Ali And Nino’s Enduring Mystique – Analysis

By Evolutsia

Kurban Said’s classic Ali and Nino has become a kind of literary calling-card for the South Caucasus region. Emma Pratt explores the novel’s powerfully enduring message.

By Emma Pratt

The novel Ali and Nino by Kurban Said has become the book to read before visiting Georgia, despite the fact that it is set in Azerbaijan and was originally written in German,. The book is displayed in the regional section at Prospero’s Books in Tbilisi, has lent its characters’ names to a statue of two lovers in Batumi, and, according to Thomas Goltz (the author of Georgia Diary), was required reading for Alex Rondeli’s students interested in Georgian politics.[1] The novel is frequently cited in the news when ethnic conflicts break out in the Caucasus and Foreign Policy magazine listed it as one of “The foreign-policy books you should be reading to get ready for election season”. A novel of love and war set at the beginning of the twentieth century, Ali and Nino remains relevant to the often-tumultuous political situation in the Caucasus, which is part of the reason it continues to be popular today. Ali’s brave and well-reasoned defense of his beloved homeland and his acceptance of other cultures make him a positive hero for the Caucasus. These honorable characteristics still resonate today, making Ali a model hero for the region in post-Soviet times.

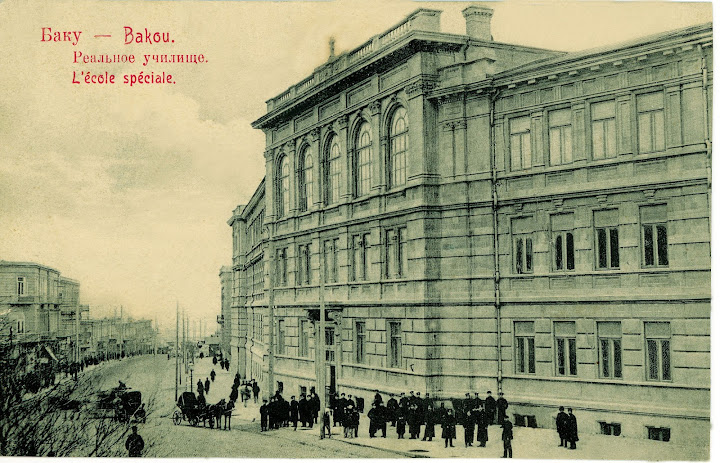

One of the mysteries of Ali and Nino is its authorship. “Kurban Said” is known to be a pseudonym, but the author’s true identity has been a subject of widespread speculation. Some suggest that the author was the Austrian Baroness Elfriede von Ehrenfels,[2] while others assert that it was written by the Azeri nationalist poet Yusif Vezir.[3] Following the publication of Tom Reiss’ 2005 investigation of Ali and Nino’s authorship, The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life, most accept Reiss’ assertion that the author of the novel was Lev Nussimbaum. Nussimbaum was a Russian Jew who was raised in Baku and exiled to Berlin following the Bolshevik Revolution.

Ali and Nino is set in Nussimbaum’s home city of Baku at the dawn of the First World War. The young Azeri nobleman Ali Khan Shirvanshir falls in love with the Georgian schoolgirl Princess Nino Kipiani and the two plan to spend their summer together in Karabakh. However, their plans are interrupted by World War One. As a Muslim, Ali is not subject to the tsarist draft and thus can decide if he wants to participate in the war. Though his friends enlist, Ali takes time to ponder his options and chooses to stay home. Ali and Nino’s courtship continues and the two agree to marry, though their Armenian friend Melik Nachararyan has to convince Nino’s father to allow the marriage. He does so by pointing out that this marriage of will be politically beneficial as a symbol of friendship among the peoples of the Caucasus.

