Tafteesh-E-Ibadatgah: A Comparative Analysis Of Temples

Temples have been the most recognised avenues for long lasting tangible and visible experience of the actualisation of people’s’ religious faith and belief. Temples have not been the passive avenues, performing the said function. Since ancient times, they have been centres of public life and have played a crucial role in organising and shaping the social, political and economic life. However, there has been a qualitative change in the nature of functions that are associated with temple culture.

Taking this functional differentiation as the base of its comparative analysis, this paper presumes two kinds of temples as its category of analysis- one, which are largely centred around the function of religious worship and the other, whose core function is not religious worship but which nevertheless derives the kind of legitimacy, it has from being associated with religion. This paper seeks to test this hypothesis to understand the nature of the temple culture as it has developed into in the contemporary times.

Introduction

Religion as a set of belief systems and a social culture has played an important role in the lives of human beings since time immemorial. In that sense, religious establishments , even though they might be of younger origins can be said to be dealing with something as old as history itself. Temples, since their origins have shaped the socio-economic and political organisation of the society in significant ways. It is for this reason that the temples have been objects of great interest to social scientists. (Nath: 2010)

However the category of temples is also not a homogenous category. Even a cursory glance at the temples of modern times suggests a great deal of diversity in terms of its scale, functions, reach, the manner in which its economy operates etc. Of all these variations, we found the functional differentiation to be the most appropriate parameter on the basis of which a comparative analysis is possible.

In making use of a functional approach, we see the temple complex as a social system which is composed of various structures performing multiple functions. In this sense, we shall be looking at the physical, cultural and the psychological components of the temple that interact with one another to give rise to the social system that the temple represents.

This paper arrives at three categories of temples for the purpose of comparison – A, B, and C. At certain places, the paper refers to these categories as fused, prismatic and diffracted. The nomenclature for these terms is derived from Peter Riggs ecological approach to public administration, where he used these terms for different types of administrative systems. However this borrowing of nomenclature does not suggest the wholesale import of the idea that Riggs put forth. The use of terms merely suggests the existence of specialised structures for the diverse structures that the temples are observed to be developing. (Arora: 2003)

The religious and extra religious functions performed by the temples forms the core distinction of this paper. Further we also explore the diversification of the activities that a temple has been a hub of, and whether this diversification points towards some linear progression.

Greater differentiation is not to be confused with any devolution or decentralisation. A characteristic feature of the most modern institutions, and indeed modernisation itself is that the greater diffraction of functions often emanates from and is regulated by a central authority with monopoly over decision making. One of the objectives of this paper shall be to test the correlation between functional expansion and the centralisation of authority.

Research Methodology

This paper takes the two categories of temples, as its starting point on the basis of their different functional cores – of religious and extra religious functions. The functionalist theory, and the concepts of modernisation and anti production forms the theoretical base of this paper, which then uses qualitative and quantitative methods of enquiry in the pursuit.

The temples that this paper surveys consist of the some temples in New Delhi- Akshardham, ISKCON (in East of Kailash, New Delhi) and Chhatarpur temple along with a number of local neighbourhood temples. In the attempt to be accommodative of the complexity that reality presents, this paper refrains from using a multi choice questionnaire as its methodology. Instead, the questionnaire framed for the purpose just suggests the templates on the basis of which the context sensitive responses of the respondents may be brought within the purview of the analysis. The basic questionnaire is attached along. The respondents approached may be categorized into these groups: visitors, priests, employees, nearby stall-keepers and tourists (separate from local visitors). The total sample size of the survey is 30.

All the questions were directed towards testing the organization of various activities that take place and functioning of the temple, the variety of options namely the extra religious activities that happen and the scale and quality of it, the appointment and other recruitment decisions and the reach of the temple as a historical and/or religious and social entity.

On the other hand our qualitative approach consisted of observing the real, tangible affairs and objects by being one of the many visitors in the temple all of which were directed towards the same objective as that of questionnaire. While majorly the quantitative approach is the basis of our research, the observations add to our analysis and understanding of the concerned affair.

Features of Temple Economy

Elements of Priests’ lives

Frequency of people’s association in temples

The subjects were interviewed on the basis of certain criteria. Firstly the types of temples to be studied were selected as local temples, industrial complex-cum-temples which were Akshardham temple and the ISKCON temple and lastly, the Chhatarpur temple which represents characteristics of both of these. Next, the groups to be interviewed were identified. So the target groups for the interview were the devotees, the priests, tourists and visitors, and finally the employees in the temple, that is, those who support the temple economy. The target groups were interviewed keeping in mind the fact how they experienced their relation to the temple in different ways and how they felt the temples interacted with them too.

