The Global Vaccine Race Against Time And Variants – Analysis

Despite pandemic fatigue and complacency in too many countries, vaccine inequality will penalize poorer economies, which are also likely to prove more vulnerable to new variants.

In the past month or two, too many countries struggling with COVID-19 have been lulled into fatigue and complacency, despite holiday spikes. Since vaccination drives have begun, the assumption is that pandemic challenge is pretty much behind.

Both assumptions are flawed. Vaccine drives in emerging and developing economies will occur significantly later than in advanced economies. And by then, new variants may test vaccine effectiveness.

The net effect? When high-income economies will eventually open their borders, middle-income economies will be exposed to new strains that could prove more contagious, more protracted and more lethal. And the vulnerability of low-income economies will prove even higher.

Vaccine inequality penalizes poorer economies

In early February, or two months into the global rollout of coronavirus vaccines, a handful of high-income economies in the West had hoarded 80 percent of the vaccination doses used thus far. There were almost 130 countries with 2.5 billion people that had not been able to administer even a single dose.

The disparity is far greater if China, an upper-middle-income nation, is excluded. In that case, middle-income nations represent nearly half of global coronavirus cases, but just 17 percent of doses administered.

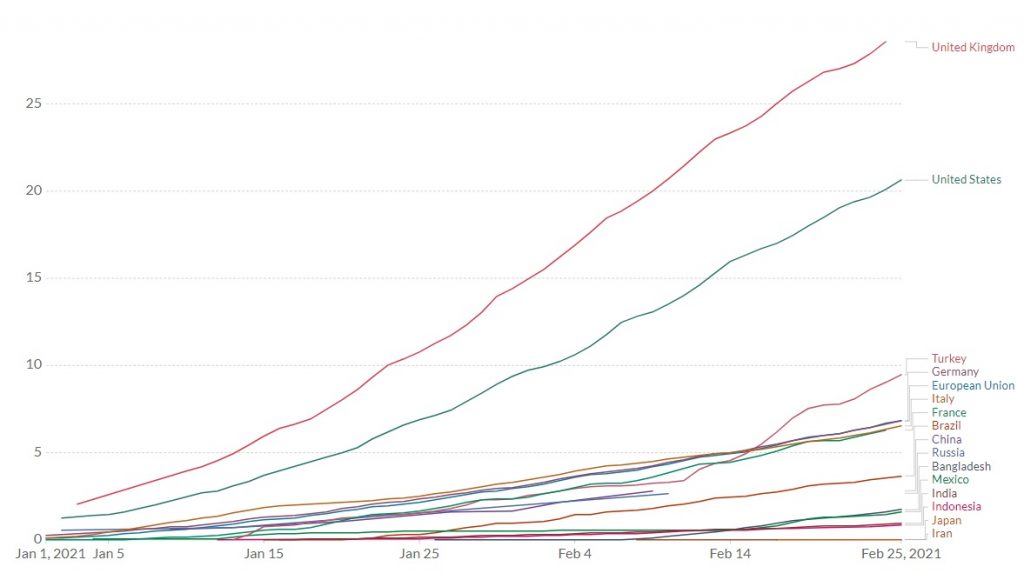

In economies of more than 50 million people, two high-income economies, United States and United Kingdom, have been most active in hoarding vaccines, after each mismanaged the pandemic. They are followed by Turkey, Germany, EU, Italy, and France. Except for Turkey, most middle-income countries come only thereafter, including China, Russia, Bangladesh, Mexico, India and so on (Figure 1).

Figure 1 COVID-19 Vaccine Doses*

New variants could prolong the crises

Thanks to the failure of multilateral cooperation in the course of the global pandemic, the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths is far higher than initially anticipated. In turn, huge numbers contribute to the rising probability of adverse strains.

In recent months, new variants of the original virus have been spotted in several countries, including UK, Brazil, South Africa, and the US.

In December, scientists in the U.K. stated that the B.1.1.7 variant might be at least 50% more transmissible than the original one in Wuhan. Another variant of great concern is the mutation in South Africa because it seems to involve a genetic change that may help the virus evade the immune system and vaccines.

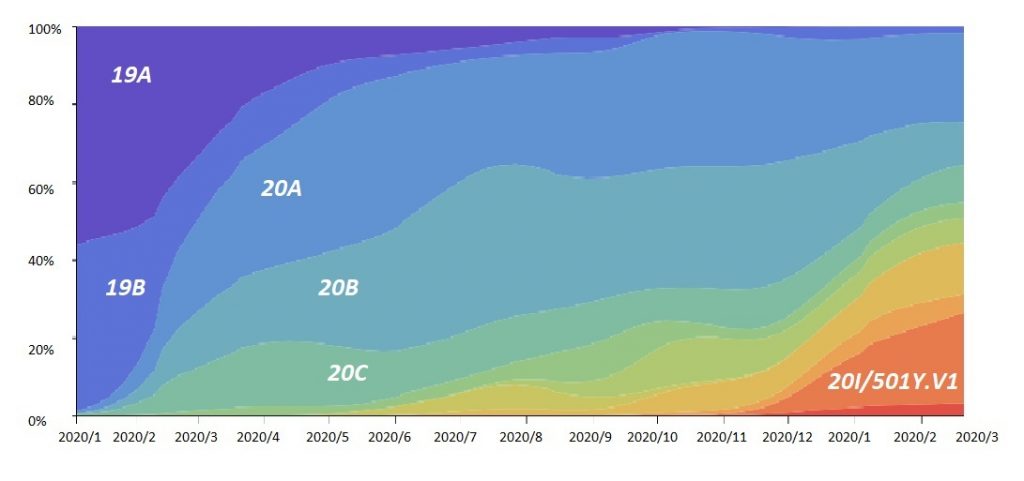

In January 2020, when the epicenter was still in Wuhan, the sequence 19A dominated existing cases. By March, new mutations had spread in the UK, US and elsewhere (19B and 20A etc.). After half a dozen other major strains, the British variant B.1.1.7 (also known as 20I/501Y.V1 as in the figure) is surging (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus

The nightmare scenario

In a few months’ time, the proportions may look very different, again. The British variant has surged in just two to three months. Even in countries that lead vaccination drives, critical mass will take months to achieve. Consequently, the frequencies of these viral clades may look very different by summer or fall 2021.

According to latest research, a Californian variant CAL2.0C has surged to account for more than half the cases in the state. By the end of March, it could cover 90% of Californian cases. Reportedly, infections from this variant, already detected in other US states, seem to produce a viral load double that of other variants.

The UK and California variants are each armed with enhanced capabilities. The concern is a nightmare scenario in which the two viruses could meet in a single person, and swap mutations. The outcome could be an even more dangerous strain.

The longer the global pandemic will last, the greater is the probability of more transmissible and lethal variants. Moreover, poorer economies are likely to remain more vulnerable to consequent human costs and economic damage.

Global COVID-19 cases exceed 115 million and deaths almost 2.6 million. Despite deceleration, daily new cases amount to 400,000 and daily deaths over 9,000 (7-day moving average).

The vaccine race is against time and variants – and time is not yet on our side.