Civil Society And Web 2.0 Technology: Social Media In Bahrain – Analysis

By Magdalena Maria Karolak

The revival of academic interest in the concept of civil society that begun in the years 1970s and 1980s was linked to the democratic transformation experienced in the world (Dziubka, 1998). The importance of citizens in the success of Third Wave of Democratization (Huntington, 1991) cannot be overlooked.

Scholarly attention was focused on the interrelations between a healthy and prospering democracy and the existence of civil society (Dahrendorf, 1996). However the overview of the Arab world, where authoritarian regimes prevail, shows that relying on civil society alone may not be enough. It is important to note that civil society does not constitute a sufficient condition to generate democratic change by itself (Yom, 2005). but far from being pessimistic, our research shows that civil society, as it grows in partially controlled regimes, can play an important role in the development of democratic values. The spread of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) provides a powerful tool that can strengthen the role of civil society as “a promoter of democratic values, [providing] model of active citizenship and [tempering] the power of the state.” (Kuchukeeva & O ‘Loughlin 2003, pp. 557–58 ).

Anheier defined civil society as “the sphere of institutions, organisations and individuals located among the family, the state and the market, in which people associate voluntarily to advance common interests” (2004, p.11). In our research we are going to focus on the role of blogging in the creation of civil society, which falls in Anheier’s sphere of individuals. This category includes people’s activities in civil society such as “membership, volunteering, organizing events, or supporting specific causes; people’s values, attitudes, preferences and expectations; and people’s skills and in terms of governance, management and leadership” (2004, p. 11). We also find useful Habermas’s concept of civil society as a public sphere. Public sphere is defined as “a network of communicating information and points of view (i.e. opinions expressing affirmative or negative attitudes)” (1996, p. 360), which is closely linked with blogging activity. Gibson emphasized that in societies that lack civil and democratic values strong ties to family and the clan tend to be a prevalent form of association “inhibiting interactions with those outside the network” (2001, p. 188). The creation of “weak ties” in the form of social networks is thus especially important in order to make the spread of new ideas possible. We are going to analyze how the Internet contributes to the formation and growth of civil society in Bahrain.

Internet as a tool

Habermas believed that new technologies, especially the spread of commercial mass media, were detrimental to the public sphere. Many scholars saw however that new forms of communication created an unprecedented opportunity for the growth of civil society. Castells (2007) goes as far as to say that the Internet can constitute an alternative to classic forms of civic engagement. The Internet is regarded as the new space, the “alternative public sphere where, for instance, politics and the people can meet again and finally start communicating” (Ester & Vinken, 2003, p.669).

The Internet is one of the most important developments in communication technology and the advantages that it offers to citizens are innumerable. The Internet breaks the monopoly of communication that was previously confined to traditional elites, such as the government, church or political parties. It empowers each individual to become a political broadcaster and voice his/her opinions on an equal footing with any other user. It fosters pluralism because in cyberspace there are no set answers in the form of dominant ideologies. Communication is characterized by informality, which may in turn encourage further freedom of expression. Moreover the Internet creates an area that is difficult for the government or other entities to control – an important advantage in states where media are centrally controlled.

Another strength of the Internet lies in its accessibility. The users can access the network in their own time and be in instant contact with whoever is connected. The Internet can potentially connect the sender to an unlimited number of users. It enables the creation of new networks such as chat rooms, web forums and mailing lists. It helps not only challenge the official ideologies but also furthers dialogue and shapes opinions. The Development of democratic values can occur through “processes of diffusion and through practice at democratic discussion.” (Gibson, 2002, p. 189)

Given these advantages the Internet is a powerful tool that can change the face of societies in the Middle East. A number of scholars have emphasized differences between the development of civil society in Western civilization and in the Middle East. The main driving force for citizens in Western society lies in the individual initiative, and not in a group thinking, as well as being an active citizen influencing the policies of the state. In the Arab world on the other hand, the history of state development put stress on states and on inspired leaders. “The status of the regime is considered more important than providing individual rights and freedoms, and also more important than enhancing the contributions and private initiatives of individuals in political life.” (Samad, 2007) Given the historical conditions that have been determining the development of Arab civil society, ICT could mark a turning point in the trend by empowering common citizens. It can potentially have an enormous impact on young generations. However technology is not sufficient in itself to provide for social activism. Political reforms undertaken in recent years had also an impact on development of civil society.

