Women In Combat: Issues For US Congress – Analysis

By CRS

By Kristy N. Kamarck*

Laws prohibiting women from serving in air and naval combat units were repealed in the early 1990s. However, until recently, it has been Department of Defense (DOD) policy to restrict women from certain combat-related units and military occupations, especially ground combat units. Despite the official policies barring women from ground combat positions, many female servicemembers have served in combat environments for much of the recent history of the U.S. military. In the past two decades of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, the lines between combat and noncombat roles have become increasingly blurred and as a result DOD’s exclusion policies have been called into question.

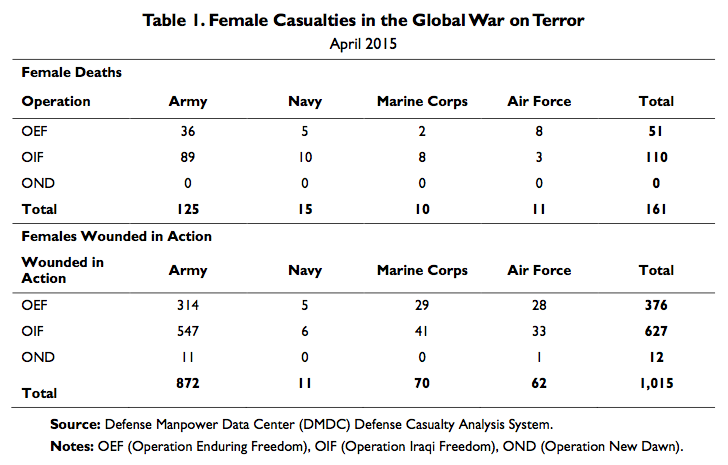

As of April 2015, 161 women have lost their lives and 1,015 had been wounded in action as part of Global War on Terror (GWOT) operations (See Table 1).1 In addition, in modern combat operations, over 9,000 women have received Army Combat Action Badges for “actively engaging or being engaged by the enemy,” and two have received Silver Stars for “gallantry in action against an enemy of the United States.”2

On January 24, 2013, the Secretary of Defense rescinded all ground combat restrictions for women and directed the military departments to implement the new policy no later than January 1, 2016.3 For DOD, implementation may require adjustments to recruiting, assignment, physical standards, and other personnel policies. As directed by the Secretary of Defense, the military departments have been conducting a series of reviews and studies to assess what changes or exceptions may need prior to the implementation deadline.4

Those in favor of keeping restrictions cite physiological differences between men and women that could potentially affect military readiness and unit effectiveness. Some also argue that social and cultural barriers exist to the successful integration of women into combat occupations and all-male units.

Those who advocate for opening all military occupations to women emphasize equal rights and argue it is more difficult for servicemembers to advance to top-ranking positions in the armed services without combat experience. In their view, modern weapons have equalized the potential for women in combat since wars are less likely to be fought on a hand-to-hand basis. In this regard, properly trained women would be able to perform successfully in combat and exempting them from serving in combat is unfair to men.

The military departments are required by law (10 U.S.C. §652) to notify Congress of changes that would alter occupational standards or open any new military career designators to women. Congress then has a 30-day (continuous in-session) review period upon receiving notification of the changes before DOD can implement them. Congress has authority to make changes in these matters and may consider additional issues including equal opportunity, equal responsibility (such as selective service registration), readiness and cohesion, and the overall manpower needs of the military.5

Background

While DOD policy has only recently opened combat roles to female servicemembers, women have been recognized for military service in combat since the American Revolutionary War. In 1776, Margaret Cochran Corbin became the first woman to receive a military pension from Congress for an injury sustained while helping to defend Fort Washington against British troops.6

However, for most of the history of the U.S. military, women’s roles were primarily clerical in nature or in support of military medical services. Women did not serve formally in the military until Congress established the Army Nurse Corps as a permanent organization within the Medical Department under the Army Reorganization Act of 1901.7 In 1908 Congress enacted language which led to the creation of the Navy Nurse Corps.8

