her children had been returning home to their village of Mavas from Akwaya. Army troops stopped them on the road and killed all of them, she says.

The rest of the family fled, moving to a small hut by their farm, a few hours’ walk from Mavas. The old woman’s surviving daughter explains that she had been pregnant at the time so they couldn’t make it the several days’ walk all the way to Nigeria. Now she seems more worried for her mother. “She’s been sick,” she says, “since her children died.”

Like many other villages in the anglophone regions, Mavas is now deserted. It used to boast a bustling market where farmers would bring their yams and you could eat some grilled fish and maybe drink a beer. Now, it’s completely empty. A couple of schoolgirls who’ve fled to Nigeria hurry to pack a few clothes they had left behind, before rushing away again.

ADF fighters act as guides through the empty village. Several of them used to live there and, like the old woman, had to flee.

One of the fighters walks into a large house with mud walls and a zinc roof. He opens a door with a broken lock and invites us inside. “This is my room,” he says, pointing with his rifle. A mosquito net hangs over a bed without a mattress. “They have carried it away,” he explains. “They’ve spoiled everything.”

He recalls the moment the army came in February. He had been playing with his sister’s children. Then the troops “just started shooting,” he says. He fled, and soon after joined the growing ranks of the ADF.

Ambazonia and independence

Even before the army drove them out of their homes, many of the ADF soldiers were angry. For decades, anglophones have felt marginalised by the centralised francophone government in a country that began as a federation. On 1 October 1961, the southern part of British Cameroons joined the francophone Federal Republic of Cameroon.

Today, Cameroon is officially bilingual, but French is often favoured. The two anglophone regions make up a sixth of the total population, according to the national statistics office. But competitive exams for the most prestigious public universities and colleges are given only in French, and those are the gateways to the sought-after public administration posts.

In the 1980s, anglophone protests against what many saw as a forced assimilation into the francophone educational system were violently quashed. In 1985, an anglophone lawyer, Fon Gorji Dinka, distributed a pamphlet calling for an independent anglophone republic, which he named “Ambazonia”. He was promptly arrested. Three years later, he escaped to Nigeria.

Fast-forward to September 2016, when street demonstrations began against the creeping use of French in the region’s schools and courtrooms.

The protests culminated in activists declaring the independence of Ambazonia in 2017 on the symbolic date of 1st October. Cameroonian security forces killed over 20 protesters and jailed more than 500 people, according to Amnesty International. Videos shared on social media showed police officers humiliating protesters by forcing them to roll in the mud.

The violence sparked the birth of several armed groups, including the Ambazonia Defense Forces. Their members kidnapped state officials, killed security forces, and sought to make the anglophone areas “ungovernable”. They have also closed schools, seen as symbols of the francophone Cameroon state.

Security forces have retaliated by killing dozens of civilians (an IRIN tally of local news reports and a separate estimate by the International Crisis Group think tank both indicate at least 100 is more likely since 2016), and by burning down several villages in the anglophone regions. Despite allegations of widespread human rights violations and recent reports of the army killing 32 self-identified separatists surrounded in one village, the Cameroonian government insists that all military operations have been in “strict compliance” with their rules of engagement.

Back at camp, listening to the ADF fighters, it is difficult sometimes to distinguish between systemic discrimination by the Cameroonian state and personal setbacks.

All have stories of unfair treatment, as do many civilian anglophones. One says he should have been hired for a government job but was passed over because he is an English speaker. Another says he and his classmates studied in English, and that because state exams are given only in French this prevented him and others from attending university.

Discrimination against the use of the English language ignited the armed rebellion, but IRIN’s interviews with the ADF fighters also point to long-held grievances over the lack of basic state services and economic stagnation in the anglophone regions.

Abang says he joined the ADF because the state took resources from his region, but he also accuses francophones of “deceiving” anglophones more generally. “I was working in Douala as an electrician,” he explains. “They only paid me 3,000 CFA ($5.40) when I had worked for more than 200,000 CFA ($360).”

The odds may be stacked against the fighters, but they seem undaunted, driven by their anger against the state.

“Until they kill me, I’ll do my best to fight, until I get my independence,” says Abang. “I’m not alone, we are many.”

Inside the separatist conflict

A fighter is rolling around on the ground, screaming, and muddying his bright-red basketball jersey. His colleagues take turns hitting him with a stick.

This punishment, 50 lashes, was ordered by *Omega, the field commander of this Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF) camp. The man had been “brutalising some people”, so “when the complaint got to me, I had to punish him severely,” Omega explains. “We don’t want the Ambaz’ name to be stained.”

Cameroon’s anglophone minority has felt marginalised for decades. During protests last October security forces killed and jailed demonstrators, spurring the birth of several separatist armed groups, including the ADF. The intensifying conflict has displaced more than 180,000 people, including tens of thousands who have fled into neighbouring Nigeria.

With their leaders in exile and a huge territory to control, the separatist leaders are under pressure to deliver military results while keeping their troops motivated and a spotless image. To achieve this, they resort to WhatsApp, social media, and magic.

Odeshi rituals

With a battle planned for the next day, Omega’s boss, *Atem, sorts out his equipment on a bed: a handgun, a couple dozen bullets, but also several necklaces and other amulets. His arsenal is as much spiritual as military. They call this magic “Odeshi”, and fighters believe it’s their only protection in their unequal fight against Cameroon’s US-trained army.