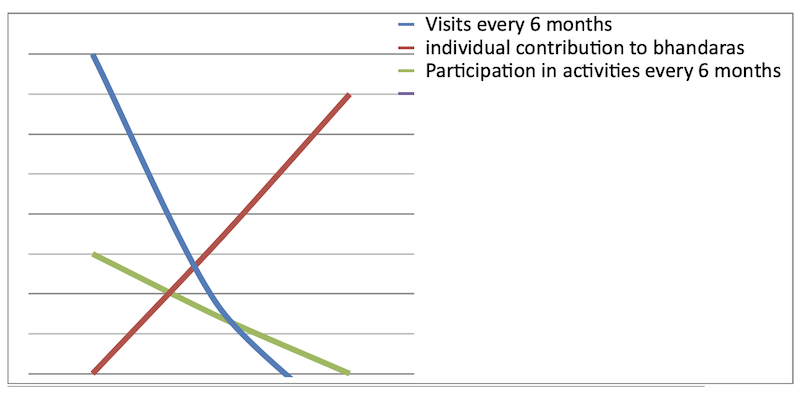

Taking devotees first, it was found that their interaction with the temple was affected by the environs they were in. In local temples it was found that there were close connections to the temple as the devotees went there for their daily prayers and were more intimately involved in its activities like celebration of important life events etc. Moving on to Chhatarpur, it is seen that the devotees were somewhat less focussed on establishing strong ties to the temple than to worship the deity- something that was palpable in their contributions to temple funds and celebrating life events. At Akshardham and ISKCON, the focus moved almost entirely to worship and enjoyment of the amenities that the temples boasted about. Here it was found that the subjects were more isolated in terms of their proximity with the temple environs as they hardly looked upon them as places of celebrating life events and local festivities.

The tourists and visitors showed a palpable interest in going through the Chhatarpur temple and Akshardham and ISKCON as places of mere tourist interest with a remarkably less interest in the religious aspects of the places. The local temples however brought about quite closer interactions with visitors and tourists- just as they did with the devotees.

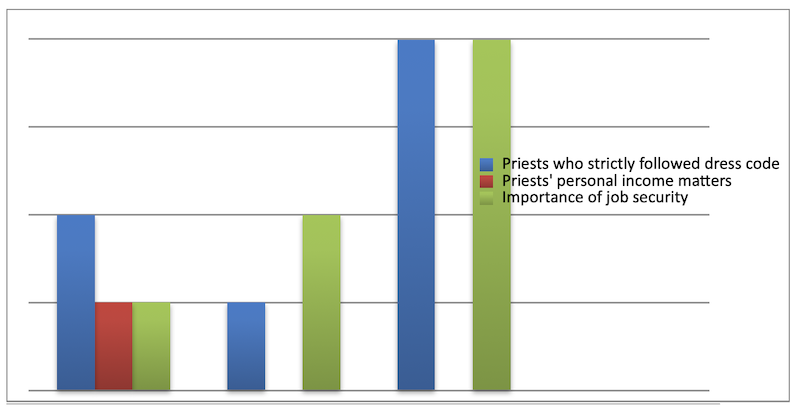

The priests in the local temples are somewhat informal about their appointment to positions of authority and were quite open about the procedure too. The Chhatarpur temple however was noticeable for there it was relatively difficult to get to know about the administerial procedures-something that was absent in the Akshardham temple and the ISKCON temple. Also it was uniformly observed that in the local as well as the Chhatarpur temple, the priests were engaged in their profession due to economic reasons whereas in the Akshardham temple and ISKCON the job was mostly voluntary with motivation being devotional rather than economic.

The employees and supporting staff of the local temples were mostly the panḍit and his close family itself while in the other two types of temples people were properly employed to handle the larger responsibilities that these temples demanded. The Chhatarpur temple attracted migratory people as their staff and also they were concerned with merely economic reasons to be attached to the temple- something palpable in their multiple employments outside the temple. The Akshardham temple and ISKCON temple however had employees who worked with job security- reflected in their motivation to work out of devotion rather than finances.

