Japan’s Bigger Defense Budget: Getting To Effective Deterrence – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Felix K. Chang*

(FPRI) — “We have to prepare for realistic possibilities to protect our people,” counseled Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida during a political debate in October 2021. To do so, he argued Japan must not only strengthen its Self-Defense Forces (SDF), as its military is called, but also give the SDF the ability to strike military facilities on its potential adversaries’ soil as a way to deter them, a controversial strategy for the pacifist-leaning country. A little over a year later, in December 2022, Kishida’s cabinet took a major step towards turning that concept into a reality when it approved a huge 26.3 percent year-over-year increase in Japan’s 2023 defense budget.

The new budget made it clear that Kishida intended to follow through on his earlier pledge to double Japan’s defense budget from about one percent of Japan’s gross domestic product—a level that it has maintained for the last six decades—to two percent by fiscal year 2027. But despite Japan’s substantially bigger 2023 defense budget, which will total some 6.8 trillion yen (or $51.4 billion), its near-exclusive focus on new weapon systems might not prove entirely effective at creating the deterrent effect that Kishida seeks. Rather, to produce that effect, Japan may be better off building a military that is not only better equipped, but also better manned.

A Dangerous Neighborhood

No doubt, Tokyo was driven to boost its defense budget by its concerns over the potential dangers posed by China, North Korea, and Russia. That much was clear from Japan’s latest national security strategy, which was released a week before the new defense budget was approved. China’s repeated incursions into the air and sea spaces around the Japanese-claimed Senkaku (called Diaoyu by China) Islands, the establishment of a Chinese air defense identification zone over much of the East China Sea, and the frequent presence of Chinese military forces near Japan had clearly put Tokyo on edge. Then Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine prompted worries that China could be emboldened to attack Taiwan and perhaps draw Japan into the conflict. Surely, Japanese officials nervously watched China as it lobbed several ballistic missiles into the waters near Taiwan (five of which fell into Japan’s exclusive economic zone) in August 2022.

Meanwhile, North Korea and Russia reminded Tokyo that they warranted continued Japanese vigilance, too. In 2022, North Korea launched thirty-seven ballistic missiles into the waters near Japan, more than in any other year. And, as if to herald the following year, North Korea launched one more in the early hours of New Year’s Day. At the same time, Russia’s increased cooperation with China and invasion of Ukraine revived Japanese concern over its northern border, particularly over the four islands between Japan’s home island of Hokkaidō and Russia’s Kuril Islands which have been disputed between Tokyo and Moscow since the end of World War II.

Facing simultaneous security challenges from the south (China), west (North Korea), and north (Russia), Tokyo could no longer focus its resources on one challenge at a time. It had to deal with all of them. As a result, defense policy became a key issue during the Japanese Diet’s lower house election in 2021. Indeed, a record number of Japanese today feel the need to bolster their country’s long-stagnant defense capabilities, the basic composition of which has remained nearly unchanged since the 1980s.

New Combat Capabilities

By far the most discussed aspect of Kishida’s defense budget was its provision for long-range land-attack missiles to establish Japan’s “counterstrike capability.” Tokyo recently revealed that it would fill that role with American RGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missiles. Its selection had been somewhat expected, given that Tokyo was reportedly in late-stage negotiations with the Tomahawk’s manufacturer in October 2022. What was more surprising was the number of missiles that Japan might buy. Considering that Japan’s 2023 defense budget has allocated $1.6 billion to buy the missiles and that the cost of each missile is about $2 million, Tokyo could purchase as many as 800 missiles.

Depending on the variants of the Tomahawk that Japan purchases, the SDF will be able to launch the missiles from shore batteries, surface warships, submarines, or aircraft. And, with a range of between 550 and 2,500 km, again depending on the variants, the missiles would enable Japan to strike military facilities across northern China, North Korea, and the Russian Far East. However, as the missiles travel at subsonic velocities, they could be vulnerable to modern missile defenses. Thus, a reason why Japan may have chosen to purchase so many missiles is to ensure that even if a good percentage of them are shot down, it would still have enough to deliver an effective “counterstrike” and, thus, ensure a degree of deterrence.

In any case, the Tomahawk missiles seem destined to be an interim solution. Tokyo has already planned to develop new surface-to-surface missiles that will have ranges of over 2,000 km and incorporate hypersonic technologies. Indeed, much of the rest of Kishida’s defense budget will fund additional munitions and a variety of military modernization programs. Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) can look forward to sixteen more American F-35 joint strike fighters, half of which will be embarked on Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force’s (MSDF) two converted light aircraft carriers. Resources will also go into anti-missile defenses, cyber security, unmanned aerial vehicles, and a research-and-development partnership with Italy and the United Kingdom to create a next-generation fighter jet.

Too Lean to Be Mean?

However, conspicuously missing from Kishida’s defense budget was funding for a larger force structure. Since 1980, the SDF’s authorized strength has remained steady at slightly under 250,000 personnel. Today, it stands at just 247,000. If Japan is to meet the simultaneous challenges posed by its potential adversaries and credibly deter them, it will need a larger SDF. One that is not only more lethal, but also more resilient—able to conduct sustained combat operations and handle a larger number and wider variety of scenarios. That will require more personnel.

