Why Birthright Citizenship Is Rare In Europe – OpEd

By MISES

By Ryan McMaken*

Luxembourg citizens voted in an election last year. But as The Economist has noted, “48% of those who live there were not allowed a ballot-paper.”

This is because a great many immigrants live in Luxembourg, but few of them quickly become citizens — which means few can vote.

According to the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX): “LU remains one of the most exclusive national democracies in the developed world, with the largest share of adults disenfranchised in national elections. According to 2013 OECD data, after 10+ years in the country, LU citizenship had been granted to only around 20% of the foreign-born, including among the non-EU-born, who are generally most likely to naturalise and see the benefits.”

Not surprisingly, The Economist thinks this is a bad thing.

Nevertheless, few are claiming that immigrants are treated poorly in Luxembourg. Because of Luxembourg’s small size and integration into the European economy, Luxembourg is quite open to migrant workers, both from neighboring countries, and from further abroad.1

Nevertheless, immigrants continue to flock to the country, and make up approximately 45 percent of the population. Moreover, 160,000 workers commute daily into Luxembourg from France, Belgium, and Germany — “Luxembourgers are only the majority in their country when the sun goes down.” In recent decades, many have become permanent residents.

Aware of complaints about a lack of more widespread suffrage in Luxembourg, voters in 2015 were given an opportunity to vote on expanding voting rights to foreigners in a referendum. 80 percent rejected the idea.

It should not be surprising, though, that many Luxembourg citizens are concerned that a sizable expansion of citizenship could bring about radical changes in Luxembourg through demographic shifts. A key strategy in slowing and managing this situation — while still allowing migration — is limiting access to citizenship.

A Case Study in Citizenship vs. Residency

The case of Luxembourg is helpful in illustrating how naturalization and immigration are two different phenomena. Clearly, experience suggests Luxembourgers are open to inviting in immigrants and working with them in a variety of economic ventures. Many live permanently in the country. The immigrants enjoy property rights and legal due process. A lack of access to political participation does not imply that it is legally or morally permissible in Luxembourg to treat immigrant property rights as forfeit. After all, immigrants have usually entered into legal contracts with employers and landlords to secure income, housing, and other types of property. Abolishing these legal rights could be disastrous for the local economy.

Moreover, the fact that the economy in Luxembourg depends on this openness to immigrants means the voting citizens are incentivized against enacting laws that might severely limit immigration or which would induce immigrants to avoid the country. Many Luxembourg voters likely are aware that — for practical reasons, if nothing else — it is not to their advantage to begin cutting off immigrants from their property. (It’s important to note virtually no one claims this widespread denial of voting prerogatives in Luxembourg constitute any sort of humanitarian crisis.)

Nevertheless, the response to Luxembourg’s practice of relatively open immigration — coupled with restricted citizenship — has some observers claiming the policy is tantamount to a violation of rights. Hence we hear charges of “taxation without representation” or the use of the often-loaded terms “disenfranchisement” and “democratic deficit.”

Should Citizenship Be Based on Location or Origin?

The idea that residents of a place ought to be quickly afforded full citizenship based on their current physical location, however, is far from universal.

Historically, policymakers, kings, and bureaucrats have long debated the criteria to be met in determining how quickly or how easily new residents ought to be offered naturalization.

For example, citizenship has been historically based on various criteria including residency, ancestry, promises of military service, and sworn oaths between individuals.

These criteria often fall into one of two legal traditions of naturalization: jus soli and jus sanguinis. Jus soli (“the right of soil”) is the principle that naturalization ought to be based on where one is located, and this often includes “birthright citizenship.” Conversely, jus sanguinis (“the right of blood”) is the principle that naturalization is based on one’s marriage, parentage, or origins.