Observations

| Temple C Akshardham and ISKCON | Temple B Chhatarpur Temple | Temple A Local neighbourhood temples | |

| 1. Established very recently 2. established as branches of an existing temple. 3. An organisation in place to oversee the network of temples at the global level. | 1. Cult of a saint 2. Geographical and functional expansion since then 3. Organisation to manage | 1. Established by a group/community 2. Sole purpose: religion 3. Managed by trust- formally well defined structure; elections held | Origin and further development |

| 1. have an international presence and reach 2. A part of a network of similar temples | 1. Multiple temples within the complex 2. Presently stand alone, but seeking a wider presence | 1. Stand alone temples 2. In case of government funding , it may be linked to other similar temples in terms of personnel, rules etc. | The network of temples |

| 1. Grand architecture 2. sophisticated architecture 3. overtly religious symbols not present , given the broad appeal that it aims for. | 1. Attempt to emulate the grandeur of the well known temple architecture 2.The finesse missing 3. Remarkable presence of the cult symbols. | 1. residential buildings- shows the patrimonial character of the temples 2. Internal mirror decoration common | Architecture |

| 1. Entry mostly free 2. Charges -Entry within certain parts of the temple -Charges standardised, categorised and universalised 4.Donations | 1. No mandatory charges for entry 2. donation -major source 3. Charges – for specialised rituals -Renting mandir space -Extra religious activities within the complex | 1. no mandatory entry, shoe keeping charges 2. Charges for – specialised rituals – Renting complex space 3. Donation-said to a major source 4.government funding in some cases | Revenue |

| 1. However,despite the presence of volunteers, a large permanent staff are a must for taking care of the diverse range of services provided | 1. Functional differentiation 3. Pandit+permanent salaried staff 4. Devotees making religious contribution(Sewa) | 1. Ad Hocism 2. 1-5 priests 3. Few people hired for the intensive cleanliness, repair of the temple etc. as and when deemed to be necessary | Staff Structure |

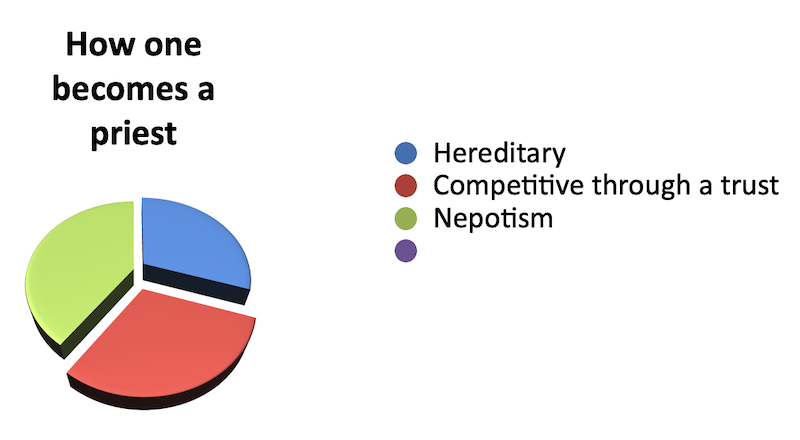

| !. A curious case was running into a Russian priest at ISKCON temple who when asked about his presence said “Krishna Radha” | 1. Advertisements sent 2. Basis: education in priesthood, experience , merit etc. 3. contact with an insider may be crucial (alternative interviews) | 1. Basis: said to be merit, experience 2. Influence of kins crucial 3. Contradicting instances-a very young pandit | Selection of Staff |

| 1. Priestly duties within the temple 2. General security in the inner sanctum | 1. priestly duties within the te 2. caretaking of the temple 3.Rituals in people’s’ homes, for additional income | Role of Priests | |

| 9:30 am to 8:00 pm | 1. 6:00 am to 10:00 pm | 1. Around 6-12 and 4-10 2. 12- 4 | Timings of the temple |

| 1. Metro and Bus stop in the name of the temple 2. Feeder transportation plying to and from the temple | 1. Shops selling offerings 2. Food stalls, shops 3. Metro, bus stops and feeder transport services in the name of the temple 4. Very few beggars | 1. Few shops selling religious offerings | The temples contribution in the larger economy of the region |

| 1.Religion as the legitimising factor is heavily commercialised 2.Known for its exhibition, theatre,tourist entertainment provisions. | 1. A range of socio- religious activities, not confined to worships 2.Accessibility to the idols of deities 3.Online information on religious celebrations | 1. Core function: religion 2. A link between people and religious traditions, occasions maintained | Element of Religiosity – Religiosity is the actualization of religious beliefs of people. (Temples in general are believed to provide the most tangible experience and view of religiosity) |

| 1. Has originally come up around the cult of a saint 2. However, in order to widen the appeal of the temple beyond the members and followers of that particular temple, the temples also accommodates other deities | 1. Regional deities as well, but given a mainstream appearance 2. The speculated reason- Delhi being a conglomeration of diverse people from diverse faiths and regions require their faiths to be represented in the temples. However the cosmopolitan nature of the city also requires a certain mainstreaming of these regional gods and goddesses | 1. Mainstream deities. 2. Specific faith of the region creates space for regional deities as well. Like Jhulelal in a Sindhi locality | Deity |