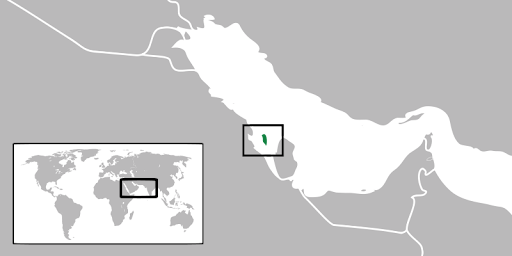

Bahrain as a case study

Political activism is not new to Bahrain‘s society. Political mobilization in the 20th century was centered primarily on the issue of independence, which was granted in 1971. After gaining independence, Emir Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa promulgated the first constitution in Bahrain anf the first parliamentary elections took place in 1973. Two years after its establishment, the Bahraini parliament was dissolved and it remained in abeyance for almost 30 years. Lack of consenus on foreign and internal policies led to a split between parliamentarians and the emir. The beginning of the 21st century marked a change in Bahraini politics with the ascension to the throne of Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. His predecessor, Emir Isa Bin Salman Bin Hamad Al Khalifa (1961-1999) ruled the country with a strong fist. In 2000 Sheikh Hamad initiated a plan to establish the National Action Charter. It was submitted afterwards for approval in a national referendum and was overwhelmingly accepted by society with 98.4 percent of Bahrainis voting in favor. On December 16, 2002, Bahrain became a kingdom and a new constitution was adopted the same year.

The controlled liberalization of the country initiated by Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa in 2002 was long-awaited by society.

Bahrain became a monarchy and civil rights were restored. The Bahraini constitution guarantees freedom of speech provided “that the fundamental beliefs of Islamic doctrine are not infringed, the unity of the people is not prejudiced, and discord or sectarianism is not aroused” (Article 23). A bicameral parliament was re-established with the Council of Representatives, the lower house, elected in universal suffrage. Parliamentary elections were held in 2002 and 2006. In 2002 for the first time, municipal elections were held. These events had an important impact on society. They offered an environment where citizens could participate and make their choices. Although there were well-established limits to participation, the elections and parliamentary oversight of government opened doors for political discussion.

The political changes were accompanied by the liberalization and privatization of the telecommunications industry in 2004. Bahrain saw strong growth in the ICT and is at the top in the GCC region in terms of phone and Internet connectivity (Bahrain Economic Development Board, 2009). Internet connectivity was estimated at 649,300 Internet users as of September 2010, which was roughly equivalent to 88 percent of Bahrain’s inhabitants (Internet World Stats).

Our study is composed of two parts. To begin with, throughout 2010 we have analyzed the existing Bahraini blogs that were at the center of the exchange of political ideas. However at the beginning of 2011 the focus shifted to Facebook. Following the example of other Arab countries, Bahraini activists organized themselves on Facebook to promote a national “Day of Rage”. Thus the second part of the study is entirely devoted to the assessment of Facebook sites and their role in shaping recent events in Bahrain.

Overview of Bahraini blogs

Increased Internet connectivity led to the formation of forums, thematic websites and chat rooms, but our main interest lies in blogs. Blogs (web logs) are personal websites where entries are written in chronological order and commonly displayed in reverse chronological order (Rettberg, 2008). Blogs vary widely in their themes but they all share the characteristic of “frequency, brevity and personality” (Rettberg, p. 21). Blogs usually develop over a long span of time and offer an insight into subjects important to the author throughout the life of the blog. Discussions with followers or fellow bloggers are centered on these particular issues. We can observe an exchange of opinions and discussions leading sometimes to the formation of a common standpoint. Bloggers who are individually in charge of their own blogs enjoy greater creativity and freedom of expression.

Our research aimed at finding blogs created by Bahraini citizens or residents living in Bahrain. The statistics reveal a total number of roughly 150 blogsi in 2010. This number is extremely low even taking into account Bahrain’s population of 1.04 million, at less than 0.02 percent. In comparison, an estimated 68 percent of Singapore’s population are bloggers, one of the highest blogger activity rates in the world. It has been observed that in the Arab world “blogging remains the activity of a tiny elite, as only a small minority of the already microscopic fraction of Arabs who regularly use the Internet actually write or read blogs” (Lynch, 2007).

