Nasser And I – OpEd

By Uri Avnery

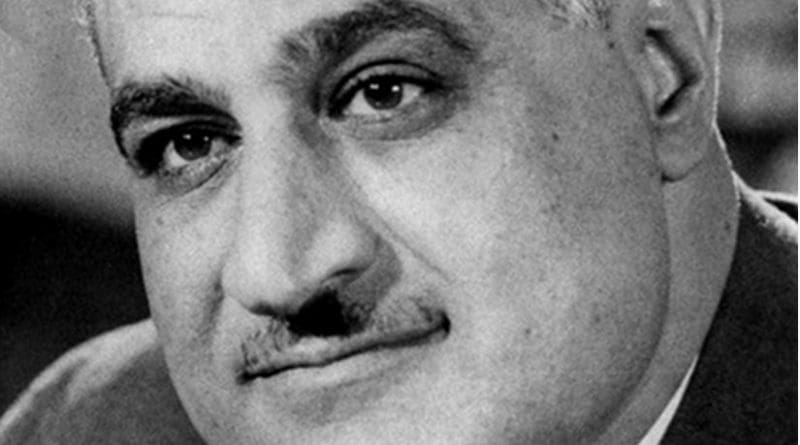

FORTY-FIVE YEARS ago Gamal Abd-al-Nasser died at the early age of 52. It is not an event of the past. It continues to have a huge influence on the present, and probably will on the future.

My meetings with him go back to 1948. I used to joke that “we were very close to each other, but we were never properly introduced!”

It happened like this: in July we were desperately trying to stop the advance of the Egyptian army towards Tel Aviv. The cornerstone of our front was a village called Negba. One evening we were told that an Egyptian unit had cut the only road to this kibbutz and dug in across it.

The company to which I belonged was a mobile commando unit riding on jeeps, each with two machine guns. We were ordered to storm the position and retake it at any costs. It was a crazy idea – you don’t use jeeps to attack dug-in soldiers. But the commanders were desperate, too.

So we advanced in the darkness along the narrow road until we reached the Egyptian position and were met with murderous fire. We retreated, but then the battalion commander joined us and led another attack. This time we literally overran the Egyptians, feeling human bodies under our wheels. The Egyptians fled. Their commander was wounded. As I later found out, he was a major named Gamal Abd-al-Nasser.

After that, the fortunes of war turned. We got the upper hand and surrounded an entire Egyptian brigade. I was a part of the besieging force when I was severely wounded. On the opposite side was Major Abd-al-Nasser.

FOUR YEARS later, Gingi called me in great excitement. “I must meet you immediately,” he told me.

Gingi is the Hebrew slang version of ginger, as the British call a red-haired person. This particular gingi was a small, very dark Yemenite. He was nicknamed Gingi because he had very black hair – that was our kind of humor then.

Gingi (his actual name was Yerucham Cohen) had served during the war as the adjutant of the Southern front commander, Yigal Alon. During the fighting, a short ceasefire had been arranged to allow both sides to retrieve the dead and wounded left lying between the lines. Gingi, who spoke excellent Arabic, was sent to negotiate with the emissary of the encircled force – Major Abd-al-Nasser.

As so happens, during their several meetings, a friendship sprang up between the two men. Once, when the Egyptian was very depressed, Gingi tried to comfort him and said: “Cheer up, ya Gamal, you will get out of here alive and have children!”

The prophecy was fulfilled. The war ended, the encircled brigade returned to a hero’s welcome in Cairo. Yerucham was appointed to the Israeli-Egyptian armistice commission. One day his Egyptian counterpart told him: “I was asked by Lieutenant-Colonel Abd-al-Nasser to tell you that a son has been born to him.”

Yerucham bought a baby suit and at the next meeting, gave it to his counterpart. Nasser sent back his thanks and an assortment of cakes from the famous Groppi Café in Cairo.

IN THE summer of 1952, the Egyptian army rebelled and, in a bloodless coup, sent the playboy king Farouk packing. The coup was led by a group of “Free Officers”, headed by a 51-year old general, Muhammad Naguib.

I published in my magazine a message of congratulation to the officers.

When I met Gingi, he told me: “Forget about Naguib. He is just a figurehead. The real leader is a fellow called Nasser!” So my magazine had a world scoop – long before anyone else in the world, we disclosed that the real leader was an officer called Abd-al-Nasser.

(A word about Arab names. Gamal is a camel, a symbol of beauty for Arabs. Abd-al-Nasser – pronounced Abd-an-Nasser – means “Servant of [Allah] the victorious”. Calling the man just Nasser, as we all did, conferred on him one of the 99 names of Allah.)

When Nasser officially became the leader, Yerucham told me in deepest secrecy that he had just received an astounding invitation: Nasser had invited him to come, privately, to see him in Cairo.

“Go!” I implored him. “This may be a historic opening!”

