Maritime Boundary Disputes And Maritime Law – OpEd

The importance of ocean is growing for states with rising dependence of states on sea-borne trade. With increasing globalization and maritime domain awareness, countries have started to streamline their maritime policies and are becoming concern about their marine resources given the strong belief that world economy is becoming ocean-based with rich trade and resource potential and termed as blue economy.

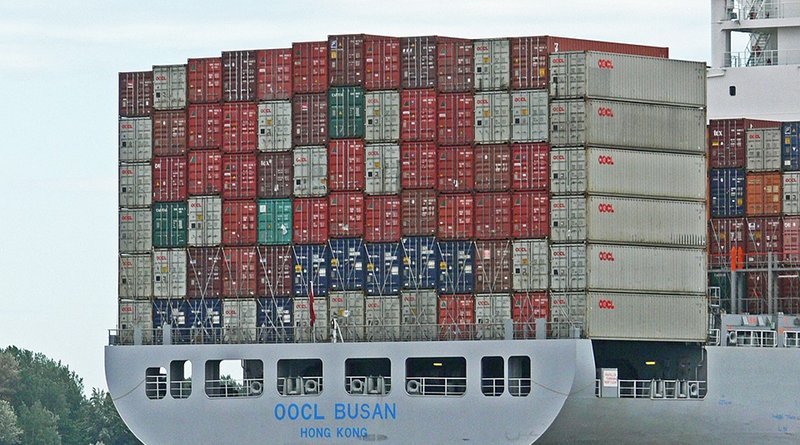

According to International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), “some 11 billion tons of goods are transported by ship each year. For an economic region such as the European Union, shipping accounts for 80% of total exports and imports by volume, and some 50% by value. As of 2019, the total value of the annual world shipping trade had reached more than 14 trillion US Dollars.”

This shows that the states’ dependence is increasing on maritime trade and transportation. Therefore, states are becoming equally concerned with other ocean based incentives and benefits such as marine and food resources. Littoral states are focusing on the exploration and exploitation of mineral and food resources of oceans. However, maritime boundary disputes are becoming the primary barrier to use marine resources for littoral states. Therefore, defined maritime boundary is prerequisite for every coastal state to utilize their maritime zones.

Generally a maritime boundary is a theoretical division of the Earth’s water surface areas using geopolitical criteria and it usually bounds areas of exclusive national rights over marine resources, including maritime limits, features and zones.

According to United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), “maritime boundary represents the borders of a maritime nation which serve to identify the edge of international waters.” Usually, a maritime boundary is demarcated at a particular distance from a jurisdiction’s coastline and it exists in the context of territorial waters, contiguous zones, and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). However, they do not cover rivers or lack boundaries as they are considered with land boundaries.

According to the UNCLOS, “the length of territorial sea is 12 nautical miles, contiguous zone is 24 nautical miles, and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is 200 nautical miles from the baseline.” Mostly, the maritime boundary dispute occurs due to the overlapping claims in different maritime zones and the contesting claims of sovereignty over the islands.

Every state claims jurisdiction of their territorial waters according to their suitability of interests. Resultantly, maritime disputes get emerge among different coastal states. The coastal states enticed in maritime disputes are endeavoring to settle their disputes through different methods of settlement. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea refers the peaceful method of the settlement of maritime dispute. For, states must be in consensus at first to accept the jurisdiction of this Convention. Otherwise, they will not be entitled to secure any advantages of the Convention.

Maritime boundary dispute settlement among states is an international but common phenomenon which is regulated by international laws. However, international law only helps the parties to settle their dispute if they ask for advantage of it by their consent, accession or agreement.

The UNCLOS is the Specific codification which was promulgated in 1982 and came into force in 1994 to regulate and facilitate maritime affairs among and between states. Article 287 of the UNCLOS states “when signing, ratifying, acceding, or at any time thereafter, a state shall be free to choose, by means of a written declaration, one or more of the following means for the settlement of disputes concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention: (a) The International Tribunal for the Law of Seas (ITLOS) established in accordance with Annex VI, (b) the International Court of Justice (ICJ), (c) an arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VII, (d) a special arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VIII for one or more of the categories of disputes specified therein.” These are the most acceptable means of maritime dispute resolution among coastal states.

Usually, coastal states also create another problem regarding selection of above mentioned means of settlement by UNCLOS. However, by accepting the jurisdiction and agreeing on any of the said means, many coastal states have resolved their maritime boundary dispute. Myanmar agreed with Bangladesh to settle the maritime boundary dispute by the ITLOS and the 40 years long-standing maritime boundary dispute between these two nations was settled.

Similarly, Australia and East Timor initiated a conciliation process, which was facilitated for almost two years under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Ultimately, two countries resolved their decade-long maritime dispute; made a pathway for future mutual benefits and set the example to oblige the international maritime law and governance. Given the increasing role and state’s reliability on international maritime laws, coastal states should promote maritime laws domestically and use the means and instrument of UNCLOS to resolve their maritime boundary disputes peacefully.

*Baber Ali Bhatti, Advocate Islamabad High Court and Research Fellow at Maritime Study Forum