One evening, Ali is unable to take Nino to the opera as he promised, so Nachararyan escorts her instead. Following the performance, Nachararyan “bride-naps” Nino. Ali sets off after them. Tradition requires that he kill both Nachararyan and Nino to salvage his honor. Ali kills Nachararyan with his bare hands, but breaks tradition and spares Nino’s life. Nachararyan’s death sparks a blood feud between his family and Ali’s. While in exile in Dagestan avoiding the feud, Ali and Nino marry in secret and live happily together until they receive the news that the war has spread to Baku. They return immediately.

Ali defends Baku, but when his side is defeated, the young couple is forced into exile with Ali’s extended family in Tehran. Nino is unhappy with the restrictions she faces in Iran, and is eager to return home. When the Baku is liberated and Azerbaijan becomes independent, they are at last able to return. In Baku, Ali begins a career with the government of Azerbaijan and their daughter is born. Their happiness is short-lived, however, as the Bolsheviks attack Ganja, where the family is vacationing, and it becomes the last stronghold of independent Azerbaijan. Ali takes up arms in Azerbaijan’s defense and is killed in the battle.

***

Ali’s decision not to participate in World War One makes him a relatable hero for the modern Caucasus. In the novel, Ali writes: “My first impulse [was] to go to war as soon as possible. Now I had time to think…There was no enemy in my country. No one threatened Transcaucasia’s steppes. Therefore this war was not my war.”[4] Ali does not join the military for glory or to kill. He shows self-restraint, and saves his participation for when he must defend his home, an honorable cause. Ali’s participation in war is the result of decisions and convictions, not chance or emotion.

Ali only begins to use force in response to Nino’s kidnapping. After Nino is taken from him, forcing him to fight Nachararyan and take his friend’s life, Ali is transformed into a warrior, and is thereafter willing to fight for those things he loves—both his Nino and his homeland. Even before his involvement in the blood feud, Ali believed that he would only take up arms when he was personally affected by the circumstances. He says, “Only when the invisible one attacks my world—only then will I draw my sword.”[5] The first attack on his world is Nino’s kidnapping, and by rescuing her, Ali goes to war. This parallel between war and Nino’s kidnapping is drawn in the novel by the symbolism of the horse that Ali uses to rescue Nino. Ali, and the readers, have been told, “Only when war breaks out does the owner mount his red-gold miracle.”[6]

After Ali kills Nachararyan, his warrior side is awakened, and from that point on he participates in the defense of his homeland. Ali’s battles expand from protecting Nino to protecting his homeland. The parallel between defending Nino and defending Azerbaijan is illustrated by Ali’s understanding of Nino as home. He writes, “Other people will say I stay at home because I do not want to leave Nino’s dark eyes. Maybe…For to me those dark eyes are my native earth, the call of home to the son a stranger tries to lead astray. I will defend the dark eyes of my homeland from the invisible danger.”[7] After he defends Nino, Ali is transformed and becomes a defender of his homeland of Azerbaijan and in particular his city of Baku.

Ali participates in two battles: the defense of Baku and the last stand at Ganja. He does not hesitate to participate in either. When Nino asks if he will join the fighting in defense of Baku, his answer is simply, “Of course, Nino.”[8] Likewise, Ali stays and fights in Ganja, though he recognizes that the situation is dangerous and he is unlikely to live. Before the battle begins, he sends Nino and their infant daughter away to safety in Georgia. Once Ali has committed himself to the cause of Azerbaijan’s defense, he does not back down, as his last thoughts illustrate. “In a couple of hours I will again be standing on the bridge. The Republic of [Azerbaijan] has only a few more days to live. Enough. I will sleep until the trumpet calls me to the river again, where my ancestor Ibrahim Khan Shirvanshir laid down his life for the freedom of his people.”[9]

Ali is loyal to his country, and his devotion to Azerbaijan is absolute. Though he is given the chance to live peacefully in Iran, he does not take the opportunity. He instead returns to troubled Azerbaijan in order to serve his country, and only his country. When his cousin asks him to stay in Iran and work for its benefit, Ali replies “I cannot build Iran. My dagger was sharpened on the stones of Baku’s wall.”[10] Ali is not eager to engage in every battle or nation-building campaign possible. It is only for his country, Azerbaijan, that he is willing to expend his sweat and blood. Ali makes the ultimate sacrifice for his country, and gives up his life with Nino and their daughter in favor of his love of his country.

