Revisiting Ufa: Pakistan’s Untenable Misinterpretations – Analysis

By Divya Kumar Soti*

In his press conference in the afternoon of August 23, Pakistan NSA Sartaj Aziz accused India of setting diplomatic pre-conditions for the National Security Advisor-level talks and trimming down the agenda for the talks in violation of the Ufa joint statement. Stressing upon the second paragraph of the Ufa joint statement, Aziz appealed to global think tanks to look into the Indian position of keeping the NSA level talks exclusively centered upon terrorism. Reportedly, Pakistan has also contacted United Nations with the same representation.

The second paragraph of the Ufa statement reads as follows: “They (both prime ministers) agreed that India and Pakistan have a collective responsibility to ensure peace and promote development. To do so, they are prepared to discuss all outstanding issues.” According to Sartaj Aziz, proceeding upon this Pakistan proposed a “comprehensive agenda” for NSA-level talks covering outstanding issues particularly the issue of Jammu and Kashmir.

In her press conference later in the day, India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj said that Pakistan’s insistence on Sartaj Aziz’s planned meeting with Hurriyat separatists in New Delhi as well as the attempts to broaden the agenda of NSA level talks is in violation of the spirit of the Shimla agreement and Ufa joint statement.

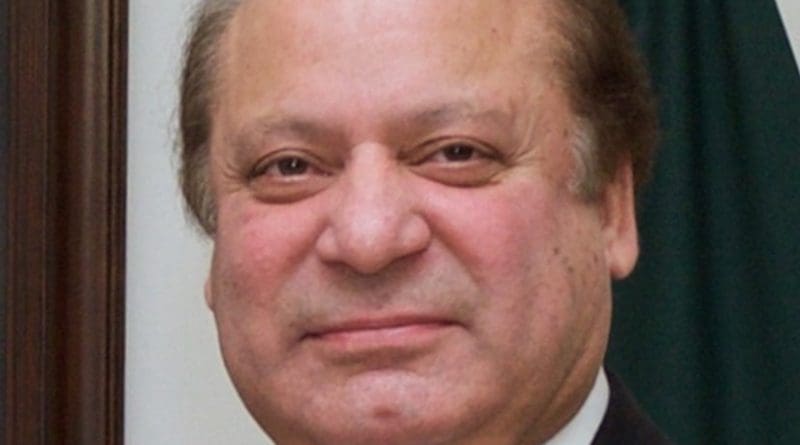

In view of all this, it becomes necessary to review the Ufa joint statement as well as the circumstances in which Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Pakistani counterpart Nawaz Sharif met at Ufa. The reference point shall be that which of the two countries should have insisted upon the clarification of Hurriyat red line in the Ufa Joint Statement itself. A closer look at the events preceding and accompanying the July 10, 2015 Ufa talks shall make things clear. Last year, India cancelled the Foreign Secretary-level talks when the Pakistani High Commissioner in New Delhi Abdul Basit invited Hurriyat separatists for prior consultations. It was clear that India won’t engage with Pakistan anymore if it tries to admit Hurriyat as a third party on Kashmir either directly or indirectly.

Pakistan itself acknowledged this red line when Basit postponed an Iftaar party for Hurriyat leaders this year so that it does not closely precede or succeed the Modi-Nawaz meeting in Ufa. So by insisting upon Sartaj Aziz’s meeting with Hurriyat separatists, Pakistan was deliberately going back upon its acknowledgment of the red line that such interactions with Hurriyat shall not coincide with India-Pakistan bilateral engagements.

However, it is ironical that Aziz accused India of violating the democratic rights of Hurriyat separatists. Pakistan should ask itself whether it would allow Gilgit-Baltistan (a part of the historical state of Jammu & Kashmir) activists, who are calling for an end to Pakistani occupation, to meet the Indian envoy in Islamabad. Leave alone allowing Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan separatists to meet foreign envoys, Pakistan does not even allow its own citizens to discuss the plight of these regions amongst themselves.

This year in May, Pakistani authorities disallowed a seminar on the topic “Baloch Missing Persons and the Role of the State and Society”, and its venue, Karachi University’s Arts Auditorium was sealed. The session was somehow organized by social activists in the Karachi University lobby as Pakistani security forces searched through the cars to stop invitees not connected with the university.

In China, Pakistan’s closest ally, it is unthinkable for any foreign envoy to have a meeting with Tibetan or Uighur activists. China also objects to foreign leaders meeting the Dalai Lama in their own countries. The Uighur Muslims have consistently alleged encroachment upon their religious freedom by Chinese authorities, but Pakistan has always maintained a conspicuous silence.

Pakistan has been constantly referring to acquiescence of the A.B. Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh governments in allowing the meetings of Pakistani representatives with Hurriyat separatists. What Pakistan fails to understand is that the Modi government is not bound by such precedents. The Modi government has every moral and legal right as well as duty to discontinue any practice which it considers as being detrimental to the sovereignty and integrity of India as the Indian Constitution allows restrictions on freedoms on this ground. For this purpose it is entitled to its own judgment and not bound by the judgments of the previous governments.

Pakistan’s stress upon the second paragraph of the Ufa joint statement (quoted above) is also misplaced in view of the rules of interpretations of such instruments. Legal and diplomatic instruments are to be read as a whole for the purposes of interpretation and special provisions exclude the general ones. It is correct that second paragraph of the Ufa joint statement constitutes the intent of both sides to discuss all outstanding issues. But it does not lay down any framework for such discussions. The only framework which the Ufa statement lays down relates to five issues, namely: terrorism, border firing, release of fishermen, religious tourism and expedition of 26/11 trial. The meeting of the two NSAs was to be specifically related to “all issues connected with terrorism”.

Clearly, the Ufa joint statement envisaged the taking up of the issues in a stage-wise manner and laid down a special framework for first taking up of issues which have often killed the composite dialogue between the two countries. The Ufa statement tried to build upon the past experience that the composite dialogue process should be sustainable to reach any conclusion, and for it to be sustainable, issues connected with terrorism and border violence must be addressed on priority basis before the two countries proceed to take up the next ones.

The spirit of Ufa was not comprehensiveness; it was about prioritizing more important issues and clearing up the landmines which have always killed the Composite Dialogue process.

*Divya Kumar Soti is a national security and strategic affairs analyst based in India. He can be contacted at [email protected]

In the absence of acceptable mediation, such bilateral engagements allow either party to realign their priorities at a given moment to better reflect their strategic interests. This will lead to the inevitable result experienced here. To summarize, composite dialogues are ineffective if both parties do not perceive the utility of such engagements and this is the reason the dialogues has failed as they’re no compelling reasons for either party to continue down this path.