| 1. Immense security checking – metal detectors, frisking , vehicles searched 2. Restrictions in what can be allowed inside | 1.Nominal Security Checking 2. CCTVs in plenty 3. Voluntarism relied on a great deal | 1. No security checking at any point 2. Voluntarism a. Placards specifying guidelines 3. CCTV cameras deployed- self surveillance | Security Structure Security here implies not just the the protection of life and property from destructive forces , but also ensuring the maintenance of the temple |

| 1. The provision of theatre, boat ride, exhibition within the temples 2. Demarcation between religious and extra religious enterprises less clear | 1.Vast range of religious and social services – accommodation, space for social celebrations, hotel, educational institutions, medical and diagnostic centre, Vocational training centre etc. 2.Major element in the geographic expansion 3. All such structures have their separate premises, even though in totality they constitute the temple complex. | 1. Extra religious activities added- accommodation, space for celebrations 2. Major source of revenue to the temple 3. But still secondary to the primary religious function | Extra Religious Activities |

| 1. Some temples might enforce a dress code for the visitors as well 2. Akshardham : elaborate dress guidelines specified to preserve the sanctity of temple | 1. Dress code of all priests is exactly the same , including the shoes. 2. No restriction specified for the attire of the visitors as such. | 1.No dress code specified unless objected to by local worshippers 2. Visitors still exercise self surveillance in the attire 3. Dress code for priests-kurta- dhoti is the standard attire, most commonly in saffron, or yellow colours. but some variance in clothing observed | Dress Code |

Discussion

The various temples that we surveyed in the survey, exhibit a range of features which is not always possible for one to give a clear cut and coherent categorisation of the temples as a whole. However on the basis of the broad comparison of the functions between the features, this paper puts forth a broad categorisation of the temples in three categories.

Category A of temples is functionally centred around as places of worship. A range of diverse functions may be added later to the temple, like almost all temples have now developed as an avenue for social celebrations. However, the religious function it performs still is predominant in these categories. The distance between the deity and the devotees in these temples is minimal, due to reasons of not so much focus on enforcing security. However, the sense it gives is of greater accessibility to the ‘deity’. The information regarding the auspicious occasions is provided to the devotees, and some events organised to celebrate the same or mark their significance. For instance, one local temple surveyed organises a ‘katha’ every purnima. Through these regular events, the local temples manage to keep their role primarily as religious avenues intact.

Even in the extra religious activities that these temples have been the hub of recently, the religious sentiments of people remain a major consideration behind the decision of the organisers in holding these celebrations in the temple. The primarily religious role of the temple is evident from the manner in which the extra religious elements are incorporated into the temple. Instead of including new elements within the temple to perform the newly added functions, already existing structures are used to provide the newly added functions as well.For instance, the premises of the temple may be used for celebrations etc. without the addition of any new space for the same.

The functional fusing is also evident in the patrimonial character of the temple. In the sense that the pandit is seen to perform multiple functions or even all major functions in and related to the temple. Thus patrimonial here means that the entire temple complex seems to be the personal household of the priest, regardless of his ownership of the temple.

The temple for a whole range of its existence, including the donation ,the dress code, the maintenance and security of the temple etc. relies on the voluntary cooperation of the visitors to a great deal. This even though not having a legal backing to it, is a powerful force within itself. Here, Talcott Parsons in his’ Voluntaristic theory of action’ gives us a reasonable explanation for this cooperative behaviour of the people, despite there being no legal provision making such a requirement. He conceptualises action as being composed of three “interpenetrating action systems” the cultural, the social and the personality. In the case of the temple system, it is easy to see how individuals’ behaviour is shaped by their religious beliefs and

This voluntarism nevertheless works in A category of the temples. This is because the devotees’ actions in a temple are determined by their orientation, their motives and values, both of which are conditioned by their religious beliefs in this case. In this case, even though donations are not mandatory in a temple, most people tend to contribute something because of their deep personal association to the religion and the construction of normativity around the act.

Category C of temples that we looked at was the temples whose functions are not centred around their function as places of worship. The temples that we placed in this category are Akshardham and to a lesser extent, ISKCON. The extra religious components in this category are far more prominent. The responses of the visitors suggest that it is for these entertainment activities rather than worship that they visit the site for. The temple is by and large a tourist spot, an enterprise that aims towards producing the most satisfactory religious experience for its customers.. The extra religious activities cannot afford to be very far from the religious aspect of the temple, they need to have them around to gain legitimacy from their backing by the religious activities of the temple.