Atem is one of the most senior ADF commanders. He is well respected and known throughout the region as “Commando”, yet his crew still pokes at his portly belly when he takes his shirt off. The group’s hierarchy isn’t well established and Atem derives his authority less from his official rank than from his way with words: he knows when to listen, and when to tell someone off. Like many of the 1,500 other fighters the ADF claims to have, Atem was a farmer before the war.

Having gathered all his gear on the bed, he picks up his “battle shirt” – a sleeveless black top with amulets sewn onto the front – and puts it on. Around his neck, he hangs pendants of tightly stitched red leather, from which white feather quills stick out. Next, he puts bracelets around his biceps and on his wrists.

Each of these amulets, known collectively as Odeshi, has a specific task: a bracelet makes one invisible, a necklace jams the enemy’s gun, a goat’s tail waves off bullets etc. They each come with rules, such as fighting for a rightful cause, or avoiding specific foods.

Atem’s skin carries thin scars born of previous rituals. The previous day, he paid a traditional healer, a “baba”, to perform such a ceremony to protect him from bullets. The baba sacrificed a chicken and cut Atem’s skin with a razor before rubbing a grey paste into the wounds.

Once he is satisfied he has everything he needs, Atem carefully packs his equipment into the small bag he will take with him to battle.

The night before battle

After a long trek to the site of the battle, night comes. Atem lies on a filthy mattress next to another commander – they picked the best spot in the house. The other separatist fighters are stretched out on the bare ground, resting before the attack.

At dawn, about 40 fighters plan to take on heavily armed government soldiers, but if the army is tipped off then the ADF might be attacked first – the government forces would probably kill all of them, as they did a few days earlier with about 30 separatists from another group, spilling so much blood it gathered in shiny pools on the floor.

In the yard, a battalion of goats trots past wildly, perhaps aroused by the bright grey light of the full moon. Doors bang in the wind.

Near the entrance, two young boys are on sentinel duty, sharing an old rifle between them. They ward off sleep by smoking cigarettes and quietly exchanging stories. Once in a while, one of them gently pokes the other awake. The commander has warned that if he catches anyone sleeping on their watch, he’ll shoot them in the leg.

The group’s only other defence to ward off a surprise attack is in a dark corner of the house: a small shrine with mysterious vials, bits of cloth, and amulets dusted with white talcum powder. The air smells of the perfume used to activate their magical powers.

When the sun finally rises, the fighters are loitering around the yard, waiting. A large bag of bullets has gone missing. The person entrusted to bring it apparently decided it would be more profitable to pocket the ammunition than fire it, and disappeared. This mission is cancelled. On this occasion, the Odeshi will not be called upon.

Remote control

All of the fighters use Odeshi, but it does not vanquish all fears.

“Some fighters use drugs that motivate them to go to the field,” says Omega, who allows his men to take tramadol, a powerful opioid painkiller, although he doesn’t use it himself. “You don’t have fears in you again,” he says.

The trouble, Omega explains, is when combatants keep on taking the drugs when they’re back at the camp. It’s not very common, but then it’s harder to keep them disciplined.

Some armed men harass civilians for food, while claiming to be part of the ADF, Omega says. Then, he explains, he sends his men to keep them in check: “Any group that is out for terrorism, we are going to finish the group so that the country should be in peace, rather than in pieces.”

The separatists have been appealing to the international community to force the government to give them independence, so keeping a clean image is crucial.

The ADF has a Code of Conduct stating that “no fighter of the ADF shall engage in rape, extortion, theft of property, torture, or killing of innocent civilians.” And Cho Ayaba, the leader of the political wing of the ADF, says he issued orders banning the use of drugs.

But he is very far away, in Europe.

In 1998, Ayaba fled Cameroon aboard a timber ship, after narrowly escaping arrest for his political activism.

Like him, most of the political leaders of the half dozen or so anglophone separatist armed groups live abroad – a necessary measure in a country like Cameroon. In early 2018, 47 anglophone leaders were arrested in Nigeria and deported to a jail in Cameroon. They were held incommunicado for six months and only recently allowed see their lawyers.

So WhatsApp is the only way Omega, Atem and other commanders can get orders from their leaders. They know every patch of dirt where the phone network can be reached by clambering on big rocks, hiking to the top of hills, or sheltering beneath a tree’s branches. Much of the time, though, they are off-grid.

Recently, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have accused the separatists of violently enforcing the boycott of government schools by destroying over 40 schools and assaulting teachers who refused to comply. They’ve also been accused of kidnapping civilians suspected of working with the government.

The ADF has denied abuses against schools and civilians, apart from “arrests” of government allies. Ayaba says he takes “responsibility for whatever the ADF does”, but insists he is not “micromanaging” the actions of the group. “I provide political leadership, an inspiration, the roadmap.”

Yet, he warns that the ADF and other separatist groups may not be able to stick to their rules of engagement forever.

“If you let the conflict fester for too long and the regime continues with this level of brutality, it will be completely impossible to control everybody. And some of these abuses might just increase,” he said, referring to some attacks against francophones.

Cameroon’s presidential elections will be held on 7 October, and with them comes the threat of a new spike in violence. The ADF spokesman warned there “shall be no elections of the President of Cameroon in Ambazonia territory”, and one of their prominent “generals” has already announced that he’ll kill anyone who gets near a voting station.

(*The names of the separatist fighters have been changed for their protection)

About the author:

* Emmanuel Freudenthal, Freelance journalist, and regular IRIN contributor

Source:

This article was published by IRIN in a two part series, which can be found here and here.