South China Sea Arbitration: Court Rules, But Who Will Enforce The Writ? – Analysis

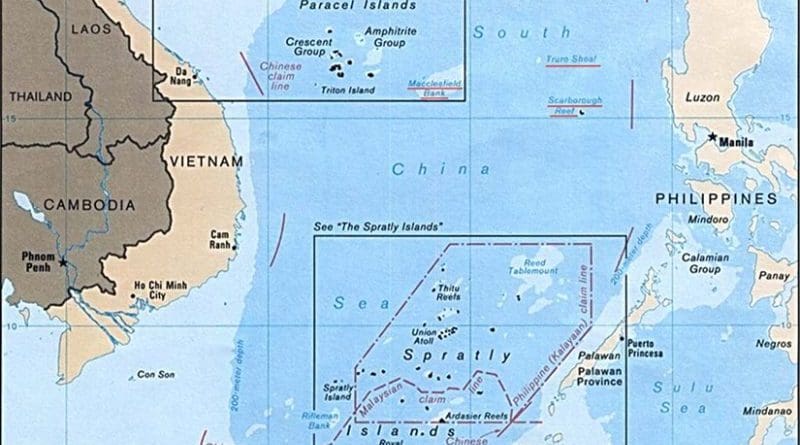

On 12 July 2016, the Tribunal constituted under Annex VII to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) located at The Hague in the Netherlands passed judgement on the case of the Republic of the Philippines V. the People’s Republic of China. The Award, concerning the historic rights and maritime entitlements of both the nations in the South China Sea was unanimous and almost entirely favoured the Philippines.

The Philippines had lodged the suit against China on 22 January 2013 in the international court. For the previous 17 years it had attempted to defend its legitimate maritime rights through political and diplomatic avenues and had been repeatedly beaten back. Only after exhausting all other means did it take recourse to International Law. While other nations in the South-East Asian region also have issues of sovereignty with China, none have so far dared to approach the Tribunal. The Philippines views China as yet another imperial power trying to browbeat it and its action must be seen as the manifestation of desperation on the part of a small nation.

China, on the other hand, had tried to pre-empt the ruling of the Tribunal going against it with a media campaign, while also offering to hold bilateral talks with the Philippines. It has harked back to an agreement with the Philippines, signed in 1995, where both parties had agreed to settle all differences and disputes through negotiation. Even before the ruling was given, China had stated that it would ignore the verdict, knowing fully well that the Tribunal has no authority or capacity to enforce the writ. Further, China claims to have the support of 40 nations for its stated position that supports bilateral negotiations. During the arbitration process itself China had officially stated that ‘…[it] will neither accept nor participate in the arbitration unilaterally initiated by the Philippines’. However, under the UNCLOS it is not necessary for all parties involved to participate in the process. It is the responsibility of the Tribunal to satisfy itself that the claim being investigated is well-founded in fact and law.

That was the course of action adopted in this particular case.

Over the past few decades, the South China Sea has become a resources battleground; it is estimated to have 11billion barrels of oil, 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and to account for 12 per cent of global fisheries catch. While being energy rich, it is also strategic waters with $ 5.3 trillion sea-borne trade passing through it every year.

The Ruling

The Tribunal provided rulings/findings on five major issues. (This analysis does not go into the legal intricacies of the judgement.) One, historic rights and the nine-dash line: the Tribunal concluded that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources in the areas that fall within the nine-dash line. Two, status of features: it was judged that none of the features claimed by China was capable of generating an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and also that certain sea areas claimed by China were within the EEZ of the Philippines since those areas are not overlapped by any possible Chinese entitlement. Three, lawfulness of Chinese actions: it was decided that China had violated the Philippines’ EEZ and its sovereign rights, by interfering with Philippine fishing and petroleum exploration, through the construction of artificial islands, and by failing to prevent Chinese fishermen from fishing in the zone. Four, harm to marine environment: it was arbitrated that China had caused severe harm to the coral reef environment of the South China Sea through the recent large-scale land reclamation and construction of artificial islands. Five, aggravation of dispute: it was assessed that Chinese activities, like building a large island within the Philippines’ EEZ, were incompatible with the obligations of a state during dispute resolution process and arbitration proceedings.

