Why Populism May Only Grow In The 2020s – OpEd

By Arab News

By Andrew Hammond*

Controversial Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro on Wednesday celebrated his first anniversary as leader of South America’s most populous and economically important democracy.

Bolsonaro’s unexpected rise to power epitomizes the growth of populism in the 2010s, with research suggesting a staggering 2 billion of the world’s population are now governed by populist leaders, a situation with major implications not only for politics but also economics.

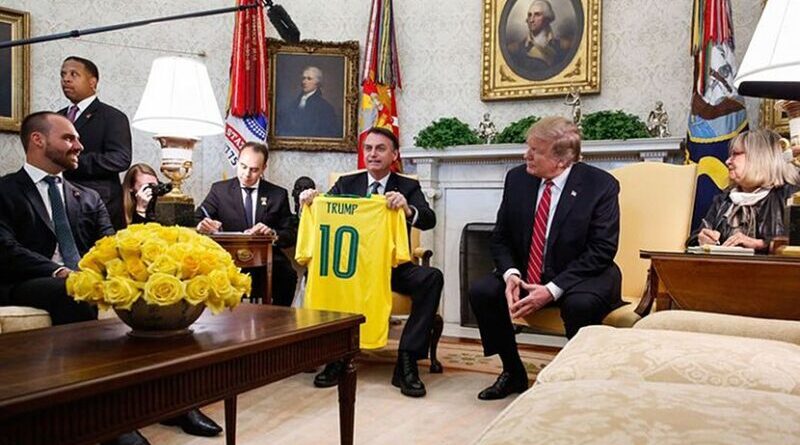

While high-profile conservative populists such as Bolsonaro and US President Donald Trump have dominated headlines in recent years, the same research shows that the growth of populism is a much broader, diverse phenomenon.

The upending of the international political order is highlighted by the Global Populism Database, which has monitored the two-decade rise in populism by analyzing speeches by key leaders in 40 countries. Its research found that that 20 years ago populist leaders governed in only a handful of states with populations over 20 million, including Italy, Argentina and Venezuela.

This previously relatively small “populist club” has grown rapidly, especially since the 2008-09 global financial crisis. The proliferation of populist leaders has been particularly marked in recent years, with the election not only of Bolsonaro and Trump, but also many others from the Americas to the Asia-Pacific, including Indian leader Narendra Modi whose Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party won a landslide re-election last year in the world’s largest democracy.

Certainly, there are still some limits on the rise of populism, with a significant number of leading countries, including Canada, France and Germany, never having a government head who has used populist rhetoric in the time period under review. However, even in these states, the share of the vote going to populist political parties has tripled since 1998.

However, far from being unique in history, this latest wave of populism is just one of several in recent centuries. In the past, populism has been a recurrent phenomenon in some countries, including the US.

Andrew Jackson, a Democrat who served as US president from 1829 to 1837, earned the nickname “King Mob” because of his populist rhetoric.

Despite their different party affiliations, Jackson often draws comparisons with the Republican Trump — and for good reason.

Like Jackson, Trump is an insurgent who has tapped into popular anger with the political establishment, especially among working class voters angry about multiple issues, including significant increases in income inequalities.

In the decades before 2016, these inequalities had only limited political consequences. US history shows that income and status differences are potential sources of political change that can be mobilized by politicians operating within parties or outside them. Trump, for instance, has energized groups that have lost income and job security, mainly unskilled and semi-skilled white men working in manufacturing.

Yet while this wave of populism is not unique, it has cast a bigger shadow than ever before, fueled in part by the international financial crisis and amplified by new technology such as social media. The Global Populism Database’s estimate that about 2 billion people are today governed by populist leaders represents a massive increase from 120 million at the turn of the millennium, with the research identifying leaders ranging from Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador to Modi as belonging in the populist camp.

Another key finding is how shades or flavors of populism differ across the world. The research found, for instance, that South America populism leans toward socialism (albeit with Bolsonaro as a key outlier), while populists in Europe tend to be right of center, although there are exceptions such as the rise of the leftist coalition Syriza in Greece.

Looking to the future, a key question is whether this wave of populism will intensify or fade out, especially if the global economy delivers sustainable growth during much of the 2020s. While that remains unclear, critics of populists point to their often weak record in power as one sign that the current era of populism will not endure.

Bolsonaro and Trump, for example, are suffering from weak poll ratings driven in part by scandals and the failure to deliver on much of their policy agendas. Yet there is a strong possibility both could get re-elected in the 2020s, benefiting from loyalty from a core base of supporters, the possibility of a robust economic backdrop to their campaigns, and fractures within their political opposition.

More than a decade after the global financial crisis, this 21st-century wave of populism may not yet have peaked. A good indicator of the direction of travel in the 2020s could well come in November’s US presidential election with a second term for Trump likely to generate new inspiration and self-confidence for populists across the world.

- Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.