The Bahraini community of bloggers, although small, is well connected through regular meetings of bloggers, as well as through websites such as the Bahrain blog aggregator, which provides a compilation of new blog entries.

Topics

Blogs have been categorized according to subjects present in the content. In our study, the term political blog denotes a blog whose author devotes a large part of comments to politics. However other subjects may be present. The non-political blog either does not have any comments related to politics or such comments form an insignificant part of the content. Of the 150 blogs examined, 40 (27 percent) would qualify as political and the remaining 110 as non-political. Ninety-eight (65 percent) of the 150 bloggers write mainly in English, 42 of them mainly in English and 10 of them in both languages roughly in equal amounts. One hundred and 28 (85 percent) are of Bahraini nationality and the remaining 22 are non-Bahraini residents of the island.

Overview of political blogs

The main focus of our study lies in the subjects related to politics. Blogs that were categorized in this section are not completely devoted to political events, but a significant part of the entries relate to politics. Among the 150 blogs found, 40 fall in the category of political blogs. Great disparities in the size of content and in popularity exist between particular blogs. One blog stands out as the most important in terms of longevity, content and number of visitors. Mahmood’s Den, the blog of Mahmood al-Yousif located at http://mahmood.tv, has existed since 2001ii and according to the statistics of its author receives “an average of 4 million hits, about 1.2 million page views and around 175,000 unique sessions a month” (Khonji, 2006) from readers all over the world. The blog has more than 3,000 posts in its archives and offers a combination of text, pictures and videos. As a comparison, Silly Bahraini Girl blog, second in terms of content size, generated roughly 700 posts from 2004 to April 2010. The influence of Mahmood’s Den on other bloggers earned al-Yousif the nickname Godfather of Bahrain’s bloggers. Mahmood’s Den provides useful tips on how to start one’s own blog and promotes the Bloggers’ Code of Ethics introduced by CyberJournalism.com.

Blogs as school of democracy: political subjects and recommendations

Although each blog has a specific character, authors share many observations in the area of political developments. The main subjects that appear simultaneously in most blogs include assessment of members of parliament, criticism of policies and protests against Internet censorship. For Gellner (1994) civil society entails political accountability. Consequently agents of civil society can provide an effective check on politicians. This role is especially important in societies where general elections are a novelty.

The second parliamentary elections in Bahrain in 2002 generated much interest with a turnout of 53.2 percent. However, in the third elections in 2006 the expectations of voters rose as the political system became more mature, and the major opposition party Al Wefaq took part in elections after a boycott in 2002. Voter turnout in 2006 consequently reached 72 percent. Sunni and Shi’a political associations dominated the parliament. Bloggers followed developments in the political scene with enthusiasm, but were critical of the abilities and general strategy of the political associations. According to bloggers, MPs lacked the “ability to compromise and […] knowledge of the political game” (AlMannai, 2008) and were “amateurs […] still learning what it means to be in parliament, what it means to have rights and responsibilities” (Merlin, 2007). Fellow bloggers pointed out in many instances that MPs lacked the appropriate background to carry out their tasks: “Figures issued to MPs by the Public Commission for the Protection of Marine Resources, Environment and Wildlife about the quality of air make no sense whatsoever. However, not a single MP stood up at the meeting to question what they meant” (AlHussaini, 2005).

Bloggers criticized the overwhelming focus of MPs on moral issues rather than on providing solutions to the country’s real problems. The years 2008 and 2009 witnessed a number of proposals aimed at preserving the religious identity of the country. These included a complete ban on pork, alcohol in public places, entertainment in hotels, concerts and witchcraft.

Parliamentarians were criticized for ignorance, restraining freedom and possibly causing damage to Bahrain’s economy. Debates over the ban on alcohol were especially strong. MPs supported their decision by claiming that the consumption of alcohol leads to increased crime. However, as observed one of the bloggers, MPs failed to provide any statistics linking the two. Municipal councillors on the other hand proposed a clampdown on mannequins for lingerie in display windows, fitting new buildings with one-way windows to prevent passer-bys looking in from outside and relocating bachelors away from residential areas. Bloggers were outraged at the lack of genuine progress: “All that time wasted discussing legitimate entertainment activities, which have been approved by the state, could have really been utilised to carefully scrutinise an issue as serious as the quality of the air we are forced to breathe” (AlHussaini, 2005). They also questioned the personal integrity of some of the Islamist MPs (Lulu, 2007). Other bloggers reflected further on the overall lack of strong leadership in the Arab world on the international scene.

