India And Its South Asian Neighbors: Perceptions Of Threats And Realities – Analysis

Shift in India’s Approach Towards its Neighbors was Short-lived

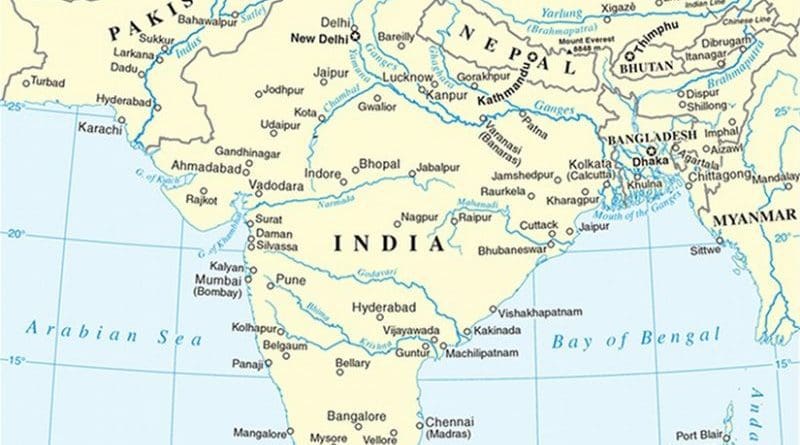

The most formidable obstacle to the South Asian regional integration process has been pre-occupation of the states with a state-centric approach to security. In the initial years since South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) came into existence in 1985, India hesitated to get actively involved in the regional forum as it believed the group was intended to be a platform for smaller powers to gang up against India given the initial move for establishing the South Asian regional grouping was made in January 1980 in the in the context of the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan and the US and Pakistani resolve to resist the intervention.

The Gujral doctrine, propounded by the former Minster of External Affairs I.K. Gujral in 1996 who later became Indian Prime Minister, was a response to address an atmosphere of distrust that characterized India’s relationship with its neighbors for long starting from India’s unequal treaties with Nepal and Bhutan keeping the protectorate arrangements of British India intact under Nehru’s leadership to the evolution of Indira doctrine designed to keep the external powers out of the South Asian region and compel the neighbors to seek India’s assistance to resolve their problems onto Rajiv Gandhi’s commitment to follow Indira doctrine to its conclusion by intervening in Sri Lankan civil war.

The doctrine marked a departure from India’s earlier obsession with keeping the region within its orbit of influence to an inclination for non-interference and non-reciprocity. For instance, India stopped intervening in neighboring states’ foreign policy decisions that was previously considered crucial to India’s security. For instance, India did not contest Sri Lanka’s arms purchase from Pakistan. The principle of non-reciprocity which demanded unilateral positive gesture from India to maintain neighborly relations irrespective of the capacity of other small states to reciprocate allowed India to gradually convert existing treaties with neighbours into free-trade agreements.

However, euphoria surrounding the Gujral doctrine subsided quickly, as the Chinese footprint in the region became more pronounced and likelihood of China-Pakistan axis in the region became palpable to India’s foreign policy makers. New Delhi began to view regional developments from a military security driven perspective instead of pushing for regional integration.

The perception and narrative of Chinese threat has been built around many developments such as India’s defeat in the 1962 border war which was considered a breach of trust and violation of the spirit of ‘Panchasheela Agreement’ signed between the two countries, continuous Chinese supply of arms and nuclear technology to Pakistan irrespective of India’s concerns, Beijing’s flexing of muscle in its neighborhood, occupation of Tibet and expansionist territorial claims by portraying Arunachal Pradesh-an Indian territory as part of China and its palpable intrigue in its unwillingness to disrupt its ally Rawalpindi’s alleged connection with religious radical groups for instance, New Delhi’s move to question Islamabad and seek UN Security Council sanctions against Hizbul Mujahideen Chief Syed Salahuddin, the mastermind of the Mumbai attacks, was blocked by Beijing.

India’s Military Strategy and the Region

The lesson that India learnt since 1962 border war was its lack of conventional military ability to take on China. India has ever since more focused on developing its military capacity by modernizing and investing larger portion of its budget towards defence preparedness.

As per data on arms transfers released by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), arms imports by India increased by 24% between 2008-12 and 2013-17 periods. More intriguingly, the data project India as the world’s largest arms importer accounting for 12% of the total global imports for the period 2013-17. It is very much clear that India’s defence preparedness is directed more towards China than Pakistan over which India already enjoys military superiority.