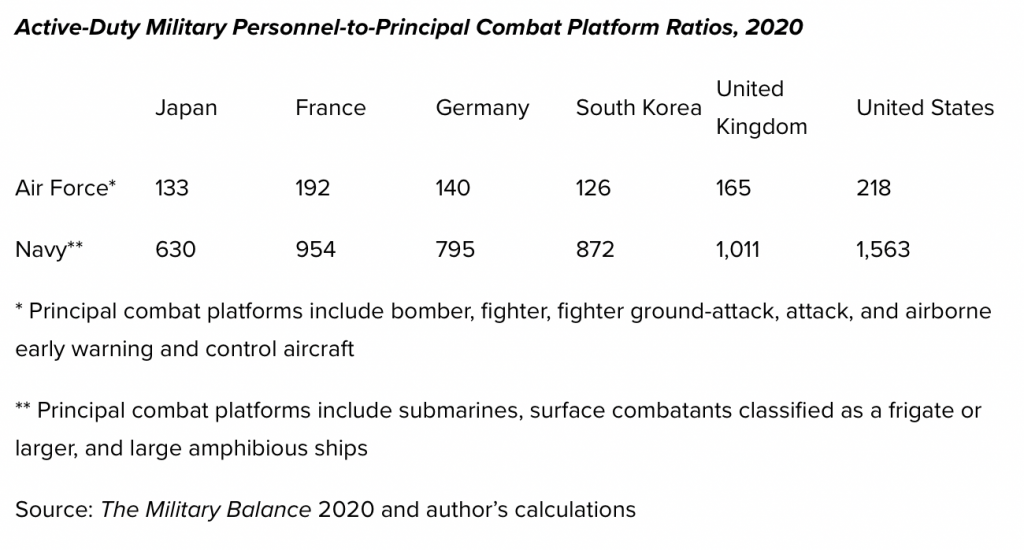

Japan’s current armed forces run lean. That can be seen in their low active-duty military personnel-to-principal combat platform ratios, which reflect the number of personnel that a service needs to field its combat power. The ratios are especially useful when evaluating combat platform-centric services like air forces and navies. At present, Japan’s ASDF and MSDF have lower personnel-to-combat platform ratios than almost all the other air forces and navies of the West’s top defense spenders, with the exception of those of the United States, whose air force and navy are designed to project power globally.

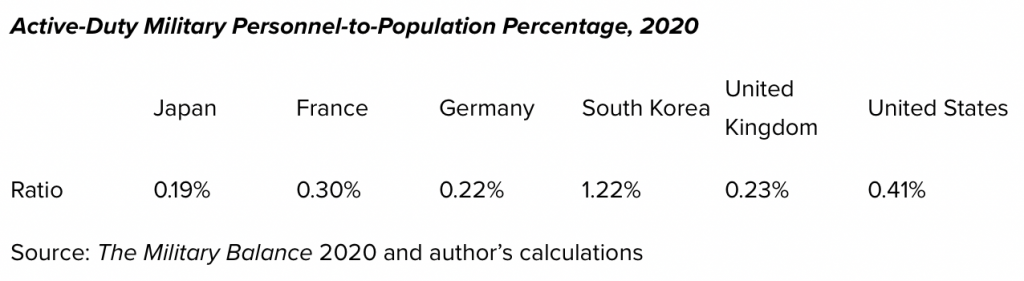

Japan could field bigger military forces. Higher salaries and benefits would help the SDF fill current recruiting shortfalls. And despite its shrinking population, Japan’s active-duty military personnel as a percentage of its total population trail those of other major Western countries. Should Japan match the percentages of Germany or the United Kingdom, it could boost the SDF by as many as 25,000 more personnel. They could not only beef up the SDF’s frontline forces, but also bolster its sustainment, repair, and regenerative capacities, making it more resilient.

More Resilience Needed

However, convincing Japanese legislators to increase the ceiling for military personnel will be a high hurdle. Already, they are concerned about how to pay for the recently-approved defense budget increase. Hence, for the immediate future, Tokyo is more likely to economize on military personnel and operate the SDF within its existing force structure. To bolster the ASDF and MSDF—arguably the most important services for a counterstrike strategy—Japan’s Ministry of Defense could shift personnel billets from its Ground Self-Defense Force to supplement them. It may also try to economize with technology, such as acquiring warships with greater automation that can be operated with smaller crews. But such economizing comes with trade-offs. In the case of smaller warship crews, the trade-off comes in terms of ship survivability in combat.

From a budgetary perspective, the Japanese government’s preference to operate such a lean military may be admirable. But from a military perspective, it could also be perilous. To be effective in combat, a military must be resilient. Its frontline forces must have enough logistical support to keep them properly supplied and sufficient repair and regenerative capacities to keep them at fighting strength, even in the face of losses. That ultimately necessitates more personnel, a lesson that could be learned from Japanese history. It is replete with examples of overly lean forces being sent into battle and suffering either excessive casualties or avoidable reverses as a result.

Having a lean military might have been adequate for a time when future wars were thought to be short and limited. That may not always the case, as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine demonstrates. Wars can unexpectedly evolve into lengthy and escalatory affairs. Certainly, once the SDF begins to receive its new weapon systems, it will have more combat power at its disposal and can provide Japanese leaders with new diplomatic and military options. But if Japan is to credibly deter its potential adversaries, it must convince them that it can go toe-to-toe with them. And that demands more than just firepower; it requires resilience.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

*About the author: Felix K. Chang is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He is also the Chief Operating Officer of DecisionQ, a predictive analytics company, and an assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

Source: This article was published by FPRI