World War II and the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act

In the earlier part of the twentieth century, the idea of enlisting women into the armed services was met with broad opposition from military commanders, Congress, and the public. However, the upsurge in manpower needs of World War II compelled Congress to open more service roles to women. In 1942, Congress opened the Naval Reserve to women9 and also created the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps for the purpose of

noncombatant service with the Army of the United States for the purpose of making available to the national defense when needed the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of this Nation.10

In 1943, Congress established the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve and made the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) a part of the regular Army on a temporary basis.11 By the end of the war nearly 400,000 women had served in armed services as members of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps, Women’s Army Corps (WAC), Navy (WAVES), Coast Guard (SPARs) and Marine Corps Women’s Reserves or with partner organizations like the American Red Cross, the United Services Organization (USO), and the Civil Air Patrol.12 Approximately 543 military women died in the line of duty during World War II and 84 others were held as prisoners of war (POWs).13

Following World War II, Congress made women a permanent part of the military through the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of 1948.14 This legislation included two exclusionary statutes prohibiting assignment of female members to duty in aircraft engaged in combat and to vessels engaged in, or likely to be engaged in combat missions.15 The legislation also limited the proportion of women in the military to 2% of the enlisted force and 10% of officers.

The All-Volunteer Force and Social Change

In the 1960s and 1970s, two major factors led to the expansion of the role of women in the armed forces. First, after the end of the draft and the beginning of the All-Volunteer Force in December 1973, the armed services had difficulty in recruiting and retaining enough qualified males, thereby turning attention to recruiting women.16 Second, the movement for equal rights for women led to demands for equal opportunity in all occupational fields, including national defense.

The limit on the percentage of women in the military was eventually repealed in 1967 and the number of women serving continued to grow through the next three decades.17 While the number of women in the military increased, various pieces of legislation in the 1970s also broadened the opportunities for female servicemembers. In 1974, the age requirement for women enlisting without parental consent was made the same as for men.18 In the next year, legislation was enacted that allowed women to be admitted to the three service academies, and the first women were admitted in the summer of 1976.19 In 1977, Congress directed the Secretary of Defense to submit to Congress a definition of the term “combat” and recommendations for expanding job classifications for female members of the armed forces.20 By 1978, women were permitted to be assigned permanent duty on noncombatant Navy ships, and up to six months of temporary duty on other ships.21

As women became more integrated into the military, the question was raised as to whether women should be required to register for the Selective Service. In 1979, when considering the reinstitution of Selective Service registration, the Senate Armed Services Committee cited legal and policy restrictions on women in combat as one of the reasons for differential treatment of men and women by Selective Service. In addition, the committee stated

The committee feels strongly that it is not in the best interest of our national defense to register women for the Military Selective Service Act, which would provide needed military personnel upon mobilization or in the event of a peacetime draft for the armed forces.22

As the percentage of women in service increased and they became more integrated into units serving in combat zones, there was a general lack of clarity on what role women could play in support of combat units and combat operations. One early example of this was during Operation Urgent Fury on October 25, 1983 when U.S. service personnel were sent for an evacuation of noncombatant American citizens on the island nation of Grenada. Four U.S. military police women arrived in Grenada shortly after the invasion and were promptly sent back to Fort Bragg, N.C.23 At Fort Bragg, Major General Edward Trobaugh, then-commander of the 82nd Airborne Division had removed all the females from the invasion Task Force. Following an intervention by Lieutenant General Jack Mackmull, then-commander of XVIII Airborne Corps, women were reattached to the unit and finally deployed to Barbados on November 2, 1983, to serve with the lead element of the Task Force while the rest of the Task Force deployed to Grenada the same day.24

The “Risk Rule” for Assignment of Women

In January 1988, the Department of Defense Task Force on Women in the Military noted that the varying definitions of a “combat mission” had led to inconsistencies between the military departments in the assignment of women.25 In response to the task force findings, DOD adopted a “risk rule” that excluded women from noncombat units or missions if the risks of exposure to direct combat, hostile fire, or capture were equal to or greater than the risks in the combat units they support. In this regard, the policy prohibited the colocation of women with combat units. For example, a female medic could be assigned to a noncombat support unit; however, if that unit was called on to provided support to a combat unit, the risk to the medical support unit would have to be less than the risk to the combat unit for the female servicemember to be assigned.

