Sentencing Female Teacher Sex Offenders – OpEd

By Center for Justice Research

By Jack Sevil

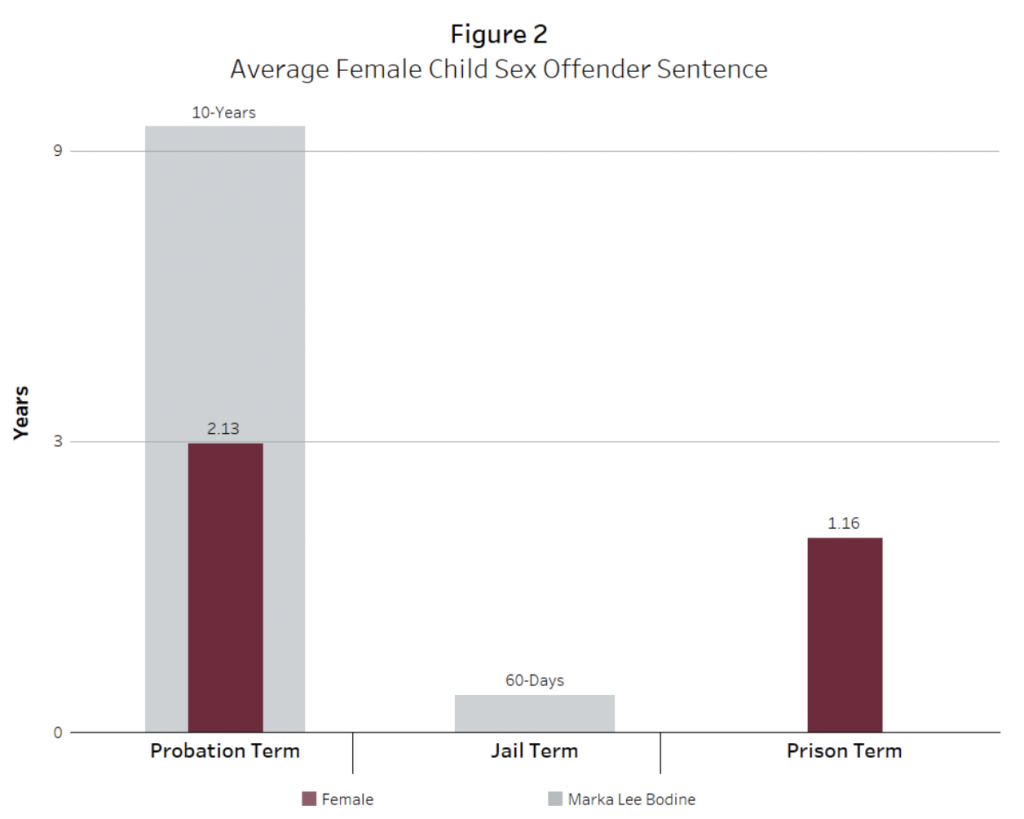

A former Tomball Independent School District middle-school teacher has been sentenced to 60-days jail with a 10-year probationary period for aggravated sexual assault. The offender, 31-year-old female Marka Lee Bodine, is now also a registered sex offender and awaits jail following the recent birth of her child. The victim – whose identity has been protected – was a 13-year-old male student of Bodine, and is not the father of Bodine’s child.

Contemporarily, sexual abuse between students and teachers is commonplace for regular consumers of news media. Conversely, sentencing – most often – of female teachers who sexually abuse students remains jarring to consumers of news media.

Bodine’s charge was first-degree felony aggravated sexual assault. Aggravated herein meaning Bodine’s charge necessitated greater punitiveness because the victim of sexual assault was under 14-years of age. Further, the guideline minimum sentence for first-degree aggravated sexual assault is 25-years imprisonment. Though the presiding Judge Greg Glass chose to depart downward from a 25-year minimum sentence.

Without explanation for Judge Glass’ downward departure when sentencing Bodine, news media speculated about possible confounding factors. For instance, Bodine’s sex was speculated as influencing Judge Glass’ use of judicial discretion to sentence Bodine to only 60-days jail.

The Center for Justice Research (CJR) aimed to investigate the relationship between the sex of child sex offenders and sentencing. While it is generally understood that males receive more punitive sentences than males, the current work presents a unique opportunity. That is, much is known of Bodine’s case despite little being known about why Judge Glass downward departed during sentencing. As such, the current work will utilize Bodine’s sentence as a case-example to compare against similar crimes within Texas.

