In-fighting In Iran – OpEd

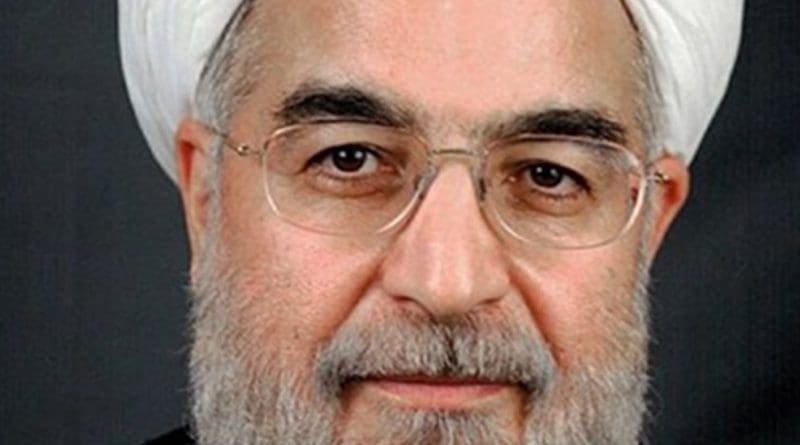

Iran’s élite are at loggerheads. Situation normal, one might say, except that the in-fighting is becoming more vicious by the day, exacerbated by the forthcoming elections. As Iran prepares for the vote, the power struggle between the hardliners on the one hand, and the moderates and reformists – the pro-Rouhanis – on the other, is intensifying.

Everything is not black and white in Iran’s body politic. There are two main political camps – Reformists and Principlists (conservative supporters of the Supreme Leader dedicated to protecting the ideological principles of the Islamic Revolution). The respected Speaker of the Iran’s parliament Ali Larijani, is nominally a Principlist, but he has supported Hassan Rouhani from the moment he became president. In fact, his support has been so strong that it has infuriated many hard-liners in parliament who have even accused Larijani – well-known for his anti-American views – of being a covert supporter of the US.

In particular, opponents of the nuclear deal were furious with the way Larijani, as Speaker, ushered through parliament’s ratification of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which marked the successful outcome of Iran’s nuclear negotiations with the P5+1 (US, UK, France. Russia, China and Germany). Whispers began to circulate that he was about to join the Reformists in the forthcoming parliamentary elections. In the event, on registration day Larijani announced that he was entering the fray as an independent.

Nevertheless the fact that moderate Principlist figures like Larijani strongly support the Rouhani administration has created internal tensions. Asadollah Badamchian, a respected member of the group, recently said, “We are working hard to unify the Principlist movement…for the parliamentary elections.” They are inviting prominent politicians such as the Supreme Leader’s foreign policy adviser Ali Akbar Velayati, Tehran mayor Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Ali Larijani himself to form an advisory council tasked with bringing unity to the movement. But with Larijani standing as an independent, some political observers believe that after the elections the Reform Movement might approach him to join them, or at least to enter into some form of cooperation, with the aim of continuing their support for Rouhani’s liberalizing programme.

Tensions have existed in the top echelons of Iran’s regime for decades, but Rouhani’s victory in the 2013 presidential election have given them a sharper edge. As he began to implement the change in approach to the West that had obviously been agreed well in advance with the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, hardliners in the top echelons pitched a rearguard action against every phase of the nuclear deal as it was hammered out.

The end of international sanctions, far from being greeted on all sides, is only intensifying the in-fighting among the faction-ridden élite. Fundamentalists not only believe the price demanded was too high in terms of the dismantling of Iran’s nuclear capabilities, but are determined that Iran will renege on the conditions whenever it suits.

Since taking over as Supreme Leader in 1989, Khamenei has always made sure that no individual or group, including among his own hard-line allies, gains enough power to challenge his authority. So Rouhani cannot count on his political support, either in respect of the nuclear deal, or on domestic policy, before the elections in late-February 2016 for the Majlis, Iran’s parliament.

According to the Islamic Republic’s constitution the election of the Majlis must be monitored by the body known as the Guardian Council, a hard-line group controlled by Khamenei. The world gets to hear very little about the long-running dispute between senior hard-liners in the administration and Rouhani and his supporters about how much power the Guardian Council has, or should have, in vetting electoral candidates.

Based on past practice, the Guardian Council could engage in mass disqualifications of candidates and eliminate entire political groups. On January 16, 2016 Iranian television carried a statement from the Guardian Council to the effect that more than half of the record number of 12,000 candidates to register in the forthcoming parliamentary elections were unqualified to run. Many of the disqualified candidates came from the Reformist and moderate camps, groups that would have been allied with the president in creating a more open political climate in the country.

During a press conference the next day Rouhani said he would use all his powers to address the disqualifications, and hoped the Supreme Leader’s comments about having lively elections would be fulfilled. On January 18, Elham Aminzadeh, legal deputy to the president, announced that Rouhani was “negotiating with the Guardian Council over the disqualification of candidates.” If a mistake had been made, she said, they would seek to restore a candidate’s registration.

It appeared that parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani was also in talks with the Guardian Council over the disqualifications. Mohammad Reza Tabesh, a member of parliament, said that Larijani was seeking to create a work group with members of the Guardian Council so that candidates who were disqualified could have a special hearing to present their complaints in person.

“Rouhani has gained even more popularity compared to 2013 because of his nuclear success,” said a senior Iranian official. “People know that Rouhani’s policy ended Iran’s isolation and their economic hardship. He is their hero.”

Rouhani’s increasing popularity might not be to the Supreme Leader’s liking. Khamenei depends less on popular acclaim than on the support of the hard-line element within Iran’s internal power structure. To retain it he might feel obliged to cut his president down to size. This is why political analysts within Iran examine the entrails of every move that Khamenei makes.

For example, his unshakeable rooted opposition to the US – the “Great Satan” – cannot but be music to the ears of his fundamentalist supporters. In a succession of speeches Khamenei has made it very clear that the nuclear deal (Iran’s “victory” he dubs it) affects Iran’s basic enmity with the US not one jot. “I reiterate the need to be vigilant about the deceit and treachery of arrogant countries, especially the United States,” he said, on January 19, 2016.

He believes that the US will try to exploit the forthcoming elections for its own ends. In streetwise belligerent mood, he told a meeting of prayer leaders early in January: “Americans have set their eyes covetously on elections, but the great and vigilant nation of Iran will act contrary to the enemies’ will, whether it be in elections or on other issues, and as before will punch them in the mouth.”

The truth is that however popular Rouhani might have become, without Khamenei’s blessing his supporters could get nowhere in the 2016 elections. So the big question is how much leeway can the Supreme Leader allow Rouhani and his supporters, and still retain the balance of power in the body politic that he regards as essential to his own survival?

In short, will Khamenei bow to popular pressure and give his blessing to Rouhani’s bid to fulfil his liberalising pledges to the electorate, or will the internal fundamentalist pressures prove too strong?