China stated that by referring the case to the Tribunal the Philippines had acted in bad faith and that China does not accept any means of third party dispute settlement on territorial and maritime delimitation disputes. The official statement from China was that ‘PRC solemnly declares that the award is null and void and has no binding force. China neither accepts nor recognises it’. With this declared stance from China, the world woke up to the fact that asserting the right and wrong of a nation’s position and providing an emphatic judgement was easily done; upholding and enforcing the ruling and establishing adherence to International Law was another matter altogether.

The Meaning of the Judgement

What does this forceful judgement mean? To China, the USA, and the rest of the world? The judgement is a statement by experts in International Law that China’s extensive maritime claims are considered outrageous and the evidence dubious. The island building spree that China has engaged in was dismissed as attempts to change the status quo. The ruling also invalidated China’s historic claim as the legal basis for the nine-dash line upon which a great deal of its claim was built. This is a great loss to China. Therefore, while the ruling is legal, in all probabilities China will tend to ignore it. China’s initial reaction has been vehement and points in this direction. The Chinese claim of being a peaceful rising power has clearly taken a beating.

International Law is unambiguous on the fact that no nation can unilaterally alter the status quo to suit its own purpose. In this instance the ruling is seen as a victory for the advocates of the status quo in the South China Sea. Status quo in the greater Asia-Pacific region is a prerequisite for the regional nations to continue on a path of peaceful development to prosperity. The judgement is therefore also a victory of sorts for the smaller regional nations who lack the ability to contain and push back against coercive Chinese overtures. In a nuanced manner the arbitration has created an international public opinion perception of China being an aggressive power, regardless of its statements of peaceful intent. It also opens a limited pathway for other small nations to pursue in the future. However, China’s medium and long term reaction to the ruling will be the key to future prospects of peace.

The Chinese View

China continues to suffer from a sense of national violation because of the events that took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This feeling is coated with a large dose of self-righteousness in most international dealings. It is not surprising that the Chinese claims in the South China Sea are not based on history alone, but equally on an emotional interpretation of the need for its control. The South China Sea is an emotive issue for China and this feeling is unlikely to change in the near future. The Tribunal ruling is already being portrayed in the domestic media as yet another attempt at humiliating China by vested ‘Western’ interests. Anti-Western rhetoric, already at a high point, is being fuelled further.

Over a period of the past five to six decades, China has managed to perpetuate a domestic belief that the South China Sea historically belonged only to China. This is blatantly wrong. History proves that the South China Sea was always a shared area and that China was only one of the nations that used the sea. The exclusive claim that China puts forward now as ‘historic’ only emerged in the dying years of the Qing Empire and the chaotic early years of the formation of the Republic of China. The current stand-off with other nations regarding the contested sovereignty of the South China Sea has been created by China’s assertion of its entitlement to sole possession, buttressed by belligerence, aggressiveness and the flexing of military muscle. Obviously, none of these actions have been well-reveived by the smaller South-East Asian nations.

Although it is claiming global super power status, for some unfathomable reason China continues to play the part of a wronged nation. It continually refers to the ‘century of humiliation’ during the Qing dynastic rule. This victimised stand is in direct contrast to all its other actions, all of which indicate the offensive stance of an arrogant and powerful state. China states that only it knows the ‘true’ interpretation of the UNCLOS and accuses the Philippines of violation of its sovereignty, which is in complete contradiction of the court’s ruling. There is a theory of a multifaceted conspiracy against China being propagated for domestic consumption and claims that the US is attempting to ‘contain’ Chinese rise to power being made. Immediately after the verdict was issued, China has made vague threats of going to war if other nations do not back off in the South China Sea. It has also put out contrary indications by taking part in the biannual, US-led Rim of the Pacific exercise while announcing a joint exercise with Russia one day prior to the announcement of the judgement.

