Did Tokayev Provide Putin With A Good Excuse For ‘Causing A Great Inconvenience’ To Kazakhstan, Europe? – Analysis

For quite a long time, the Kazakh ruling elites have managed to ensure a balance between the interests of Moscow and the West concerning Kazakhstan. And so far, they’ve been not bad at it. But as time passes it gets harder and harder for them to remain on that path. So one day, the possibilities of being ‘on the same page’ with both of these parties at the same time may be completely exhausted. Judging from the current developments, that is what seems to be happening right now.

Here is what Moskovskaya Gazeta, in an article entitled ‘How can Moscow react to the apparent disloyalty of Kazakhstan’, said in regards to this: “Political analysts believe that compliance with anti-Russian sanctions is incompatible with being the EAEU and the CSTO member, so Kazakhstan will soon have to make a choice on which side of the confrontation [between the West and Russia] it will be. ‘Going both ways’ apparently is no longer an option”. The US ban on purchases of oil and natural gas from Russia and the EU leaders’ decision to block most Russian oil imports by the end of 2022 to punish Moscow for invading Ukraine could jeopardize not only the activities of American and Western European energy companies extracting crude hydrocarbons from the fields in Western Kazakhstan and delivering them mainly to the EU countries, but also the socio-political and economic situation in the Central Asian country. Such a danger is taking increasingly real shape and becoming an important factor when considering various scenarios for the development of the situation that may arise in the relationship between Kazakhstan and Russia, on one side, and Kazakhstan and the West, on the other.

It is unlikely that Moscow can sit by idly while it sees the Westerners continuing to deliver – via the pipelines running through Russia – all of Kazakhstan’s oil produced by Western investors to the their own markets in conditions where access to the latter ones is almost completely denied for Russia. But what, exactly, is to be expected?

To hear the overseas political experts tell it, Russia is willing to go to great lengths with regard to the neighboring Central Asian country – going as far as to interfere in its internal affairs. As if anticipating such a scenario, Walter Russell Mead, the Global View columnist at the Wall Street Journal, insists that ‘the US should curb Moscow’s clout in its highly dependent and oil-rich neighbor’. That’s easier said than done.

When viewed from the European side, Kazakhstan is seen as a country situated behind Russia, engaged in an explicit conflict with the US and other Western states over Ukraine. And the answer to the question of whether the European Union which has adopted a decision to ban the bulk of imports of Russian crude and oil products, will be able to continue getting oil, without any impediments, from Kazakhstan via Russia, depends on the will and interests of Moscow, isn’t it?

The Kremlin, through its top diplomat Sergei Lavrov, has said that ‘the West has declared a total war on us, declared a total war on the entire Russian world’ and that ‘this situation will last for a long time’. In view of such prospects, there seems not to be much reason for the united Europe to expect to continue getting oil, without any impediments, from Kazakhstan.

By the way, the problems are already there. The week before last, Russian authorities shut down the Black Sea terminal that handles two thirds of Kazakhstan’s oil exports in order to find unexploded ordnance on the seabed. It was earlier expected that this task would only take a few days.

But Russia’s energy ministry said recently that the search for explosive mines near the Caspian Pipeline Consortium’s (CPC) Black Sea terminal would be completed by July 5, extending the completion date from June 25. That’s not the first time that’s happened. The CPC suspended oil loadings in March after damage to the loading facilities due to stormy weather in the Black Sea. That move contributed to a global oil prices increase. The CPC pipeline which transports oil from fields in Western Kazakhstan to the marine terminal on Russia’s Black Sea coastline, near Novorossiysk, and is partly owned by US oil majors Chevron and ExxonMobil, exported 53 million to 54 million tons of Kazakh crude last year. Here is what was said in the Handelsblatt newspaper about the March incident with the CPC loading facilities: “The alleged storm over the Black Sea caused great inconvenience to Kazakhstan and Europe… Oil transit through the pipeline was disrupted. The only odd thing is that, according to Germany’s National Meteorological Service, the wind conditions on those [relevant] days were not unusual for the region”.

