Has Japan Twisted To The Right? – OpEd

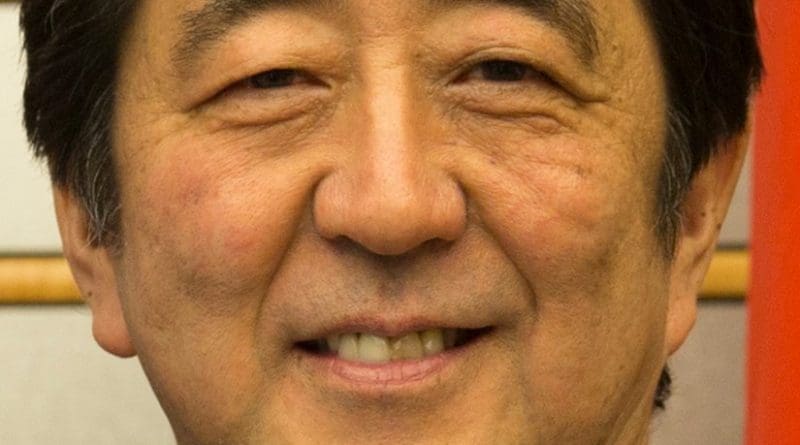

What Japan’s new Prime Minister Shinzo Abe envisions as the correct path, should not necessarily be understood as a ‘rightist’ path. If the victory of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in the recent parliamentary elections means a dramatic shift to the right, then it means that Japan has merely been brought to the centre of the political spectrum because it has been far too leftist in the post-war years. To this end, Abe’s nationalistic and hard-line right-wing nature is being overplayed by certain elements. While the LDP’s victory was greeted with enthusiasm by countries like the US, India, Indonesia, and other Southeast Asian countries, it comes with no surprise that Beijing and Seoul have been concerned with the new development because of the rise of a nationalist power in Tokyo.

In the wake of Abe’s return to power, several local and international media outlets and security analysts interpreted LDP’s victory as a dramatic transformation in Japanese politics with a massive swing to the nationalist right. Apart from the fact that Abe’s election campaign echoed the nationalist mantra, this alone is inadequate to establish that Japan as a nation has fully embraced the right-wing ideology. In the immediate aftermath of the elections Abe admitted that the LDP did not necessarily regain the confidence of all Japanese voters, and rather, their victory was underpinned by the rejection of the Democratic Party of Japan who was ‘politically confused’. Although Abe may seem to be hawkish in comparison to his predecessors, the claim that Japan as a whole twisted to the right is an over-simplification and disregards the larger political landscape which the country is currently placed under.

The Hawk Versus Regional Paranoia

Beijing and Seoul’s apprehensions towards Abe’s seemingly hawkish agendas are understandable, but are narrow-sighted and cannot be substantiated. One of the LDP’s campaign goals was to revise parts of the country’s war-renouncing constitution, specifically the peace clause as envisaged in Article 9. Abe contends that there is a contradiction inherent in the current security arrangement in Japan, where the security forces are recognised as a Self-Defense Forces (SDF) domestically, while internationally it is being projected and deployed as an armed force that operates legally under the Geneva Conventions.

In reality, Japan’s defense expenditure is said to be the third largest in the world and the forces are fully equipped with sophisticated weaponry. He feels that this duality undermines the legitimacy of Japan as a responsible contributor to regional stability and thus needs to be addressed. Abe’s solution is to elevate the status of the SDF to a national army. This proposal seemed to have stirred the paranoia of China and South Korea, who still reiterate the vivid memories of Japan as an aggressor state in the pre-war years.

Paranoia aside, this proposal should be of no threat or concern to any international actors. In the current political setting, it is a fundamental right and a criterion of every sovereign nation to possess an army. Over six decades after the war, there is no reason why Japan should be an exception to this rule. Amidst the increasing regional security threats including the recent North Korean rocket launch and the rising tensions between the neighbouring countries over territorial disputes, the LDP’s proposal seems to be a natural response in adopting a more proactive defense posture. Japan equally has the right to claim its territory through the strategic use of soft and hard power just like any other sovereign country would do. The elevation of status of the SDF is not a mere name-change, and it holds significant implications to the regional security arrangements and geopolitical balance. Given that much concern has been raised by China and South Korea at the preliminary stage of the proposal, this in itself demonstrates the potential deterrent power a ‘militarised’ Japan would possess in the future regional security scene. What is more essential is to observe Japan on a long-term basis and to assess how its military attitude is managed in the years to come. It is too premature at this point to conclude that Abe’s apparently hawkish proposal is an indication of Japan’s intent to return to the aggressive pre-war military posture.

Re-defining Japan

Abe is rather outspoken about his visions on the regional security relations. Although he boldly asserts Japan’s ownership of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu and Takeshima/Dokdo islands as ‘non-negotiable’, he certainly understands the stake of jeopardising the already strained relationship vis-à-vis Beijing and Seoul. The Prime Minister acknowledged the importance of improving the Sino-Japanese relationship as a step to ensure stability in the region, and that both countries need to forge a strategic partnership based on ‘equal’ grounds.

Additionally, Abe resolved to strengthen its alignment with the US, as well as increase Tokyo’s security ties with New Delhi, Canberra, and other ASEAN capitals. The new regime seeks to engage in a more proactive regional politics based on its strategic interests. This marks a great shift from the traditional approach where the political discourse on diplomacy and security relations was largely driven by sustaining ‘friendly’ relations through submission. As Abe’s approach on security issues takes on a different course from the past, Japan’s role in regional politics will be re-defined in the coming years.

At this point in time, it is reductionist to associate the emergence of popular nationalism in Japan as a dramatic tilt to the right. The policy reforms as envisaged by the LDP are seemingly groundbreaking and hawkish; however, it is a natural and a moderate response to the current political climate which confronts Japan. An attempt to re-establish its role in the region by asserting a proactive diplomatic attitude is not necessarily a rightist move.

Abe’s nationalist policies do not mean that he will allow Japan to run amok by re-enacting the memories of the pre-war past. He will carefully walk a diplomatic tightrope so as not to unnecessarily jeopardise the already strained relations with some of the neighbouring countries. Concerned policymakers and analysts therefore should not be blinded and misguided by the rightist rhetoric which is being overplayed to describe the new regime. A long-term assessment is imperative because premature interpretations can lead to an inaccurate analysis of the ground situation. This may potentially perpetrate strategic blunders which can be fatal to the national interest of all concerned regional and global players.

Author Bio:

Sara De Silva is currently a PhD Candidate researcher at the Faculty of Law in University of Wollongong, Australia. Previously she was an Associate Research Fellow at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), Singapore.