Also in 1988, the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office, GAO) noted a primary barrier to the expansion of the number of women in the armed services was that women were not allowed in most combat jobs, and were also barred from many combat-related jobs.26 The GAO reported approximately 15% of active duty positions were closed to women. Of the closed positions 41% were closed due to the risk rule’s collocation policy and 46% were classified as direct ground combat positions.27 The GAO’s report also noted that the primary rationale for excluding women from direct ground combat occupations included, lack of public and congressional support, lack of support by servicewomen, and lack of need given that there were an adequate number of men available to fill those positions.

During Operations Desert Shield/Desert Storm in Iraq and Kuwait, women played a more prominent role than in previous conflicts. Approximately 16 women were killed during the conflict and two women were taken prisoner, becoming the first female POWs since World War II.28 Then-Major Rhonda Cornum, an Army flight surgeon, was captured when her helicopter was shot down during a search and rescue mission. During her captivity, she was sexually assaulted, which again raised public concern about the roles of women in combat and the risks that they faced.29

Following Operation Desert Storm, efforts to expand the assignment of women were renewed by civil rights and women’s advocacy groups. Legislation enacted in 1991 called for the repeal of the statutory limitations on the assignment of women in the armed forces to combat aircraft and naval vessels and the establishment of a Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces.30 On November 15, 1992, the commission issued its report. Some key recommendations were the following:

- DOD should establish a policy to ensure that no person who is best qualified is denied access on the basis of gender to an assignment that is open to both men and women. As far as it is compatible with the above policy, the Secretary of Defense should retain discretion to set goals that encourage the recruitment and optimize the utilization of women in the armed services, allowing for the requirements of each military department.

- Military readiness should be the driving concern regarding assignment policies; there are circumstances under which women might be assigned to combat positions.

- Women should be excluded from direct land combat units and positions. Furthermore the commission recommends that the existing service policies concerning direct land combat exclusion be codified. Service Secretaries shall recommend to the Congress which units and positions should fall under the land combat exclusions.

- Current DOD and Service policies with regard to Army, Air Force and Navy aircraft on combat missions should be retained and codified by means of the reenactment of Section 8549 of Title 10, U.S. Code which was repealed by P.L. 102-190, Section 531 for the Air Force, and reenactment of the provisions of 10 U.S.C. Section 6015 prohibiting women from assignment to duty on aircraft engaged in combat missions, which was repealed by P.L. 102-190 for the Navy, and codification of Army policy.

- Existing laws and Service policies prohibiting servicewomen from service on combatant vessels should be repealed or modified, except for those applying to submarines and amphibious vessels.

- DOD should retain the risk rule [as explained above] as currently implemented. Navy policies which implement the risk rule should be modified to reflect the changes made [in the above recommendation].31

In addition, the commission recommended retaining the current policies prohibiting the assignment of women in special operations forces.32

Repeal of the “Risk Rule” and a New Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule

On April 28, 1993, then-Secretary of Defense Les Aspin released a memorandum directing the military departments to open more positions to women and establishing an implementation committee to review and make recommendations on such implementation issues.

Several months later, as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY1994 (P.L. 103- 160), Congress enacted language that

- repealed the prohibition on women serving on combatant vessels and aircraft,

- required the Secretary of Defense to ensure occupational performance standards were gender-neutral, and

- required the Secretary of Defense to notify the House and Senate Armed Services Committees 90 days before any policy changes were to be made concerning the assignment of women to ground combat roles, and, required the Secretary of Defense to notify these committees 30 days prior to the opening of any “combatant unit, class of combatant vessel, or type of combat platform” to women.33

In 1994, Secretary Aspin officially rescinded the “risk rule” and approved a new Direct Ground Combat and Assignment Rule, sometimes called the Direct Combat Exclusion Rule:

A. Rule. Service members are eligible to be assigned to all positions for which they are qualified, except that women shall be excluded from assignment to units below the brigade34 level whose primary mission is to engage in direct combat on the ground, as defined below.