However, what is glossed over in this strive for military build-up is that India is continuously bleeding as a result of growing instances of cross-border terrorism and proxy-wars which cannot be contained let alone wiped out by its increasing conventional military capacity. Outcomes of a 74-day long military stand-off between India and China in Doklam located on the strategic tri-junction of Bhutan, China and India went in favor of India as both China and India not only agreed to return to their previous position, Beijing stopped its road construction activities in the area. While this action pointed to India’s military resolve to insulate the South Asian region from Chinese territorial incursion, this has also fed into the narrative that India needs to continue to strengthen and modernize itself militarily not only to avoid a humiliating defeat of 1962, it would also be able to deter China from making military inroads into the South Asian region.

India’s Perception of Looming Chinese Threat in the South Asian Region

India perceived a greater threat from Chinese foray into the South Asian region than threats emanating from Pakistan in the form of terrorism and proxy wars. Many Indian leaders and experts expressed their concerns regarding Chinese inroads into the region and a parliamentary committee report on external affairs noted “China is making serious headway in infrastructure projects in our neighborhood…..the Indian government is committed to advancing its development partnership with Bhutan and Nepal, as per their priorities”.

Experts on Security Affairs furnished a geopolitical theory on Chinese foray into the region known as ‘String of Pearls’ strategy in academic literature. While Beijing uses catchphrases like ‘One Belt One Road’, Silk Road and Maritime Silk Road project to emphasize its economic thrust and regional necessity, India perceives a threat of ‘encirclement’ in the Chinese move. The Chinese project has already taken off in the form of construction of roads, railways and air ports in landlocked Nepal to creation of ports, bridges and airport facilities in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and the Maldives.

What makes India’s concerns look more genuine is roads, railways, bridges and ports can be used for dual purposes – civil and military. There may be ulterior military objectives underlying Chinese mega connectivity project which cannot be denied only on the basis of official declarations from Beijing. These threats are getting more pronounced when India, under Modi’s leadership and in line with his ‘neighborhood first’ policy, played a leading role in the deliberations of the 18th SAARC Summit held at Kathmandu on November 26-27, 2015 to strengthen the regional integration process, his proposals for having three agreements on road, rail and power (electricity) connectivity not only invited tough resistance from Pakistan as was expected, most of his unilateral gestures were viewed with skepticism in the region. Moreover, the South Asian countries including Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives expressed their willingness to induct China from an ‘observer’ status since 2007 to full membership in SAARC.

India’s Non-Military Response to Chinese Threat Perceptions

Due to its long-standing political and cultural penetration in the neighborhood, India believed it could manipulate internal political and cultural conditions within neighbors to foster its influence and undercut nascent Chinese foray into the region.

It kept anchoring certain political parties to maintain its dominance in the region, increased the amount of aid and extended lines of credit and quickly responded to humanitarian disasters in the region such as Tsunami affected South Asian countries – Maldives and Sri Lanka in 2006, earthquake affected Pakistan in 2005 and Nepal in 2015, relief assistance for Rohingya refugees to mitigate humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh 2017.

However, the nature of the assistance that India extended to its neighbors was bilateral and driven more by India’s concerns related to Chinese growing investment and influence in the region than any desire for removing the barriers to regional integration.

The South Asian Neighbors’ Security Perception

The neighbors while perceived threat to their sovereignty and territorial integrity from India’s neighborhood policy for long and many times took the form of resentment and statements suggesting India not to interfere in their internal affairs, China, a relatively new player in the region has not been viewed from this perspective.

As a result, the small South Asian countries either used the Chinese card to dissuade India from embarking on a robust regional policy or they allowed China a bigger role in the economic development and modernization of the countries. China’s mega connectivity project ‘OBOR’ received warm welcome from the small states as they saw a huge development potential from the initiative and some expressed their willingness to see China as a full member of SAARC.

While such pro-China gestures in the neighborhood is not seen favourably by India, small states are hard-pressed to walk a cautious path given India’s deep economic, political and cultural penetration in the region much before China’s entry. The Sri Lankan leadership, for instance, quickly responded to India’s security concerns on Chinese maritime strategy around Hambantota port facilities and made it clear that Beijing would limit its activities to commercial development of the port and no maritime strategies would be allowed.

When the Indian Prime Minister Modi made a visit to Nepal in May 2018, he received warm welcome from the communist leadership there despite recent history of animosity arising out of Nepalese accusations of India’s political interference in Nepal in the process of new Constitution-making and the irritant of economic blockade. Despite Bangladeshi regime’s invitation to China for infrastructural development, it turned to the Indian government for putting pressure on the government of Myanmar to take back Rohingyas in order to defuse the humanitarian crisis.

India’s Fixation with Chinese Threat is more Imaginary than Real

Notwithstanding the Doklam standoff, a war or direct military confrontations between the two countries is unlikely given the shifts in regional and global power configurations since 1962. The outcomes of the stand-off indicated India’s ability to project its power in the neighborhood cannot be challenged without serious risks.