The current untenable situation is almost completely the result of Chinese actions. However, it must be admitted that in a nation like China, policy reversals cannot be achieved overnight. Reorientation will take time and some analysts see a softening of China’s stand. They advocate giving China time to ‘save face’ and move gradually to a path that is in compliance with International Law. However, based on past history and the trajectory that the current administration has so far set, there can be no assurance that China will adopt this optimistic path and accept the Tribunal ruling in the long term. At least for the time being, the opposite course of action is what is being indicated.

China’s Challenges and Choices

The differences between China and its neighbors around the South China Sea widened perceptibly after the Tribunal gave its ruling. This was primarily because of the hasty reaction that the Chinese resorted to and the strong unilateral position that it adopted.

It will be difficult for the Chinese Government to climb down from that perch or rescind the already proclaimed policy statements. The court ruling on the South China Sea issue now poses challenges to China at all levels—at the domestic arena, the issue has been repeatedly portrayed as relating to the sovereignty of the nation; regionally, China has adopted an uncompromising stand in bilateral and more so in multilateral relations with neighbours; and internationally, it has already thrown its hat into the ring to contest the US as a replacement global power. In pursuing its perceived national interests, China has somehow managed to upset every state in the region and a large number internationally. At least for the time being, its foreign policy looks dense and obtuse.

In the region of the South China Sea, geography, military power, economic strength and a centrally controlled narrative, all favour China. However, China’s reaction to the Philippines going to the International Court in 2013 was extremely vociferous. It embarked on an extraordinary global diplomatic effort to discredit the Philippine claim as well as the Tribunal itself. This was a complete diplomatic faux pas. The result of China’s activities was that it focused world attention on the judgement rather than diffuse it. This also belied the fact that China believed the Philippines did not have a case that would stand up to scrutiny. It was almost as if the Chinese knew that the ruling would go against them.

There were three strategic mistakes that China committed in the lead up to the judgement. One, it refused to participate in the arbitration process that it was signatory to, although the Tribunal did not need the participation of all parties to arrive at a decision. Two, it started building artificial islands in the disputed areas while the arbitration process was on-going. Three, it stated that it would not abide by the ruling even before a judgement was issued. These could form a list of what a nation ‘must not do’ when faced with strategic decisions that would have long term implications. The challenge now is to minimise the damage from the fallout of these actions. The fact remains that the ruling was both unanimous and overarching in its commentary. China’s choices going forward are stark.

China has two choices. The first is to continue on its current path of denial, defiantly resorting to a list of no factors—no participation, acceptance, recognition or enforcement. The PRC can also persist in asserting that the interpretation of the law is flawed and that the Tribunal was biased while continuing the activities that the court has condemned as illegal. The difficulty in adopting this choice is that by doing so China will almost immediately abrogate its moral and ethical right to state or stake a position in future international arbitrations of all kinds. China would be deemed to be contemptuous of international legal processes. No nation aspiring to global power status can afford to be in this state.

The second choice is what the international community hopes will be adopted by the Chinese leadership. It will involve stopping further provocative and destabilising activities. Subsequently, after a sufficient period of time has elapsed, China could gradually accept the court’s decision and reinitiate bilateral and multilateral negotiations. By doing so it will also demonstrate to the world that it has the necessary maturity to become a global power. It could then reinvigorate the process of regional cooperation, without the use of coercion. In any case China is unlikely to take any precipitous action before the G-20 meeting that it is hosting in Beijing is concluded in September. The maturity of the Chinese leadership will also be displayed if they manage to curtail the venomous statements regarding the ruling that has been coming out in the state-controlled media. This will indicate that China has shed its victim mentality. However, the second choice articulated above is a difficult one for the Chinese Government to adopt, especially with the rhetoric that has been drummed up recently. The unfortunate part is that it is impossible to predict the choice that China will make. The options are wide open.

The Role of the USA

The US policy towards South China Sea has been fairly consistent. While it insists that it will not support any one side in territorial disputes, it insists on ensuring respect for freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea. The US has called for peaceful resolution of disputes and the acceptance and implementation of multilateral and formal dispute resolution processes. In doing so it has also emphasised the need for all parties to respect International Law, including the UNCLOS. The US has made it clear that some aggressive moves by China, like the claim of enhanced air defence identification zone and the harassment of foreign, mainly US, ships and aircraft, are contrary to international norms and therefore not acceptable. The US stand on South China Sea has been vindicated by the Tribunal ruling.