B. Definition. Direct ground combat is engaging an enemy on the ground with individual or crew served weapons, while being exposed to hostile fire and to a high probability of direct physical contact with the hostile force’s personnel. Direct ground combat takes place well forward on the battlefield while locating and closing with the enemy to defeat them by fire, maneuver, or shock effect.35

Secretary Aspin further specified that these assignment policies and regulations may include restrictions on the assignment of women:

- where the Service Secretary attests that the cost of appropriate berthing and privacy arrangements are prohibitive;

- where units and positions doctrinally required to physically collocate and remain with direct combat units that are closed to women;

- where units are engaged in long range reconnaissance operations and Special Operations Forces missions; and

- where job related physical requirements would necessarily exclude the vast majority of women Servicemembers.36

Supporters of these changes noted that they would open more opportunities for women in the armed services. Critics saw these changes as putting women at greater risk since they removed the “substantial risk” of being captured from the definition of ground combat.

Women in Combat Zones: Iraq and Afghanistan

In the first decade of the 21st century, several situations evolved that highlighted the disparity between the policy prohibiting women from assignment to direct ground combat units and the roles actually performed by women. Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in 2001 and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) in 2003 were the first large-scale mobilizations of U.S. troops since Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm in the early 1990s. The nonlinear battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan blurred the distinctions between forward and rear operating areas, often placing support units in the proximity of active engagements. The public debate over the assignment of women was reinvigorated when three Army women were captured by enemy forces in Iraq and sustained injuries following the ambush of their unit.37 The women were assigned to Army’s 507th Maintenance Company which provided logistic support to ground units, and thus not a unit whose primary mission was to engage in direct combat on the ground.

Also, in 2005 the Army started moving towards a “Modular Redesign” for rotation, training, and readiness reasons.38 Under this concept, the Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) served as the basic large tactical combat unit of the Army.

These BCTs were supported by Multi-Functional Support Brigades. These support brigades were often collocated with the BCTs included noncombat personnel, many of whom were women. Such collocation appeared to some to be at odds with the 1994 policies on the assignment of women.

Because of the nonlinear and irregular nature of the battle in Iraq and Afghanistan, the definition of “direct ground combat” in the 1994 policy became less useful: what did “well forward” mean on a nonlinear battlefield, and how useful was the “primary mission” criteria when noncombat units regularly engage in direct combat to carry out their mission? In this environment, the Army and Marine Corps utilized women to search Iraqi females for weapons, and to patrol with foot soldiers, usually in door-to-door-type operations.39 Also, women were increasingly involved in convoy escort missions that came under fire40 and were embedded with special operations forces (SOF) in Cultural Support Teams that helped units deal with local Afghani females while operating in Afghan villages.41 In 2005, Sergeant Leigh Ann Hester, an Army soldier, became the first female soldier to be awarded the Silver Star since World War II and the first to be cited for close combat action.42

Concerns over the collocation and forward deployment of support units resulted in language being included in the House version of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2006. Under this law, if the Secretary of Defense proposed to make any change to the 1994 ground combat exclusion policy, or open or close military career fields that had been in effect since May 18, 2005, the Secretary must first notify Congress and then wait 30 days (while Congress is in session) before implementing any such change.43 In addition, the Secretary of Defense was directed to submit a report concerning the Secretary’s review of the current and future implementation of the policy regarding the assignment of women with particular attention to the Army’s unit modularization efforts and associated assignment policies.

In a 2007 report, the RAND Corporation noted while the Army was complying with the DOD assignment policy, it may not have been complying with the separate Army assignment policy.44 Further, the report stated

[w]e find considerable evidence that support units are collocated with direct combat units if the definition of collocation is based purely on proximity. However, if the definition of collocation is based on interdependency and proximity, the evidence is inconclusive.45

The report noted that hundreds of female Army members had received a Combat Action Badge, suggesting that the Army has recognized the combat service of women regardless of whether the women had been assigned in compliance with policy.46 While the RAND report stopped short of recommending that more assignments be open to women, the authors did recommend that assignment policies for women be redrafted to “conform—and clarify how it conforms—to the nature of warfare today and in the future.”47