India is not only a nuclear power, it has developed its conventional military capacities and naval presence to an extent which may not be to the proportion of projecting its power beyond the region but can defend the region. The Indo-US strategic relationship, India’s naval cooperation with Japan and Australia in the Indian Ocean along with the US can go a long way in tearing apart the ‘String of Pearls’ strategy of China. China’s foray into the South Asian region is of comparatively recent origin, while India has already deep socio-political and economic penetration into the region.

India enjoys a geostrategically better location to project its power in its immediate neighborhood and in the Indian Ocean than China. Perhaps, for all these reasons, India’s neighbors while resent its interference in their internal affairs, they remain vigilant to India’s security concerns and allow China a role limited to infrastructure development. Apart from this, the large volume of trade between India and China precludes the possibility of armed confrontation because that would not only sabotage existing trade and investment, prospects for trade relations would get suspended for an indefinite period.

China, which is predominantly an export-driven economy, has not only flooded the South Asian markets with cheap products, it has moved a large amount of capital in the shape of concessional loans to the South Asian countries for infrastructural project. The flip side of these projects is that when loans accrue without timely repayments these turn into debt-burden for the South Asian countries.

The projects ensure not only the Chinese companies are engaged in the infrastructure development works; all the raw materials and products necessary for the works are imported from China. When a South Asian country expresses its inability to repay loans, attempts were made to acquire land on lease as the Sri Lankan experience exemplifies. The Sirisena government of Sri Lanka leased out land to China for 99 years, under debt pressure, for the development of Hambantota port which aroused resentment from different quarters of the country. Pakistan, Nepal and the Maldives, on a few occasions, objected to the terms, conditions, negligence of local economy and modus-operandi of the projects. While the Chinese projects involve a huge amount of movement of capital, these may backfire in the long-run.

On the other hand, India’s aid to the South Asian countries is of lesser amount but they are targeted towards sectors like housing and railways with greater impact on local population.

According a World Bank report, around 5 million South Asian migrant workers in India sent more than $7.5 billion back to their home in the form of remittances in 2014; in the same year only 20 thousand South Asian workers in China sent a meager amount of $107 million back home. These statistics drive home the point that India’s economy and that of the South Asian neighbors is more organically inter-linked due to socio-cultural and geographical reasons than their economic linkages with the China’s export driven economy. Due to stronger economic linkages, India’s growth has a ripple effect on the South Asian countries.

For all these reasons, India should engage with its neighbors as a confident power and play a major role in the regional integration process instead of looking at the region from a security perspective. Many a times, its neighborhood policies largely dictated by a security perspective has led it to meddle in the internal affairs of the countries much to their chagrin.

South Asia: A Region of Hope and Despair

South Asia remains a region hope because it is the fastest growing region and shows prospects of further growth as findings of a recently released World Bank report indicated. Notwithstanding this optimistic note, the Bank’s chief economist for South Asia Martin Rama observed “the acceleration of growth that we see in the region is not necessarily that all countries are doing much better…..but given the size of India, India’s bouncing back is driving the growth”.

What this statement implied is as the negative fall outs of Demonetization and Goods and Services Tax (GST) policies in India gradually settled, it induced the regional growth to the top of the order given India’s size, population and remittances that migrant population of the South Asian countries generated. The average growth rate of other South Asian countries were below 6 per cent.

Despite registering robust growth rate, India is still facing serious challenges from all the non-conventional threats that affect others in the region. The primary reasons for this have been uneven distribution of resources within India and lack of regional and sub-regional integration within South Asia. Even achievement of a modest level of regional integration has the possibility of not only inducing growth rates, it can steer the South Asian economies towards inclusive growth by opening up larger market, keeping the rates of products low and providing different access points to avail health and education services. So far as the regional integration is concerned, South Asia provides a gloomy picture as it is one of the least integrated regions with intraregional trade accounting for only around 5% per cent of total South Asian trade.

India and its neighbors are fixated on state-centric or conventional threat perceptions as they see the source of threats to their sovereignty and territorial integrity only in powerful nations or in perceived aggressive moves of neighboring or external powers within the South Asian region. It is no gainsaying the fact that the region is home to many non-conventional threats like terrorism, poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, underdevelopment and illicit trafficking of people and drugs to name a few which can only be addressed through a non-conventional security perspective, regional integration and cooperative participation of extra-regional players in the regional attempts at handling these issues.

The noted journalist Kalyani Shankar has authored an excellent book , just released ,

on the same subject .Readers of Dr Mishra’s interesting article should also read

Kalyani Shankar’s book to get a full picture of a very important subject . Dr Mishra’s

approach provides a very relevant perspective and should be read together with

Kalyani Shankar’s analysis ….this is a vital area for India today and tomorrow .Not enough

attention has been given to it by scholars, analysts and policy-makers. Shankar ‘s very

comprehensive analysis and Mishra’s article should be carefully studied and be the

building blocs for further analysis and ongoing study of this area .