The incompetence of parliamentarians made bloggers conclude that the core problem lies within voters themselves, who elected the MPs and are responsible for the choices made. Blogger Khonji observed that voters choose candidates based on religion and ethnicity and do not assess the actual competencies of the candidate (2006b). Some bloggers reflected further on the state of Bahraini society and were critical of animosities and the lack of political education. Demonstrations under the name of democracy took place in 2007 and 2008, leading occasionally to vandalism. Tariq Khonji commented in his blog: “Isn’t it funny to see people calling for democracy while destroying public and private property – and actually demanding restrictions on personal freedom?”

Opposition political associations did try to challenge the current political system, asking for further democratic changes. But the very same associations called for the strict implementation of Islam, including restrictions on the role of women in society.

Another issue that concerned bloggers was Internet censorship. Regulations in 2002 imposed censorship on publications, including websites, which were critical of religion and of government authority. A number of websites that did not include any prohibited content were blocked randomly. Bloggers pointed out the inconsistencies that led to the ban on the Google Translate page or to random disruptions of access to some Facebook accounts. This policy made Bahrain slip in international rankings of press freedom – a fact that bloggers noted did not appear in the local news (Horton, 2009).

Women bloggers emphasized issues of specific importance to women. Bitter disputes in parliament were waged over the proposed family law (Personal Status Law). The new law would codify divorce rights, alimony and child custody issues, replacing the traditional interpretation of Sharia judges in these matters. Al Wefaq categorically opposed lay interference in issues traditionally reserved for Sharia scholars. A number of posts criticized the role of Islamist political associations in pressing for restrictions on women’s participation in society.

Achievements and future considerations

After this general overview of blogging activity it is important to analyze whether blogging has had any effect on Bahrain’s society and political system.

In order to curb growing criticism, Internet filtering was introduced in 2002. It led to the blockage of several blogs, among other websites. Bloggers then employed the tactic of moving their blogs to other URLs, thus rendering the blockage useless (Bell, 2005).

The Bahraini Ministry of Information then required the formal registration of “all blogs hosted in the country or written by its citizens” in 2005, stating as a reason the need to protect author’s “rights of authorship” (Riley, 2005). The lack of response on the part of the bloggers led the ministry to abandon the registration requirement. Moreover bloggers started an initiative to monitor the number of blocked websites and introduced an online petition to stop the censorship. Critical remarks caused a wave of trials of bloggers and journalists in Bahrain and in other GCC countries, including blogger Ali Abdulemam. A campaign of solidarity on the part of fellow bloggers led to his release (Schleusener, 2007).

Apart from blogging, Bahrain has witnessed a growth in the number of civil organizations. Non-governmental associations such as the Bahrain Businesswomen’s Society2, Bahrain Women’s Association for Human Development, Bahrain Women’s Association or Women’s Petition Committee promote gender equality but also, in the three latter cases, protection from unjust treatment and abuse. Women’s associations have become more and more vocal on the political scene, demanding the reform of women’s status in society. Human rights associations, including the Migrant Workers Protection Society, also operate successfully in Bahrain.

Although blogging activity is limited in Bahrain, the community has been able to continue to participate in the creation of civil society in Bahrain. It provides a check on elected politicians and exercises pressure to safeguard freedom of speech. Added to the growing numbers of NGOs, Bahrain’s population can enjoy a beneficial impact of what Putnam describes as the inculcation “of skills of cooperation as well as a sense of shared responsibility for collective endeavors. Moreover, when individuals belong to ‘cross-cutting’ groups with diverse goals and members, their attitudes will tend to moderate as a result of group interaction and cross-pressures.” (p. 90).

Nonetheless, it is important to note the limits of civil society in Bahrain, which have been visible in the aftermath of the “Day of Rage”.