***

One aspect of Ali’s support for the Azerbaijani state comes from Lev Nussimbaum’s dislike of revolutions and the chaos and murder that often accompany them. Reiss explains, “The chilling suggestion to ‘kill all those foreigners who talk and pray differently from us’ is at the heart of Lev’s small masterpiece, Ali and Nino. It is why Lev came to hate revolution on principle: it was too easy a pretext for mass murder.”[11] Ali’s ability to accept difference is a factor of the multiple cultural influences which affect him as a citizen of Transcaucasia. He is devoted to his homeland, and this homeland is a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state, so though Ali has his prejudices he also exhibits a basic level of tolerance towards others. He has friends from other cultures, and even in his most violent actions he is motivated by love, not hate. Ali’s love of Nino, a Georgian Christian, shows his acceptance of other cultures. He marries her, allows her to furnish their house in European fashions, does not ask her to wear the veil, and acquiesces that their daughter will be raised Christian and European. His friendship with Nachararyan (before the kidnapping) is another example of his tolerance. Ali offers to hide Nachararyan in his house in the event of ethnic-based violence against Baku’s Armenians.[12] Even though Ali ultimately kills Nachararyan, the killing is in retaliation for a personal slight, not due to a hatred of his race or a desire to kill all Armenians. Ali is not a perfect model of tolerance, but he demonstrates despite his prejudices, he is capable of acting in a tolerant manner and developing relationships outside his ethnic and religious group. Ali is opposed to the categorical discrimination against a particular ethnic group, and says, “Isn’t it stupid—this hatred for the Armenians.”[13]

Ali’s end comes as he is defending his beloved homeland against the Russians. The power and inevitability of Ali’s end are a large part of what makes the story resonate with contemporary readers. Ali’s death at the hands of the Bolsheviks parallels contemporary fears of a Russian invasion. It illustrates that Russia has always been a formidable and dangerous enemy. Ali and Nino is anti-Russian and anti-revolution, but Ali’s actions elevate him beyond the traditional construction in Russian literature of the savage hero of the wild Caucasus.[14] Ali is depicted as a man who loves his country and his culture—a patriot—but not one who is dangerously nationalistic or intolerant of difference. The ideas celebrated in the book, defense of one’s family and homeland and love of one’s culture while tolerating others, make the story relevant for a region that is still struggling with the ghosts of past ethnic conflicts and Russian aspirations toward greater influence. Through his love of his country, Ali becomes a hero of the Caucasus.

Emma Pratt has an M.A. in Slavic and East European Studies from The Ohio State University where her research focused on Georgian politics and culture. She currently lives in Kakheti.

Notes:

1. Goltz, Thomas. Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter’s Adventures in an Oil-Rich, War-Torn, Post-Soviet Republic. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1998. Print. p. 115.

2. Reiss, Tom. The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and a Dangerous Life. New York: Random House, 2005. Print. p. 303.

3. Clemons, Walter. “The Last Word: Who Wrote ‘Ali and Nino’? ” Rev. of Ali and Nino. New York Times (1923-Current file) 27 Jun 1971, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 – 2007), ProQuest. Web. 27 Feb. 2011.

4. Said, Kurban. Ali and Nino: A Love Story. Trans. Jenia Graman. New York: Anchor, 2000. Print. p.72.

5. Said, 73.

6. Said, 44.

7. Said, 73.

8. Said, 187.

9. Said, 275.

10. Said, 219.

11. Reiss, 60.

12. Said, 112.

13. Said, 108.

14. See Layton, Susan. “Imagining the Caucasian Hero: Tolstoj vs. Mordovcev.” The Slavic and East European Journal 30.1 (1986): 1-17. JSTOR. Web. 20 Feb. 2011. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/307274>.