Beijing’s Dangerous Flirtation With Hard Power Intimidation – Analysis

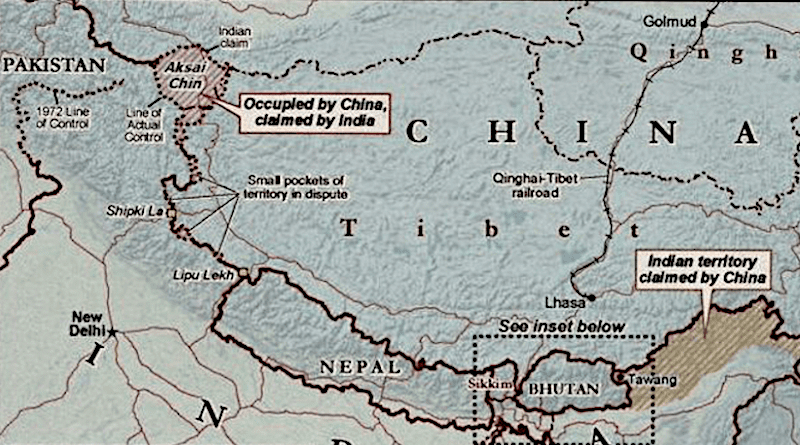

The 2023 China Standard Map has reaffirmed Beijing’s claim and dominance over Arunachal Pradesh, the Aksai Chin region, Taiwan, and the South China Sea, all of which remain disputed and controversial.

The new map has reaffirmed Beijing’s claim and dominance over Arunachal Pradesh, the Aksai Chin region, Taiwan, and the South China Sea, all of which remain disputed and controversial.

It includes maritime areas within Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) near Sabah and Sarawak, Brunei, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

The timing of this release has invited new scrutiny, in light of rising tensions in the region and upcoming geopolitical events that will compel Beijing to defend its interests and maximise its gains. A three-pronged factor is involved.

First, the recently approved USD500 million arms sales to Taiwan by the Biden administration has created further discontentment to Beijing, which has responded with the usual array of air and naval power intimidation and encirclement of the island in a new normal setting. Taiwanese Vice President and Presidential hopeful William Lai’s recent stopovers in New York and San Francisco, and his conventional hardline approach in Taiwan’s status and its ties with mainland China have added to the anger of Beijing.

Secondly, the release of the treated radioactive water from the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant has been seized upon by China to discredit Japan for convenient geopolitical gains, ignoring the obvious scientific evidence presented. This move to discredit Tokyo is an opportunistic and convenient pretext amidst growing tensions in the South China Sea and the growing counterbalancing forces and solidarity shown by the West and other players for Manila.

While Beijing has gained ground in Southeast Asia in elevating its soft power narrative and hard power postures to enhance trust, it continues to receive dwindling perception and acceptance in its Eastern neighbours.

Beijing’s worst fear of a consolidated security pact has come true, and the prospects of an expanded Camp David alliance or an enlarged Quad in the form of a mini or Asian Nato further accelerate Beijing’s hardened playbook and antagonizing behaviours.

Thirdly, the upcoming G20 Summit to be hosted by India remains another platform seen by Beijing as squeezing its rise and interests, in which China will need to build on its momentum of capturing the Global South and portraying itself as the undisputed leader of developing countries and in creating a new bulwark of anti-Western order and sphere of influence. India is increasingly being courted in a more holistic manner by the US led West, and China will want to send another two-pronged message to Delhi and Washington as well as regional neighbours in South and Central Asia that Beijing still holds the dominant economic and security upper hand, although its economic credentials have taken a serious hit.

The coming openings for China’s consolidation of influence and power expansion capabilities including the G-77 event and the recently concluded BRICS Summit are seen as crucial progressive tools for Beijing’s continuous anti-West narrative, in enhancing its flurry of strategic moves including the de-dollarisation movement and an expansive soft power and messaging capacity in upping the positive image of China and playing the victim card in painting the US led West as the main antagonist and instigator of tensions in chokepoints across the region.

The recent revelation by Meta on Tuesday that it had disrupted a disinformation campaign linked to Chinese law enforcement described as the largest known cross-platform covert influence operation in the world, remains a case in point. The influence network generated positive posts about China, while also attempting to spread negative commentary about the U.S. and disinformation in multiple languages about the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic, as reported by Meta.

This rising assertive path chosen by Beijing is based on a four-pronged factor. First, the fast closing window and timeframe for Xi to execute his ultimate Chinese Dream plan for Taiwan unification, with increased containment pressure and critical tech embargo by the West. This is worsened with Beijing’s internal economic decline and crisis now threatening to derail future efforts to have capable economic support in maintaining the potential of a protracted conflict with the West over Taiwan. The fast closing time frame is also exacerbated by the prospect of a sensational Trump return to power in 2024, which will further squeeze Beijing’s options and capacities in challenging the US especially in the realm of economic and military superiority.

Second, the increasing counterforce capacities by the US in thwarting Beijing’s moves have challenged Beijing’s near term capacities, with defence and security friendshoring efforts with Manila, Seoul, Tokyo, Hanoi, Delhi,Canberra and other regional players including Pacific Island states have further hampered Beijing’s power and influence expansion depth and momentum.

Thirdly, the declining effectiveness of deterrence and influence of ASEAN and its conflict prevention mechanisms in showing real and credible opposition to Beijing’s inroads, will give a clearer path for Beijing to reassert its push and further cementing its divide and conquer approach.

Fourth, in shoring up the legitimacy and capacity of President Xi in his internal consolidation of influence and power amidst new internal challenges and economic crisis. This is critical in laying the foundation of greater nationalistic sentiments and sense of Chinese pride and purpose, in superseding the current systemic challenges of the demographic crisis, economic slowdown, property and debt crisis, and the record unemployment among the youth.

Various confidence building measures and conflict prevention mechanisms have also failed to address the core causes of regional tensions, which have further escalated security dilemmas and arms races. Beijing has accused the West including the various deterrent mechanisms including Aukus and Quad as destabilising and the primary cause of regional tensions and arms build-up.

However, Beijing’s increasing hard power projection and intimidation are what caused regional jitters and fears in the first place, sparking the natural reactions of deterrent capacities and the unyielding drive to secure the importance of a rules based order and maintaining peace and stability.