The Facebook Revolution and the sectarian divide

The series of recent uprisings in the Middle East has been often called Facebook revolutions because of the role of the social network in gathering supporters, organizing the movement as well as coordinating protests. This idea was readily adopted by Bahraini opposition to the government. Anti-government sentiment had been fermenting in Bahrain for the past three decades, leading occasionally to violent upheavals. The protests intensified in the 2000s. In 2005 and in 2008 Bahrain was shaken by Shi’a demonstrations based on economic and political demands, occasionally leading to riots in public places including shopping malls, restaurants and concerts. The opposition planned nationwide protests during the Formula 1 race in May 2009, an event that attracts international visitors from all over the world. However these plans were unsuccessful because of containment by the government. The successes of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions provided an opportunity to bring international sympathy and attention on Bahrain. Thus Bahraini activists organized themselves on Facebook, promoting the idea of a national “Day of Rage”.

They called on all their followers to take to the streets and organize an Egyptian-style occupation of Bahrain’s largest square.

The situation in Bahrain is complex, however, due to the social composition of the Bahraini population. Ninety-eight percent of native Bahrainis are Muslim. Jews and Christians make up the remaining two percent. Shi’a Muslims are more numerous and account for more than 60 percent of Muslims in the kingdom (Nasr, 2006). Arab Shi’as say they are the indigenous inhabitants of the land. Ruled by the Sunni Al Khalifa dynasty since the beginning of the 19th century, they often claim to be victimized as a whole group. However they do not form a homogeneous population but are divided along ethnic lines into the Arab Shi’a (the Baharna), the first occupants of the islands, and Shi’as who migrated afterwards from Iran (the Ajam). Tensions between the two groups are not uncommon (Rabi, 2008). The “Day of Rage” protests and the following events divided Bahraini society even further. Most importantly, they exacerbated the sectarian partition of society. Religious affiliation in Bahrain was a social cleavage that already existed. In the wake of the 2005 protests a Bahraini blogger commented on his site: “Al Wefaq is really desperate to participate in the political arena. Unfortunately, the Shia Islamist group seems to be the only opposition group that has the desire to make a difference. Yesterday’s protest was a one party, one sect demonstration. Again I ask, where is everyone else?” Other segments of society did not take part because they did not share the political goals of the Shi’a. On the contrary, they watched the events with growing resentment and even outrage, and some believed Iranian influence was at work to divide Bahraini society (Santana, 2009). This perception was reinforced by the “Day of Rage”. Moreover, due to the unfolding events, all citizens were gradually forced to take a stand by supporting or opposing the movement. The gap between the two camps is wider than ever before.

The revolutionary and the anti-revolutionary

The division of Bahraini society is easily visible on Facebook. Competing sites bring together the protesters and their opponents. The Arabic site “Revolution 14 February in Bahrain” gathers as many as 68,000 followers. Its bilingual counterpart “14th February 2011 Revolution Day in Bahrain” is followed by almost 8,000 users. On the other hand, a variety of sites unite the anti-protest movement, including “We Are Bahrain” (22,000 followers) and “We are with you Bahrain! United against the protests!” (more than 12,000 followers). Other sites are devoted to a specific cause, such as supporting the police or the military. Because of the fluidity of Facebook at the moment, we reckon it impossible to enumerate all the sites that exist within this social network.

The uses of social networks are innumerable for both protesters and their opponents, beyond the purpose of coordinating supporters for demonstrations. Facebook provides followers with real-time updates: pictures and videos taken during events are uploaded within minutes and shared with the community of followers. Facebook also carries witness accounts of events, often challenging existing channels of information. Moreover, it serves to coordinate help such as donations. Most importantly, it has an important psychological effect. Network users gain in solidarity and mutual support. Commonly emphasized feelings are sacrifice for the country and martyrdom.

The analysis of four Facebook sites mentioned above reveals dividing lines over recent events. Although none of the sites explicitly states a particular religious or ethnic affiliation in its profile, the comments posted and the discussion that ensue show a division into specific groups. The questions raised relate to the issue of loyalty, media portrayal of the events and truth, racism and peacefulness. We will briefly present each of these points by analyzing the content of the sites.