Women on Submarines

While women have been allowed by law to serve on surface combatants in the Navy since the early 1990s, women have been barred by policy from assignments on submarines until just recently. The early arguments for not assigning women to submarine duty in were not related to the dangers of combat, but instead related to privacy and habitability issues in cramped spaces and cost concerns for retrofitting submarines to accommodate both men and women.48 As early as 2000, based on recommendations by the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS), efforts were made by the Pentagon to open up assignments for women on submarines.49 However, these recommendations met with some opposition from senior Navy officials and Members of Congress who cited cost concerns for berthing modifications, privacy concerns, the possibility of sexual misconduct affecting unit cohesion and effectiveness.50

As a result, language was contained in the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2001 (P.L. 106-398) that seemingly halted the Pentagon’s efforts. Essentially, this language prohibited the Navy from assigning women to submarines from May 10, 2000 forward until the Secretary of Defense submits to Congress written notice of such a proposed change and following a period of 30 days of “continuous session of Congress (excluding any day on which either the House of Congress is not in session)….”51

It was not until February 23, 2010, that Secretary of Defense Robert Gates notified Congress of a decision by the Navy to allow women to serve on nuclear submarines.52 In 2011, the Navy began assigning female officers to submarines.

In 2015 the Navy began accepting applications for assignment of enlisted women to submarines, and on June 22, 2015, announced a list of 38 female enlisted sailors that will begin training to convert to a submarine rating.53

Military Leadership Diversity Commission

The Duncan Hunter National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 200954 contained language establishing the Military Leadership Diversity Commission. Among its duties, the commission was to conduct a study and file a report regarding diversity issues in the Armed Forces with attention to the “establishment and maintenance of fair promotion and command opportunities for ethnic- and gender-specific members of the Armed Forces at the O-555 grade level and above.” In March, 2011, the commission released its report, From Representation to Inclusion: Diversity Leadership and the 21st-Century Military.56 Three of its recommendations were particularly relevant to the issue of women and combat.

Recommendation 9:

DOD and the Services should eliminate the “combat exclusion policies” (discussed later in this report) for women, including the removal of barriers and inconsistencies, to create a level playing field for all qualified servicemembers. The Commission recommends a time-phased approach:

- Women in career fields/specialties currently open to them should be immediately able to be assigned to any unit that requires that career field/specialty, consistent with current operational environment.

- DOD and the Services should take deliberate steps in a phased approach to open additional career fields and units involved in “direct ground combat” to qualified women.

- DOD and the Services should report to Congress the process and timeline for removing barriers that inhibit women from achieving senior leadership positions.

Recommendation 18:

As part of the accountability reviews, the Services, in conjunction with the Chief Diversity Officer (established in Recommendation 15), should conduct annual “barrier analyses” to review demographic diversity patterns across the military life cycle, starting with accessions….

The annual analyses should include:

- accession demographics;

- retention, command selection, and promotion rates by race/ethnicity and gender;

- analysis of assignment patterns by race/ethnicity and gender;

- analysis of attitudinal survey data by race/ethnicity and gender;

- identification of persistent, group-specific deviations from overall averages and plans to investigate underlying causes; and

- summaries of progress made on previous actions.

Recommendation 20:

… Congress should revise Title 10, Section 113, to require the Secretary of Defense to report annually an assessment of the available pool of qualified racial/ethnic minority and female candidates for the 3- and 4-star flag/general officer positions.

The Secretary of Defense must ensure that all qualified candidates (including racial/ethnic minorities and women) have been considered for nomination of every 3- and 4-star position. If there were no qualified racial/ethnic minority and/or female candidates, then a statement of explanation should be made in the package submitted to the Senate for the confirmation hearings.57

This last recommendation flows from the commission’s finding that the combat exclusion policy limits women’s opportunities to attain the highest ranks in the military. Retired Air Force General Lester L. Lyles who chaired the commission stated, “We know that [the exclusion] hinders women from promotion. [ … ] they’re not getting credit for being in combat arms, [and] that’s important for their considerations for the most senior flag ranks.”58

DOD Review of Combat Exclusion Policies

The concern for equal opportunities for women in military leadership motivated a further review of the DOD’s combat exclusion policies. Section 535 of the Ike Skelton National Defense Act for Fiscal Year 201159 mandated this review, stating

(a) REVIEW REQUIRED—The Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Secretaries of the military departments, shall conduct a review of laws, policies, and regulations, including the collocation policy,60 that may restrict the service of female members of the Armed Forces to determine whether changes in such laws, policies, and regulations are needed to ensure that female members have equitable opportunities to compete and excel in the Armed Forces.