Even though the judgement is in line with the US policy, it faces a slight awkwardness in acclaiming it. The US is not a signatory to UNCLOS. It asserts the right to freedom of navigation under the guise of the relevant rules having become part of the ‘customary’ international law. Further, some initiatives of the US-led opposition to counter China’s activities have been confrontational. The attempts to impose what the US calls a ‘rules-based order’ by drumming up support from regional allies and the use of coercive diplomacy is not conducive to the peaceful resolution of issues.

The court’s ruling has confronted the US with a Hobson’s choice. On the one hand it can call for China to adhere to and implement the decision. This might lead to a situation where the US will be forced to make a recalcitrant China, as it currently seems to be, comply with the judgement. It could lead to the use of military forces and the very real threat of conflict. However, if the US demand is not enforced in the face of a Chinese refusal to accede, it will be perceived as abandoning the region and will dilute its perceived commitment to International Law. A possible charge of hypocrisy in foreign policy looms large in these circumstances. On the other hand, not clearly articulating the need for China to respect the court’s ruling will almost immediately diminish the US ability to influence the regional nations. An overarching influence is necessary to ensure that a smaller nation does not embark on a path that aggravates an already tense situation. Now is definitely not the time to openly confront China, the consequences of doing so could be disastrous. If the US loses its influence in the region, it will also forfeit the small window of opportunity that it might have to provide China with a face-saving exit path.

The US has to be cognisant of another point of contention that has an indirect bearing on the emerging South China Sea situation. The US while not being a signatory to UNCLOS, uses the provisions of the same convention to justify its forward deployment of military forces. It also insists on exercising the freedom of navigation. It is obvious that China resents US military movements in its adjacent seas. A rhetorical question needs to be posed here—how comfortable would the US be if China deployed a carrier-group in international waters off the coast of California or New York, on a semi-permanent basis? The answer is obvious. As can be seen, the future depends a lot not only on Chinese actions, but also on how the US will proceed in attempting to diffuse one of the most volatile situations to confront the world in a long time.

The Future

Taking into account the sequence of events so far, as well as past and on-going statements of intent, it seems that the Tribunal’s verdict is not going to stop China from continuing its activities, at least in the short-term. The freedom of navigation patrols by the US and some of its allies will only be considered minor irritants. The Chinese refusal to scale down current activities will only reinforce the sense of coercion that regional nations already harbour. The urgent need now is to create a situation wherein China will be able to gradually climb down from the untenable position that it has created for itself. This would require nuanced diplomacy from regional nations, the US, and its allies like Australia, Japan and India. A lot now rides on the maturity of political leadership of these nations. This could alter the Chinese perception of victimisation and humiliation, although going by the reaction so far, such a change of heart seems unlikely.

There has also been a suggestion of a potential role for ASEAN in diffusing the situation. Its collective approach could have been a valuable tool in negotiating the way forward with China multilaterally. However, the forum is divided and not effective. On 25 July 2016, ASEAN adopted a joint communique in which the 12 July judgement was not even mentioned despite member nations being directly involved. Although ASEAN did have successes in the 1980s, it is not a dynamic body anymore. ASEAN can be discounted from being of any use in the current imbroglio. The world could be witnessing not the decline, but the disintegration of this grouping.

At the moment it is clear that regional nations must not start aggressive actions in the wake of the ruling. Any such action will only force China to dig-in and become inflexible, moving towards an even more untenable position. However, they must also strive to create a common multilateral approach to the negotiations that must take place in the near term. A collective approach will not only increase the bargaining power of the smaller nations, but also prevent China’s insistence on bilateral negotiations from becoming the norm. Even though China’s reactions and future plans cannot be fully predicted or understood, the judgement provides regional nations with an avenue to bring pressure on their large and powerful neighbour. The damage to China’s reputation in not complying with the unenforceable Tribunal ruling could be turned into a subtle tool of diplomacy for smaller nations.