But Yerucham was an obedient citizen. He asked the Foreign Office for permission. The minister, Moshe Sharett, the renowned peace-lover, forbade him to accept the invitation. “If Nasser wants to talk with Israel, he must apply to the Foreign Office,” Yerucham was told. That was, of course, the end of the matter.

NASSER WAS an Arab of a new type: tall, handsome, charismatic, a spellbinding orator. David Ben-Gurion, who was already getting old, was afraid of him, and perhaps envied him. So he plotted with the French to overthrow him.

After a short voluntary exile in a Kibbutz, Ben-Gurion returned in 1955 to his post as Minister of Defense. The first thing he did was to attack the Egyptian army in Gaza. By design or mistake, many Egyptian soldiers were killed. Nasser, angry and humiliated, turned to the Soviets and received large shipments of arms.

Since 1954, France was facing a war of liberation in Algeria. Since they could not imagine that the Algerians would rise up against France of their own free will, they accused Nasser of inciting them. The British joined the club because Nasser had just nationalized the British-French company that ran the Suez Canal.

The result was the 1956 Suez adventure: Israel attacked the Egyptian army in the Sinai desert, while the French and the British landed in their rear. The Egyptian army, practically surrounded, was ordered to return home as hastily as possible. Some soldiers left their boots behind. Israel was intoxicated by this resounding victory.

But the Americans were angry, and so were the Soviets. US President Eisenhower and the Soviet President Bulganin issued ultimatums, and the three colluding powers had to withdraw completely. “Ike” was the last American president who dared to face down Israel and the US Jews.

Overnight, Nasser became the hero of the entire Arab world. His vision of a pan-Arab nation moved into the realm of possibility. The Palestinians, deprived of their own homeland which was divided between Israel, Jordan and Egypt, saw their future in such a broad nation and admired Nasser.

In Israel, Nasser became the ultimate enemy, the devil incarnate. He was referred to officially and in all the media as “the Egyptian tyrant”, and frequently “the Second Hitler”. When I proposed making peace with him, people considered me insane.

CARRIED AWAY by his immense popularity throughout the Arab world and beyond, Nasser did a foolish thing. When the Israeli Chief of Staff, Yitzhak Rabin, threatened the Syrians with invasion, Nasser saw an easy way to demonstrate his leadership. He warned Israel and sent his army into the demilitarized Sinai desert.

Everybody in Israel was frightened. Everybody except I (and the army). A few months before, I was informed in secret that a leading Israeli general had confided to friends: “I pray every night that Nasser will send his army into Sinai. There we will destroy it!”

And so it happened. Too late Nasser realized that he had walked into a trap (as my magazine announced in its headline.) To stave off disaster, he issued blood-curdling threats “to throw Israel into the sea” and sent a high-ranking emissary to Washington to plead for pressure to stop Israel.

Too late. After a lot of hesitation, and after getting explicit permission from President Johnson, the Israeli army attacked and smashed the Egyptian, the Jordanian and the Syrian forces within six days.

There were two historic results: (a) Israel became a colonial power and (b) the backbone of pan-Arab nationalism was broken.

NASSER REMAINED in power for another three years, a shadow of his former self. He obviously did some thinking.

One day my French friend, the renowned journalist Eric Rouleau, asked me to come urgently to Paris. Rouleau, an Egyptian-born Jew working for the prestigious French newspaper Le Monde, was at home with the Egyptian elite. He told me that Nasser had just given him a long interview. As agreed, he submitted the text to Nasser for confirmation prior to publication. After some consideration, Nasser struck out a crucial section: an offer to Israel to make peace. It was essentially the offer that formed the basis for the Sadat-Begin peace agreement nine years later.

But Rouleau had the full interview on tape. He offered to give me the text, so that I could transmit it to the Israeli government on condition of total secrecy.

I rushed home and called a leading member of the Israeli government, Finance Minister Pinchas Sapir, who was considered the most dovish member of the cabinet. He received me at once, listened to what I had to say and showed no interest at all. A few days later, during the Black September crisis in Jordan, Nasser suddenly died.

WITH HIM died the vision of pan-Arab nationalism, the rebirth of the Arab nation under the flag of a European idea based on rational, secular thought.

A spiritual and political vacuum was created in the Arab world. But nature, as we all know, does not tolerate empty spaces.

With Nasser dead, and after the violent end of his successors and imitators, Sadat, Mubarrak, Gaddafi and Saddam, the vacuum invited a new force: Salafi Islamism.

I have warned many times in the past that if we destroy Nasser and Arab nationalism, religious forces would come to the fore. Instead of a fight between rational enemies which can end in a rational peace, it will be the beginning of a religious war, which will by definition be irrational and allow for no compromise.

That’s where we are now. Instead of Nasser, we have Daesh. Instead of the Arab world led by a charismatic leader, who gave the Arab masses everywhere a sense of dignity and renewal, we are now facing an enemy which glorifies public beheading and wants to bring back the seventh century.

I blame Israeli and American political blindness and sheer stupidity for this dangerous development. I hope we still have enough time for it to be reversed.