How Pre-Abrahamic Polytheists Degraded Sacred Scriptures – OpEd

The Torah and Qur’an flood narratives are a Monotheistic moral lesson rebuilding of a famous degraded Mesopotamian Polytheistic amoral flood narrative. Although many flood stories exist throughout the world, the biblical parallels to the Mesopotamian flood story are particularly close. A connection between the two stories was in fact already proposed two thousand years ago by the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Josephus (in Antiquities of the Jews, 1.93 and Against Apion 1.130), who clearly regarded them as narrating the same event.

Josephus knew the Mesopotamian flood story from the work of the Babylonian priest Berossus (ca. 280 B.C.E.) who had had access to Babylonian cuneiform sources and recounted Babylonian history in Greek for the Hellenistic world.

In the work of the Babylonian priest the flood hero Xisouthros is the tenth in a line of long-lived antediluvian kings, just as in Genesis 5, Noah is the tenth in a line of long-lived antediluvian patriarchs. The names are quite different, but all of Berossus’s names are attested for antediluvian kings in earlier versions of the Sumerian King List.

Also the name Xisouthros is a Greek form of the Sumerian name Ziusudra, the flood hero in a Sumerian version of the flood story from about 1600 B.C.E. This version is ancient enough to have been known by Prophet Abraham and used in the Biblical text about Noah.

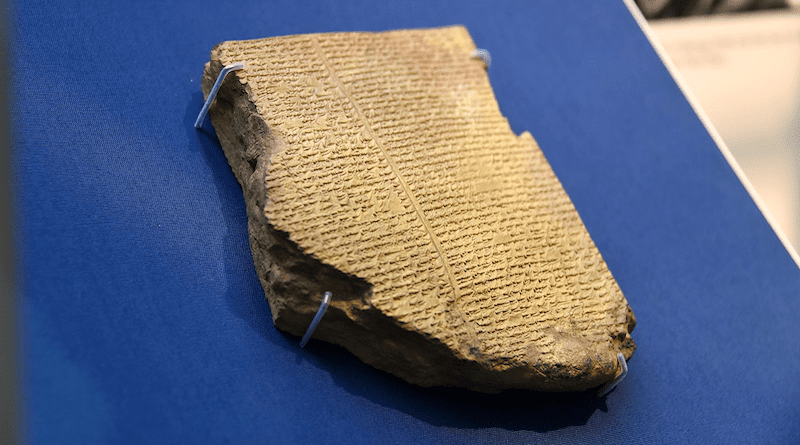

In the Gilgamesh epic, arguably the earliest great piece of world literature, Gilgamesh, king of Uruk (biblical Erech, modern Warka in Iraq), after various adventures and the death of his best friend Enkidu, is on a quest for immortality. In the account of the flood in tablet 11, which was not part of the original Old Babylonian Gilgamesh epic, the flood hero Utanapishti recounts to Gilgamesh the story of the flood.

The flood story recounted by Utanapishti is as follows. The god Ea warned Utanapishti of an imminent flood and instructed him to build a boat to preserve life. The chief god, Enlil, then brought a flood upon the world which lasted six days and seven nights, following which the ark landed on Mt. Nimush (in modern Iraqi Kurdistan).

After another seven days, Utanapishti released a dove, which returned, then a swallow, which also returned, and finally a raven, which did not return. The flood clearly now over, Utanapishti offered a BBQ offering on the mountain, and the gods gathered round like flies to savor the wonderful smell of the offering. Finally, Utanapishti was made immortal.

Archaeologists also discovered an even earlier version of the Mesopotamian flood narrative, the Atrahasis epic. The Atrahasis epic is known in various recensions dating from the second and first millennia B.C.E. None is perfectly preserved, but the best preserved is an Old Babylonian version dating from the seventeenth century B.C.E. This was discovered at Nineveh and has since been in the British Museum, but the tablets were not all put together and properly understood till the 1960s.

The story of the deluge comes at the climax of a larger work. Originally, we read that the gods were like men, undertaking labor on earth, but finally humans were created in order to relieve the gods of work. However, as human beings multiplied in number, so their noise increased, and this disturbed the sleep of the chief god, Enlil. In consequence, Enlil brought first a plague, then a drought, next a famine, and finally a flood to destroy human beings and their noise.

Another god, Enki (=Ea), warned Atrahasis (meaning “very wise”) of the imminent arrival of the flood in seven days, and he built a boat off wood, reeds, and pitch (cf. Gen 6:14). The flood came and lasted seven days and nights. When it ended, Atrahasis offered sacrifice, and the gods gathered round like flies to savor the smell.

Following the deluge, a new order of human society was instigated by Enki. This new order allowed humanity to continue in existence, but various constraints were placed on human reproduction in order to prevent numbers getting out of control again.

It is generally accepted that the Gilgamesh flood story is based on an earlier version recounted in Atrahasis (Utanapishti is even called Atrahasis twice, in Gilgamesh 11.49, 197.) After the flood is over, the One God of the Torah promises to not bring about another comparable flood. There is nothing comparable to this at the end of the flood story in the Gilgamesh epic. However, toward the end of the Atrahasis epic, the god Ea states: “Henceforth let no flood be brought about, and let people last forever.”

Both polytheistic texts degrade the original monotheistic narrative morally from Noah’s Biblical text which was originally monotheistic as the one God brings the flood, and saves the flood hero and the others on the ark. The originally narrative text had also been ethicized, insofar as the flood was a punishment for human sin, not just to human overpopulation and noise, as in Atrahasis or just an amoral whim of the god Enlil, as in Gilgamesh. Polytheistic gods often challenge and oppose each other and it is easier to explains good and evil events by saying they come from different gods who often fight with each other.