It therefore seems understandable why earlier Nina Khrushcheva, a professor of international affairs at the New School in New York, saw fit to warn about the dangers of serious complications for the Western investors working in the western part of Kazakhstan. According to her, “if Putin has a political and economic say in Kazakhstan, then it would be infinitely difficult for them [US oil companies, like Chevron and ExxonMobil] to function and sort of not take Russia into account”. The point is this is already happening.

It turns out that the Kremlin only needs one thing to create in Russia’s near abroad a situation in which it could dictate terms to the West, and not the West to it. And that is ‘having a political and economic say in Kazakhstan’. But what would it mean? Just as in the case of Ukraine earlier, it is difficult to speak specifically about possible scenarios in this regard.

No one could have anticipated full-scale war in Ukraine. But it broke out between the Russian Federation and Ukraine and has been going on for the fifth month. Nobody can tell you how long the war will go on. The Kremlin propagandists and political analysts say that the war must be ended in victory by all means. Against such a background, it is curious to note that there has not so long ago been a much stronger belligerent and offensive (if not just aggressive) attitude towards Kazakhstan, than towards Ukraine, among those who form Russian public opinion.

On 20 August 2021, the hosts and participants of Russian Channel One’s Vremya Pokazhet talk show considered the possibility that Kazakhstan would be on the way of falling apart, and one of the latter, Yakub Koreyba, a Polish political scientist, expressed the view that ‘collapse [instigated from abroad – as one might assume] of Kazakhstan would be a disaster, a geopolitical disaster for the West”. And ever since then, public personalities and politicians have been unabashedly discussing different options for transforming Kazakhstan in the Russian media. What is important here is that in doing so, they seek to justify those evil schemes concerning the Central Asian country by blaming its leadership’s foreign policy. Here is just the latest blatant illustration of that. EAdaily.com, in an article entitled ‘Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy might tear it [the country] apart’, quoted Sergey Pereslegin, a Russian political analyst and futurologist, as saying that ‘maintaining the unity of Kazakhstan is a [complex] art. Yet what they (the Kazakh authorities) have been doing lately is playing a kind of the giveaway. This is quite a bad choice’. It is, according to him, threatening to become a trigger for ‘tearing it [the country] apart’. Sergey Pereslegin believes that Kazakhstan is artificially putting itself in a position where the national government and the different parts of the country would gravitate to various external centers of power.

In Russia, there are various opinions from among political analysts, journalists and politicians on what might be the basic implications of such development in Kazakhstan. Some of them believe that the ‘internal problems’ of that Central Asian republic ‘can be solved’ by ‘transforming it into a federation’, since allegedly ‘the root of its current tragedy lies in the remnants of the tribal system, which have been coupled with the unitary form of government‘, and it [the country] is ‘very is clearly divided into three parts: Northern, Southern and Western ones, where three Kazakh zhuzes – Middle, Senior and Junior ones – have traditionally and compactly lived’. Others are of the view that in the present situation, ‘there are two options for Russia: the first is to move the actual state border of the Russian Federation southward [at the expense of Kazakhstan] as far as possible – along the line: ‘Balkhash – Baikonur – Bekdash’; the second is ‘to federalize Kazakhstan through the creation of two super-regions – ‘the Northern’ and ‘the Southern’ along the line ‘Ural – Ishim – Irtysh’. (As a matter of fact, both of those projects, developed by the Russian strategists, provide Moscow’s interference in Kazakhstan’s territories).

A lot more direct is State Duma deputy Mikhail Delyagin, when speaking on this matter: “Unless Northern Kazakhstan, along with Central and Western Kazakhstan, rejoins their Homeland [Russia] as a result of the upcoming events, it will be … well, like ditching Donbass (non-admission of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic to Russia]… And let mambets [ordinary Kazakhs] and akims [their leaders], being left without a penny, eat each other on a patch [that would left there, according to M.Delyagin, after the suggested annexation of Northern Kazakhstan, Central and Western Kazakhstan by Russia] of ‘historical Kazakhstan’ – the others’ ethnic traditions should be respected”.

All of those proposals – or options – involve partial or complete removal of the regions, where the Middle and the Junior zhuzes have traditionally lived, from the control of the Senior zhuz elites. At the same time, the special form of closeness of the northern Kazakhs to the Russians, in contrast to the southern Kazakhs, is being stressed: “We need to pay more attention to protecting… the Kazakhs from the Middle Zhuz, who are historically and mentally close to us.