Graziella Bertocchi and Chiara Strozzi have summarized the development of these two traditions in Europe and the Americas2:

In 18th century Europe jus soli was the dominant criterion, following feudal traditions which linked human beings to the lord who held the land where they were born. The French Revolution broke with this heritage and with the 1804 civil code reintroduced the ancient Roman custom of jus sanguinis. Continental modern citizenship law was subsequently built on these premises. During the 19th century the jus sanguinis principle was adopted throughout Europe and then transplanted to its colonies. … On the other hand, the British preserved their jus soli tradition and spread it through their own colonies, starting with the United States where it was later encoded in the Constitution.

The rise of jus sanguinis in Europe, perhaps not surprisingly, coincided with the spread of ethnicity- and language-based nation states in the nineteenth century. This in turn led to greater concern over whether or not migrants could integrate into each nation’s linguistic or cultural majority.

Thus, jus sanguinis requirements became an attractive means of slowing down the process of integrating new citizens and of ensuring that new migrant groups would integrate through native parentage, marriage, or through long terms of residency.

Europe vs. The Americas

The situation was very different in the Americas, however. It’s not a coincidence that we find the Americas to be far more reliant on the concept of jus soli.

Bertocchi and Strozzi note:

At independence, most of the incipient states [in Latin America] chose jus soli as a way to break with the colonial political order and to prevent the metropoles from making legitimate claims on citizens born in the new countries.

This is true enough. But it’s also true that far lower levels of population density, coupled with perennial labor shortages, made jus soli both more practical and more attractive to states in the Americas.

As Edward Barbier illustrates in his book Scarcity and Froniers, the Americas have long been characterized by a strong need for more laborers to take advantage of the vast natural resources present across the regions often sparsely populated lands. This led to a variety of immigration policies in the Americas designed to increase immigration. Argentina and Brazil, for example, paid migrants from Italy to settle in South America. Via the Homestead Acts in the nineteenth century, the US government offered free land to new migrants. And across the Americas, of course, many laborers were imported by force via the institution of African slavery.

The most-preferred strategy, however, was often to simply offer easy citizenship to new migrants, and to guarantee citizenship for the children of migrants via jus soli provisions.

At the same time, migration across borders has often been a challenge in many areas of the Americas. Many South American states are separated by deserts, mountains, and dense jungle areas. During the nineteenth century, crossing the Andes mountains was not a simple affair. Similarly, the borderlands between the US and Mexico were largely unpopulated prior to the twentieth century. Mexico’s population was concentrated in the southern regions of the country, and migration north required significant effort. It wasn’t enough to simply reach the border, either. Access to jobs and capital usually required an even longer journey north or west in the American interior.

Thus, by 1929, legal scholar James Brown Scott could write: “there is no American country which accepts that principle [i.e., jus sanguinis] as the sole test of nationality.” Since then, as the relative ease of migration has increased in the Americas, some regimes in the Americas — including the United States — have been pressured to pare back the dominance of jus soli provisions, although little have been done in terms of substantive change.

On the other hand, post-World-War-II Europe began to move away from jus sanguinis provisions. While Scott could conclude that just sanguinis was largely absent in the Americas, he also found “There are at present seventeen countries in Europe in which jus sanguinis is the sole test of nationality.”

Part of this was due to the higher population density and geographic compactness of Europe. Moving between political jurisdictions has long been relatively easy in Europe, compared to the Americas. Since the mid-twentieth century, however, the trend has moved toward greater use of jus soli. As of 2010, according to a study by Iseult Honahan,