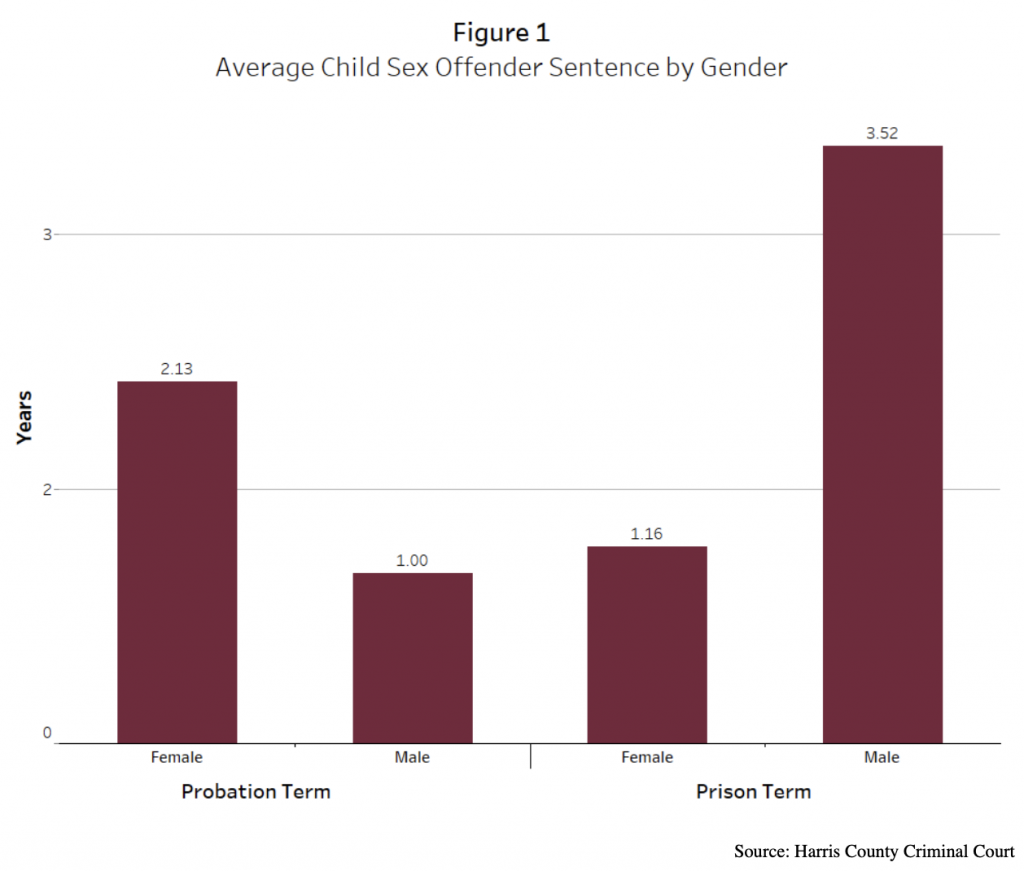

The CJR obtained information for analyses relevant to 580,860-criminal defendants sentenced within Texas, United States of America (USA) from 2012 to 2018. As demonstrated by Figure 1, prison sentences of 369-female (3.27%) child sex offenders analyzed were on-average more than three-times lower than the 10,928-male (96.73%) child sex offenders analyzed. Conversely, female child sex offenders on-average serve more than two-times longer probation sentences. Though, unlike Bodine, the average jail sentence for both females and males was 0-years.

Figure 2 demonstrates Bodine’s probation sentence is more than four-times harsher than the average sentence of female child sex offenders in Texas. Further, Bodine will serve 60-days jail whereas on-average female child sex offenders do not receive jail sentences. Rather, on-average female child sex offenders within Texas serve 1.16-days in prison. Figure 1 is not surprising, as previous work demonstrates similar sexual disparities in sentencing; however, Figure 2 demonstrates Bodine’s sentence is both harsher and more lenient than the female average for similar crimes.