In this category a centralisation of authority is seen, which regulates each and every aspect of the temple culture. This regulation does not rely on the self- surveillance by the visitors according to the prescribed norms of the society and has been given a legal dimension. One reason for this could be the capability of such temples to ensure the implementation of the desirable conduct within the temple, which further indicates towards the resources it controls and is successful in extracting from the visitors.

This significant factor is by and large absent in the previous categories (A and B) of the temple. Another could also be that the shared norms that the A and B categories rely on for the voluntary cooperation of the devotees can not be presumed in the C category temples. A significant chunk of the population that visits the temple comes from areas across the world that have very different socio-cultural norms. Further, the majority of the population visit the temple as tourists and not as devotees, and hence may not be in a requisite religious state to adhere to the religious requirements of the temple culture. Both these factors make it necessary and possible for the temple authorities to formulate and enforce certain mandatory guidelines.

Among all these guidelines, some are of a rational and secular character.Like that which are designed to ensure the security of the complex. However, some guidelines are those which exist to provide sanctity to the tradition that the temple is said to be based on. One such example is the dress code that is prescribed for the visitors in the C category temples.However, in our survey we found that not all temples can be classified into these two categories of temples that this paper initially presumes.

A temple like Chattarpur (category B) is functionally diverse and has diffracted structures for the performance of these functions. However, the temple premises at least show a dominance of the religious aspect. Further, there is a difference even in the extra religious functions it performs, when compared to A and C category temples. Such functions are decidedly of socio-religious nature, and not of the tourist entertainment kind provided by the C category temples. This might be the reason why even though such extra religious structures are established separate to the temple, because the nature of their functions does not place a requirement on them to gain their legitimacy from the proximity to religious sanctums of the complex.

Also even though there has been a tendency within the temple to move towards the adoption of rationality in the ‘modern’ certain areas, a great deal of formalism i.e. discrepancy between the formally prescribed norms and effectively practiced reality may be observed. This formalism is evident in the manner in which the staff committee is selected. There is a declared “donation structure” in Chattarpur Temple in the sense that there is a fixed rate for a particular kind of activity that one wants to organize.

However, contrary to what the proponents of structural functionalism are prone to proposing, it does not automatically follow that the temples wish to completely modernise along lines that are completely rational and legal in character. However what also needs to be pointed out is that the temple and its members are quite comfortable in adhering to many of its non-modern aspects like the voluntary (and not enforced) religious service to the temple done by the devotees. The temples in the first and the second category despite their adherence to the more traditional modes of operation do show an inclination towards developing norms and rules of a rational legal character.

It is interesting to note that the assumption of a linear pattern in the development of temples emerged flawed. It comes from a psychoanalytic reading of the trajectory of modernity and its effects. In the case of temples the term “anti production” employed by Deleuze and Guattari in their seminal work Anti Oedipus is instrumental. This expression symbolises the inherent temporality in the evolution of any entity means that temples, instead of unquestioningly progressing into the appendages of modernity, retain that gleam of past and the alternative. This synthesis always recalls the elements of thesis and antithesis. Thus, it would be premature to pronounce a strictly teleological judgement on the conceptualisation of temples.

Conclusion

The research paper began with the categories of two temples based on the level of functional diversity and diffraction observed between the two. However, even in the limited empirical research that this paper was able to undertake, the reality proved to be too complex for these two categories. The features of these temples are too diverse to be explained by these two categories. Thus, the three type model that this provided seemed more conducive for the purpose of comparison, even though this model evidently has its shortcomings in explaining or even describing all the features of the temples we surveyed. This problem of discounting of details and generalisation is however inherent in the very act of theorizing itself.

Akanksha and Monika, research scholars from Jawaharlal Nehru University, contributed significantly to this article

BIBLIOGRAPHY

www.chhararpurmandir.org

Nath, K. (2010). Economics of TempleCulture: A Case Study of Tarakeshwar. Retrieved December 2021, from shodhganga: Shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/jspui/bitstream/10603/66859/7/07_chapter%202.pdf

Sanstha, B.S. (1999-2017). Akshardham-visitor information. Retrieved February Friday, 2017, from akshardham: akshardham.com

R.Arora (2003). ‘Riggs Administrative Ecology ‘ in B.Chakrabarty and M.Bhattacharya (eds.) Public Administration : A Reader, New Delhi , Oxford University Press, pp. 101- 132

Deleuze G. and Guattari F.(1983), Anti- Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota press.