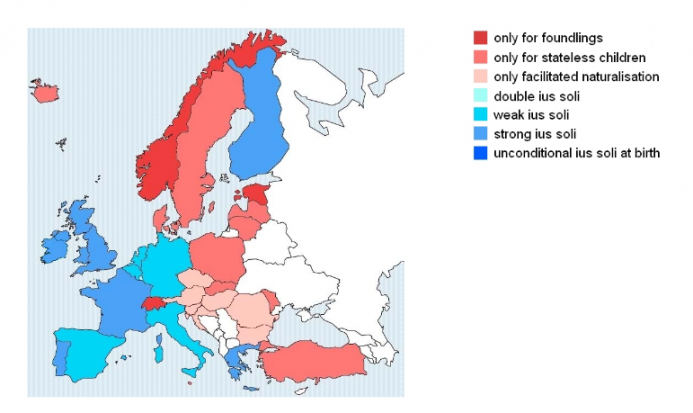

Ius soli citizenship is widely but by no means universally available in Europe. 19 European countries from 33 studied awarded ius soli citizenship at birth or thereafter. 10 of these countries grant ius soli citizenship at birth, and 16 after birth. … [I]us soli in its pure (or unconditional) form is not found in Europe since its abolition in Ireland in 2004.

There are, of course, a number of conditional jus soli provisions that exist. These can include automatic birthright citizenship for foundlings and stateless children. But many states have at least some weak jus sanguinis provisions requiring birth to at least one native citizen. Naturalization can occur outside of these conditions, but these provisions often require years of permanent residency, citizenship classes, and other mandates.3

Honahan concludes that the trend in Europe “is towards the wider availability of jus soli citizenship” but with many conditions attached in most cases. Europe-wide, jus soli provisions occur across a spectrum, with more strict provisions present in Eastern Europe and Switzerland:

Returning to our Luxembourg example, we can note that Luxembourg employs a “double jus soli” standard in which children born in Luxembourg receive automatic citizenship only if one of the parents was also born in Luxembourg. Honahan thus classifies Luxembourg as a jus soli country, but as we have seen, the situation in practice is one in which citizenship remains significantly restricted.

It is important to keep in mind, moreover, that the relative restrictiveness of naturalization law does not necessary reflect the restrictiveness of immigration law.

After all, Luxembourgers are frequently outnumbered by migrants, even if citizenship is restricted. Similarly, Switzerland has one of the largest populations of foreign-born residents in the world, yet is highly restrictive in terms of naturalization. Norway is similarly restrictive, although its foreign-born population is equal to that of the United Kingdom, which employs a more liberal jus soli standard.

This mismatch between immigration policy and naturalization policy highlights for us the fact that immigration has never been merely a matter of economic relationships. For example, among laissez-faire liberals, both Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard recognized that there is no economic argument against immigration. The situation is different, however, when we consider matters of citizenship and political participation. In these cases, migrants expand their role beyond the private sector and into the political sphere. As Mises noted, this fact — that fact that immigrants are not merely consumers or workers — carries with it a variety of complicating factors around the question of who shall be in control of the state. The smaller the state, the less relevant this question is. But in the presence of a robust state apparatus — especially one that controls educational institutions and social-welfare programs — this question becomes far more important.

Apparently, Luxembourgers are quite aware of these facts and have decided to maintain and expansive immigration apparatus while limiting citizenship. On the other hand, thanks to geography and the legal traditions of the New World, many Americans have a skewed view of the alleged inseparability between immigration and citizenship. This has clouded the American debate over birthright citizenship.

*About the author: Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for Mises Wire and The Austrian, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado, and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Source: This article was published by the MISES Institute

Notes:

- 1. In Luxembourg, as in much of the EU, naturalization law is a two-tier affair. Migrants who are already EU citizens have easier access to naturalization than non-EU citizens from places like Africa and Asia.

- 2. See working paper: “The Evolution of Citizenship:Economic and Institutional Determinants” by Graziella Bertocchi and Chiara Strozzi. December 2005. (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.540.4022&rep=rep1&type=pdf)

- 3. The extent to which jus soli provisions are adopted is not necessarily synonymous with ease of naturalization. For example, the United States could abolish birthright citizenship while also expanding naturalization through other means. On the whole, however, the degree to which jus sanguinis requirements are employed generally reflects a regime’s overall openness to expanding citizenship quickly and easily. Notable exceptions exist, such as Sweden, which is restrictive in terms of just soli, but has permissive naturalization-by-application policies.