The southern region also needs support in restoring order, but let the Kazakh authorities manage that situation on their own”. There is also an emphasis on the inequality of Western Kazakhs in comparison to those from the South: “The country is commanded by the Senior Zhuz, whereas the people of the Junior zhuz are working,” and “their leaders believe that this is unfair, because oil and gas are on their traditional land, while people from Alma-Ata are in command”; “the poor West”, that has been and still is contributing as donor to all the other regions which rely on subsidies from the republican government.

In other words, the Russian political analysts, journalists and politicians are already verbally drawing the dividing lines, bearing in mind the prospect for the alleged collapse or federalization of Kazakhstan. There is nothing new here. They have been doing this kind of thing with respect to Ukraine all those years. These people now seem to be wanting the infamous policy of ‘divide and rule’ to be applied to Kazakhstan, however not by opposing the ‘European’ and/or ‘Pan-Turanian’ ideas to the ‘Russian world’ ideology and/or the ‘post-Soviet Eurasianism’ concept, but through making moves leading to a clash of interests among Kazakhs divided into three zhuzes. To the same end, they consider publicly different options for transforming Kazakhstan. All this is being done with complete disregard for the fact Kazakhstan, just like Russia itself, is a founding member of the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). There’s a simple explanation for that. Back in 2003, Russian journalist Pavel Voshchanov, in his article entitled ‘Kremlin show: Name that tune of the elections’, predicted: “[It may be confidently predicted on the eve of elections, that] everything will focus on one theme: the omnipotence and arrogance of America. Mildly – so as not to annoy Bush too much – Russian voters will be asked to approve a new political doctrine, essentially as follows: Russia Uber Alles! This means that its national interests must be well protected not only from enemies, but also from partners… It cannot be otherwise since ‘Our Motherland is in danger!”. That was a long time ago. Yet Pavel Voshchanov’s prediction still sounds fresh.

All those scenarios for the future of Kazakhstan of the above kind, of course, have been and are being viewed through the lens of the Russian interests which ‘must be well protected not only from enemies, but also from partners’, like Russia’s Central Asian neighbor. What, indeed, are the causes for such biased attitude towards the Republic of Kazakhstan among political analysts, journalists and politicians in Russia? We tried to find out the answer to this, and here is the result.

In mid-January 2022, Ukraina.ru, in article entitled ‘Ukraine is not Kazakhstan, that’s why Russia will fight for it [the Republic of Kazakhstan] until the very last’, quoted Andrey Grozin, the head of the Central Asia and Kazakhstan department in the Commonwealth of Independent States Institute, as saying the following: “The problem is that [Kassym-Jomart] Tokayev is being seen as a person who wants to be friends with everyone and is afraid to ruin relations with everyone.

Ukraine, with all its nonsense, is a kind of nuisance, but you can live with it. And Kazakhstan, which is run by Russia’s enemies or is not run by anyone at all (the latter is the most likely one of the bad scenarios), is something, we mustn’t even think about. Should that happen, we will have to deploy not peacekeepers to the [neighboring Central Asian] country, but a real military contingent, in order to take control of the logistics hubs simply so that we retain access to the south [the other four States of Central Asia]. Or else there will be, if you will permit the vulgarism, a complete and total ass.

We will somehow get through with the insane Ukrainian authorities, if not this year, then next. Yet this is just a small piece of geography. [While] Kazakhstan is the ninth largest country in the world in terms of area. There is the 7,500-kilometre (4,750 mi) of unguarded border between them [the Republic of Kazakhstan] and us [the Russian Federation]…

We can’t wall ourselves off from Kazakhstan, even if we wanted to. Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova are countries, which are important to Russia. I mean, in terms of ideology, economy and military potential. As for Kazakhstan, it is different. It is kind of like Ukraine presented in a concentrated form”.