Both protesters and their opponents construct a strong sense of belonging surrounding their cause. It is highlighted by the use of pronouns such as “we”, “our” as opposed to “they” and “their”. Both groups present themselves as victims and those killed on each side are called “martyrs”. The Other is often described using labels. Those supporting the government are often referred to as “slaves” and “cowards”. On the other hand, the opposition is branded as “terrorists” who place their loyalties with “Iran” and “Hezbollah”. Protesters are thus accused of being “traitors” who secretly “gather weapons” to carry out the instructions of foreign powers. Moreover, each of the groups presents itself as being under “attack”, while the Other constitutes a “threat”. Consequently the arrival of military forces from neighboring countries was seen as either an “occupation by foreign armies” or a sign of “unity” on the part of Arab governments.

Another point of discontent is the portrayal of events by the activists themselves and by the media. Both groups accuse the other of providing a one-sided version of the story, sometimes falsifying the reality. The protesters accuse the security forces of brutality after several protesters were killed or injured. They also underline aggression towards medical personnel and unarmed civilians including women. Uploaded videos and pictures serve as testimony to both sides of the conflict. But the pro-government sites present a completely different image. The protesters are shown provoking the security forces, carrying weapons and themselves involved in acts of brutality against the police and expatriates from the Indian subcontinent. Since these versions differ considerably, each group accuses the other of editing the footage to serve their purposes or even fabricating the videos. Both groups denounce national and/or international media. The protesters claim the national media do not do them justice and “is lying”. Their opponents criticize coverage of the events by some international media as completely biased.

Consequently, the issue of peacefulness is raised. Both sides present themselves as peace- loving people who seek protection of their just rights. The anti-government side seeks “freedom”, while the pro-government side wants “protection” and “peace”. In addition, Facebook comments take a racial twist. Since the security forces involved include a large number of employees from the Indian subcontinent and from other Arab countries, the protesters call them “mercenaries” who “would do anything to get a passport”. The pro- government side presents them as “brave” people who perform their jobs while risking their lives. This is shown in contrast to the protesters themselves, who are ridiculed as having a “picnic” and engaging in immoral behavior on Pearl roundabout.

In certain instances Facebook sites underline that they make no generalizations about specific religious or ethnic groups since some of their members may be misjudged this way, but the emotional factor plays a further role in splitting public opinion. Pictures and video clips taken at the funerals of “martyrs”, often portraying grieving families, cause uneasy sensations among viewers and may easily stir up feelings of revenge.

All in all, the Facebook sites analyzed are proof of a deep polarization in Bahraini society. There is no debate on how to solve the situation. Quite on the contrary, many of the users engage in a “war of words”. Moderate comments are usually ignored.

Conclusion

Bahraini civil society is still in the process of formation. Although a growing community of bloggers initially had a positive effect on civil activism, recent events have led to a drastic increase in antagonism between different segments of society and to the radicalization of opinions. The inability to reach consensus leads to escalation and conflict. Kapuscinski described the effects of lack of civil society after the fall of the USSR in Central Asia. The sudden end of a totalitarian state prompted “hundreds, thousands, of various interests [to] emphatically demand the rights long denied to them. In a democratic state there is of course also a multitude of various interests, but the contradictions and conflicts between them are resolved or softened by experienced, well- tried public institutions. […] In the place of the still-nonexistent institutions of arbitration, the simplest path emerges, the path of force” (2007, p.127). The problem of further division is a growing challenge to Bahraini society. Private initiatives to stop the divide exist, such as an Internet action launched under the slogan “Not Shi’i, Not Sunni, Just Bahraini“. However they have so far had a limited impact on society.

Author:

Magdalena Maria Karolak

New York Institute of Technology College of Arts and Science, Adliya, Kingdom of Bahrain [email protected]

Source:

This article was published by Arab Media & Society, and was peer-reviewed. The article may be accessed here (PDF).

References

AlMannai, A. (2008, March 11). Parliament – Helmets and Pads Not Included. Message posted at: http://almannai.blogspot.com/2008/03/parliament-helmets-and-pads-not.html.

AlHussaini, A. (2005, May 26). MPs once again fooled by a few figures… Message posted at: http://sillynotes.blogspirit.com.

Anheier, H. K. (2004). Civil Society: Measurement, Evaluation, Policy. London: Earthscan.

