Testing The Strength Of India-Japan Relations – Analysis

By IPCS

By Dr Sandip Kumar Mishra *

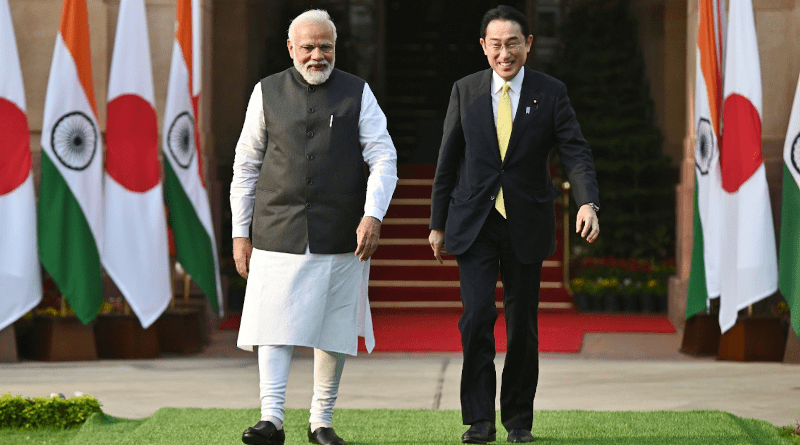

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited India in March this year. In a joint press conference with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Kishida raised the issue of Russia’s “aggression” with Ukraine. The difference between the Japanese and Indian positions is being reported as a “gap” on a critical contemporary global issue. Some commentators have gone to the extent of questioning the depth of the bilateral relationship on this basis. Before jumping to such hasty conclusions, however, it is important to understand the various layers of the India-Japan relationship. Where do they converge, where do they diverge, and is there room for both to co-exist?

Convergences

Kishida’s recent visit led to a joint statement titled “Partnership for a Peaceful, stable and Prosperous Post-COVID World.” In an Indian Express op-ed published to coincide with the trip, Kishida evoked “universal values such as freedom, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law” shared by the two “Special Strategic and Global Partners.” Incidentally, India and Japan also mark 70 years of diplomatic relations this year.

Bilateral ties have been very positive over the past seven decades, with the singular exception of a period of stress following the 1998 Indian nuclear tests. Both countries recognise their complementarities, and have strong economic, strategic, historical, and cultural connections. India is one of the international beneficiaries of Japanese investments in human and economic development projects. Both countries have gradually moved to articulate their common security concerns. Their defence and security ties have been strengthened, and they now host annual summit and 2+2 meetings.

India and Japan share several commonalities at the regional and global levels. They are concerned by the rise of an ‘assertive China’ while also engaging it economically in a very substantial way. Even with China being both India and Japan’s number one trading partner, its potential dominance in Asia might be the most important aspect of the New Delhi-Tokyo bilateral. Still, even if China’s role and responsibility for the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as its aggressive regional actions is the subject of heated debate, including in India and Japan, both New Delhi and Tokyo’s bilateral trade with Beijing has been stable. In fact, the figures have gone up.

Further, India and Japan are part of the Quad with the US and Australia. Although India doesn’t have a formal security alliance with the US, the ties have deepened substantially in recent years. India and Japan are also cooperating closely through their respective Indo-Pacific strategies. Japan became a permanent member of the Malabar naval exercise in 2015, at which point it turned into a trilateral format. New Delhi and Tokyo are also engaged with ASEAN countries and consider the grouping’s role central in any future political, economic, and regional security architecture.

Divergences

There are also some important gaps between the two countries’ foreign policy approaches. These are the products of historical and structural factors. The first gap is the kind and extent of autonomy both countries seek from the US. Whereas Japan has historically aligned its security interests with the US—an ally since 1953—India holds its non-aligned years as a point-of-reference. On nuclear and missile issues and the environment, Japan takes up positions that are similar to the US’. India, on the other hand, tries to articulate positions based on its own realities. Gaps in perspectives have also appeared on North Korea, Iran, and most recently, Ukraine.

India has enjoyed a long and time-tested relationship with the former USSR and later, Russia. During the Cold War, India received consequential assistance from the USSR. The country’s defence sector is closely related to/dependent on Russia. New Delhi’s approach towards Moscow in the Ukraine crisis is thus informed by historical and structural foundations. India and Japan being able to give space to their respective positions when views diverge is testament to the understanding implicit in the relationship. They are unlikely to allow differences of opinion to come in the way of expanding cooperation on areas of convergence.

A closer analysis thus reveals that any gap in the Indian and Japanese positions on Ukraine—or any other issue—doesn’t indicate a weakening of the relationship. On the contrary, it is suggestive of maturity.

*Dr Sandip Kumar Mishra is Associate Professor, Centre for East Asian studies, SIS, JNU, & Distinguished Fellow, IPCS.