Although restraint is being advocated, it is necessary to state that such restraint must not be at the cost of diluting the resolve, both regional and international, to ensure that International Law is upheld. Since there is no mechanism to enforce rulings made under International Law, consistent pressure must be applied to the recalcitrant participant. This can be done through insistent and vocal diplomatic advocacy. This is the only way to ensure that a global rules-based order prevails into the future.

Conclusion

The Tribunal’s judgement is a bold proclamation of the reach, power and utility of International Law. Like in most cases, this boldness is closely accompanied by inherent risks, especially since the Tribunal has no power to enforce its ruling. In fact, the legitimacy of the Tribunal itself may have been placed on line, since its continuing legitimacy is now dependent on China’s actions and the US reaction to them. Yes, there is a reputational cost involved for China in refusing to accept the judgement. It can also be stated that demonstrating complete disrespect for International Law is not conducive to becoming a truly great power. However, these become compelling arguments only if China considers them to be so. China can continue to ignore International Law while creating new paradigms on the ground.

If it is to be viewed as a responsible global power, there is no doubt that China needs to adopt visible and measured diplomatic efforts to calm tensions. The remarkable restraint shown by the Philippines Government is an opportunity for China to reciprocate. Of course, the Philippines’ restraint was also made necessary by the US not committing itself unilaterally to supporting any action. However, the administration of the new President Rodrigo Duterte has clearly emphasised their reliance on diplomacy and the restarting of the dialogue with China as a means to move ahead. This is a good start, since nationalistic jingoism will never achieve any long-lasting effects.

If China chooses to ignore the judgement, a probable course of action, it can no longer claim to be a law-abiding and responsible international citizen. It would also have jettisoned its claims to ‘peaceful’ rise to power. The already prevailing perception that it picks and chooses the international rules that it wants to honour, will become entrenched. Here a hypothetical question may provide some illumination on China’s attitude—if the Tribunal had ruled in favour of China, would it not have a sung a different song? The ground reality is that irrespective of the future actions initiated by China and the US, the judgement that has raised so much of dust has not resolved the South China Sea issue. In fact it has added a further layer to the complexity of the challenge.

China is determined to be a global power; that is the trajectory that it has chosen for itself. The Philippines, Vietnam and other regional neighbours therefore face the classic challenge that small nations have faced through the eternity of history. What can you do when a rising power, aspiring to greatness, brushes aside your claims to sovereignty?

China does not care on the Tribunal’s Judgement. If UNO closes their eyes on the China’s behavior it the high time that UNO can be closed down. China is the only adamant country around the world and it is expected that China will be the leader of the world and occupy the place of USA.

There are instances in the past where powerful countries have shown utter disregard and contempt for ICJ ruling. Weaker nation(s), can continue to be law abiding in the absence of a beter alternative. USA got away with it in the Nicaragua case during 1986, where it was required to pay reparations. It questioned the legitimacy of the court, the proceedings itself and never bothered. It also vetoed the implementation of the judgement five times. So much for international law enforcement!

I beg to differ. This is not going to affect China long term

First, this squabble is between 2 nations

2nd, tribunal ruling is one-sided and has no moral force

3rd the international community is for the most part not interested or involved

As reflected by ASEAN members response

The tribunal used strong words like violation and no historical rights. Which is overstepping its authority to do

So iIt even ruled Itu Aba a rock when everyone can see it is an island

It is obvious this is a manipulated tribunal to serve American and Japanese interest and therefore has no moral force The whole world watches and remain indifferent except for those nations bent on containing China

The ruckus will therefore fizzle out and the tribunal ruling ignored

For China to back down after taking a stand for so long, on their claims in South China Sea would not be acceptable to her in her backyard. Unless She has a face saving alternative. Cheque book diplomacy in an an endevour of calling it bi-lateral could be an option, especially with change in leadership in Philippines. Now that China is on the high table her behavior would be scrutinized minutely as it has global ramifications. China needs to be on moral high ground and a bully will be labeled like wise. China has to make the choice. The decision of UNCLOS would put a set back to her global ambitions by three- four years. (Only)