In Russia, serious observers, dealing with the Kazakhstani issue, agree that Mr. Tokayev is the person who is inclined to make concessions and avoid creating controversy, while looking for some kind of consensus, which can be read as an expression of weakness of character in Asian societies. Then the question becomes where this may lead. According to some of those observers, the question of whether he can rule on his own remains open. For others, the current policy [and methods] used by the Kazakh leadership ‘might tear it [the country] apart’. Yet, as might be assumed, the Russian side also wouldn’t mind capitalizing on Mr.Tokayev’s penchant for compromise for their own benefit. And here’s what the story is.

Kazakhstan’s main oil exporters are now going through three-week-long outage at two of the CPC terminal’s three marine loading buoys, near Novorossiysk. This situation, created by the relevant decision of the Russian authorities, raises questions about what could be the actual cause behind it. Shutting-down the Black Sea Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) terminal because of dozens of potential pieces of unexploded WW2 ordnance discovered near it, that isn’t very convincing, is it? Doing so in response (if not in punishment) to the Kazakh leader’s statement at the plenary session of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, that’s quite another matter. Such causal link as an explanation for the above decision by Russians looks much more believable.

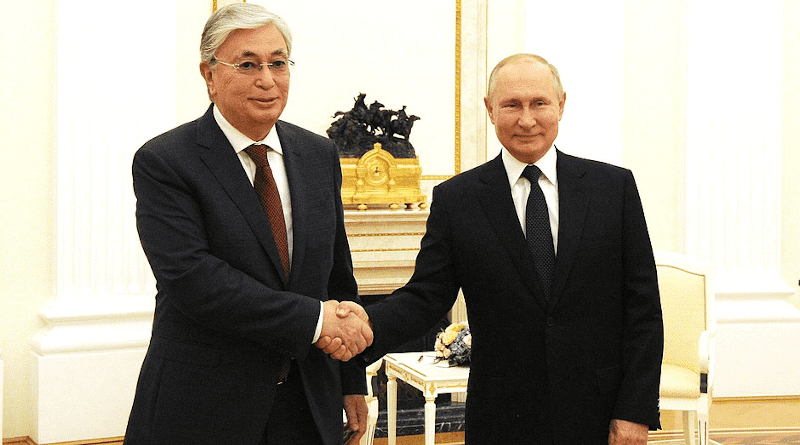

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s dissent with the position of the Russian Federation on the issue of pro-Moscow separatist movements in several former Soviet republics is on one side of the scales. On the other side of the scales is provision of the Kremlin with a good excuse for ‘causing great inconvenience to Kazakhstan and Europe’. Which of them is worthier or, say, weightier? The answer is obvious. While speaking at the 25th St Petersburg International Economic Forum, the Kazakh leader didn’t say anything new. He merely reiterated the position of his administration that it would not, recognize Donetsk and Luhansk, the two eastern regions of Ukraine that are mostly under the control of Russia’s occupying armed forces, as independent republics. In a March 29 interview with Euractive’s senior editor Georgi Gotev, Tokayev’s first deputy chief of staff, Timur Suleimenov, said: “Kazakhstan will not be a tool to circumvent the sanctions on Russia by the US and the EU. We are going to abide by the sanctions. Even though we are part of the Economic Union with Russia, Belarus and other countries, we are also part of the international community. Therefore the last thing we want is secondary sanctions of the US and the EU to be applied to Kazakhstan”.

“Of course, Russia wanted us to be more on their side. But Kazakhstan respects the territorial integrity of Ukraine. We did not recognize and will not recognize the Crimea situation and neither the Donbas situation because the UN does not recognize them. We will only respect decisions taken at the level of the United Nations”, he added.

P.S.: This whole thing with what Mr. Tokayev said, responding to a question from Russian propagandist Margarita Simonyan about Russia’s war against Ukraine, appears to have been inspired by the Russian political strategists. If Kazakh officials had the choice to decide in this case, they would not have agreed to such an interview with Mr.Tokayev by RT’s editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan, who, according to Russia’s Novaya Gazeta newspaper, had earlier exhibited racist behaviour towards Kazakhstan and the Kazakh people, verbally attacked official Nur-Sultan for not being willing to follow Moscow’s lead, and whose husband, television show presenter Tigran Keosayan, went further in April, unleashing a tirade against Kazakhstan’s leadership that was so vicious the foreign ministry pledged to bar him from the country.