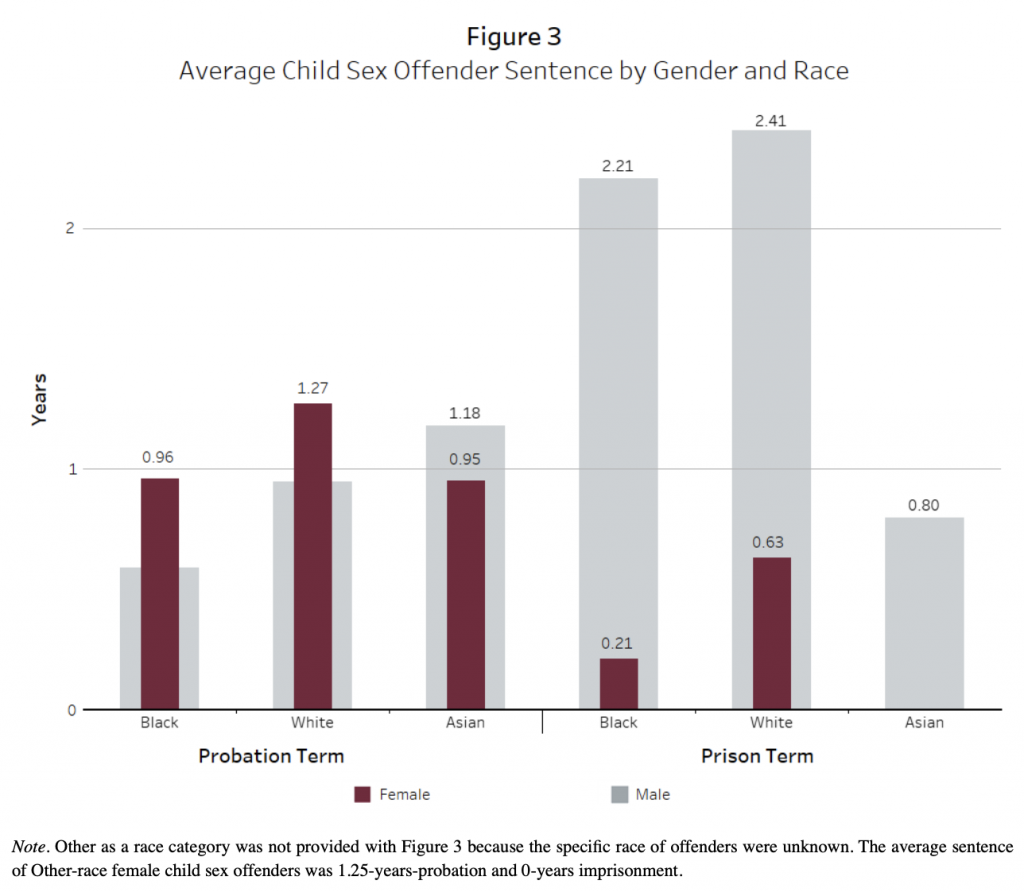

Additionally, Figure 3 demonstrates the average sentences of Harris County female child sex offenders by race. Herein, white female child sex offenders on-average receiver longer sentences than any other race. Moreover, jail time in years is absent from Figure 3 because unlike Bodine, on-average female child sex offenders within Harris County are not sentenced to jail.

Given sexual disparities in child sex offenders sentences demonstrated herein – without additional context of each case – Bodine was sentenced leniently than males who commit similar crimes. Simultaneously, Bodine was sentenced more harshly than other females who are sentenced for similar crimes. Good faith dictates inferring variations exist in the severity of defendants’ crimes which cause sexual sentencing disparities, but nonetheless measurable sentencing disparities exist.

Though without good faith, contention is ongoing regarding why sexual sentencing disparities amongst child sex offenders exist. Further, such contentions meet different resolutions within academia, government, media, and the public. Though, every resolution is to an issue which is undefined. This is because information required to delineate the cause of sexual sentencing disparities amongst child sex offenders are often deemed vaguely sacrosanct to court privacy. This issue is avoidable via disclosure of all possible information with necessary redactions.

Without all possible information, new solutions cannot be proposed. Rehashed conclusions thereafter are predicated on demographic variables such as sex, whereas other factors are possibly more important. Alongside court information disclosure being imperative to new solutions for sentencing disparities, disclosing information to the public represents a government revenue opportunity. For instance, it reportedly costs anywhere between $23 and $80-per hour for analysts to retrieve information upon request via the Freedom of Information Act 1967.

Further, law enforcement agencies and judges will lesser undergo criticisms for sentencing disparities in circumstances wherein such criticisms are unduly. That is, the newly available information from courts will change how sentencing hearings such as Bodine’s are reported. This is because if every word of Bodine’s court case and sentencing was available to the public – transcribed with necessary redactions – supposing about Bodine’s sex influencing her sentence may have been unjustifiable.

Further, disclosing all available information of court proceedings benefits the public generally via creating greater freedom of information. Ideally, the Freedom of Information Act 1967 negotiates circumstantial transparency between the public and the USA Government. Though, the Freedom of Information Act 1967 provisions for a select portion of government information which should be publicly available.

As such, the Freedom of Information Act should be amended to remove requirements of requests for information. Instead, already existing infrastructure which stores and releases information not harmful to personal or national security should also publicly publish all-such data. The only additional required infrastructure therein being a government webpage and accompanying security and maintenance.

Similar webpages – referred to as ‘portals’ – have existed in the USA Senate since signed into law by President Barack Obama during 2016. That is, the Freedom of Information Improvement Act 2016 established a centralized webpage wherein the public could request access to government information from all applicable government agencies; however, the public should not have to request such information.

Without public access to all possible court information, causes of existing sexual disparities amongst sentences of child sex offenders evade the public. As long as non-disclosure of court information continues, sexual disparities in sentencing of child sex offenders will remain contentious with potentially useless resolutions posited. Further, non-disclosure in favor of personal privacy is farcical from the USA Government while contemporary laws utterly disregard the concept. Amending the Freedom of Information Act 1967 similarly to the Freedom of Information Act Improvement Act 2016 to remove requisite requests of access is necessary.

*About the author:

- Jack Sevil is a Research Analyst for the Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University. His research interests pertain largely to the intersection of human rights and criminal justice. Jack received his Master of Justice and Criminology in 2020 from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne Australia.