Bahrain Economic Development Board (BEDB). (2009.). Arab advisors group reveals Bahrain’s communications connectivity leading the region. Retrieved January 6, 2010, from www.bahrainedb.com

Bell, G. (2005, November 2). TheArabregion’sboldnewbloggers.Onlinejournalism.Retrievedfrom: http://journalism.cf.ac.uk/2007/online/index.php?id=parse-195-0-0-251&article=510&author=Gillian+Bell

Blogging is booming in Singapore. (2010). Retrieved from: http://advertising.microsoft.com/asia/Home/Article.aspx?pageid=&Adv_ArticleID=4964

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, Power and Counter-power in the Network Society. International Journal of Communication. 1, 238-266.

Dahrendorf, R. (1996). Wolność a więzi społeczne. Uwagi o pewnej argumentacji. In Społeczeństwo liberalne. Rozmowy w Castel Gandolfo (pp. 9-18). Kraków: Znak.

Dziubka, K. (1998). Społeczeństwo obywatelskie: wybrane aspekty, ewolucja pojęcia. In Jabłoński, A. W. & Sobkowiak L. (Eds.), Studia z teorii polityki tom II (pp. 31-52). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.

Ester, P. & Vinken, H. (2003). Debating Civil Society: On the Fear for Civic Decline and Hope for the Internet Alternative. International Sociology, 18, 4.

Gellner, E. (1994). Conditions of Liberty: Civil Society and Its Rivals. New York, NY: Penguin Books,

Gibson, J. L. (2002). Social Networks, Civil Society, and the Prospects for Consolidating Russia’s Democratic Transition. In

Ethridge, M. E. (Ed.), The Political Research Experience: readings and Analysis. New York: M. E. Sharp Inc.

Habermas, Jurgen (1996) Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Horton, L. (2009, April 22). The Censorship Saga Continues… Message posted at http://letsblamesociety.blogspot.com/2009/04/censorship-saga-continues.html.

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Internet World Stats. (2009). Retrieved from: http://www.internetworldstats.com/middle.htm

Kapuscinski, R. (2007). Imperium. London: Granta Books. Khonji, T. (2006, February 6). 60 Seconds Interview. Gulf Daily News.

Khonji, T. (2006b, November 20). Prevent Idiots from Getting Elected…! Message posted at: http://www.tariqkhonji.com/main/elections.htm.

Kuchukeeva A., & O’Loughlin J. (2003). Civic engagement and democratic consolidation in Kyrgyzstan. Eurasian Geography and Economics 44(8), 557-587.

Lunch, M. (2007). Blogging the new Arab public. Arab Media & Society, Vol. 1. Retrieved from: http://www.arabmediasociety.com/?article=10

Lulu, (2007 April 5). Islamist hypocrite. Message posted at: http://lulubahrain.blogspot.com/2007/04/islamist-hypocrite.html

Merlin, (2007, August 5). Message posted at: http://mahmood.tv/2007/08/05/shia-triple- play/#comments

Nasr, V. (2006). The Shia revival: How conflicts within Islam will shape the future. New York: W. W. Norton.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rabi, U. (2008). The Shi’i Crescent: Myth and Reality. Retrieved 2010, 12 January, from www.strategicdialoguecenter.org.

Rettberg Walker, J. (2008). Blogging. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Riley, D. (2005, April 29). Bahrain to force bloggers to register with Government. The Blog Herald. Retrieved from: http://www.blogherald.com/2005/04/29/bahrain-to-force- bloggers-to-register-with-government/

Samad, A. Z. (2007). Civil Society in the Arab Region: Its Necessary Role and the Obstacles to Fulfillment. International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law, 9 (2).

Sater, J. M. (2007). Civil Society and Political Change in Morocco. New York: Routledge.

Schleusener L., (2007). From Blog to street: The Bahraini public sphere in transition. Arab Media & Society, Vol. 1. Retrieved from: http://www.arabmediasociety.com/index.php?article=15&p=0

Yom, S. L. (2005). Civil Society and Democratization in the Arab World. Middle East Review of International Affairs. Article 2, Vol. 9, No. 4.

i The actual numbers might vary since some blogs were blocked at the moment of writing. ii The archives of the blog go back to 2003.