(b) SUBMISSION OF RESULTS—Not later than April 15, 2011, the Secretary of Defense shall submit to the congressional defense committees a report containing the results of the review.

In February 2012, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) released its report. Some of the findings were that there was no indication that females had “less than equitable opportunities to compete and excel under current assignment policy,” and there were “serious practical barriers” to the full elimination of gender assignment policies. The report also acknowledged that, given the nature the modern battlespace, the collocation policy had become irrelevant.61 In the conclusion, it stated

The Department intends to:

1. Eliminate the collocation exclusion from the 1994 policy;

2. As an exception to policy, allow Military Department Secretaries to assign women in open occupational specialties to select units and positions at the battalion level (for Army, Navy, and Marine Corps) whose primary mission is to engage in direct combat on the ground;

3. Based on the exception to the policy, assess the suitability and relevance of the direct ground combat unit assignment prohibition to inform policy decisions; and

4. Pursue the development of gender-neutral physical standards for occupational specialties closed due to physical requirements.62

This statement served as the DOD’s official notification to Congress of the removal of the collocation restriction and the intent to implement exceptions to the Direct Combat Exclusion Rule.63 The revised policy allowed commanders to collocate support units with women assigned (i.e., in open occupational specialties) with ground combat units. The report suggested that these changes might have the benefit of expanding career opportunities for women, while increasing flexibility for field commanders to meet combat support mission requirements, and potentially reducing the operational tempo for men assigned to collocated support units by increasing the number of personnel available for assignment.

The Repeal of the Direct Combat Exclusion Rule and Recent Developments

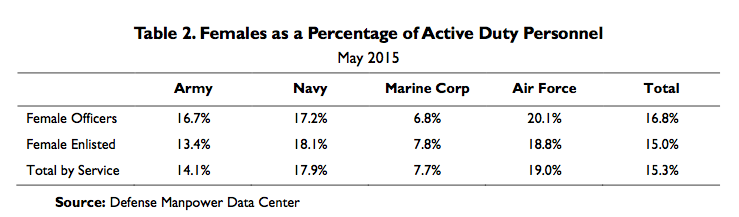

By 2013, the military departments had opened 14,325 positions to women under the new exceptions to the exclusion rule.64 Currently women account for 16.8% of the active duty officer corps and 15.0% of the enlisted corps across all DOD.65 The percentage of women varies across services (see Table 2). The Marine Corps and Army have a lower percentage of women in the service than the Navy and Air Force, but also have a higher number of combat arms positions that have historically been closed to women. For example, in 2013 the Army reported that approximately 237,000 positions were closed to women, with over 105,000 positions in artillery, infantry and armor occupations. The Air Force, on the other hand reported less than 5,000 closed positions.66

On January 24, 2013, then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta announced DOD was rescinding the Direct Combat Exclusion Rule on women serving in previously restricted occupations (i.e., combat). This policy change opened two categories of positions, previously closed combat arms occupational specialties and non-combat specialties assigned to combat units (e.g., a medic serving in an infantry company). The implementation of this policy change was to be guided by the following principles:67

Ensure the success of our nation’s warfighting forces by preserving unit readiness, cohesion, and morale.

Ensure all service men and women are given the opportunity to succeed and are set up for success with viable career paths.

Retain the trust and confidence of the American people to defend this nation by promoting policies that maintain the best quality and most qualified people.

Validate occupational performance standards, both physical and mental, for all military occupational specialties (MOS), specifically those that remain closed to women. Eligibility for training and development within designated occupational fields should consist of qualitative and quantifiable standards reflecting the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for each occupation.

For occupational specialties open to women, the occupational performance standards must be gender-neutral as required by P.L. 103-160, Section 542 (sic) (1993).

Ensure that a sufficient cadre of midgrade/senior women enlisted and officers are assigned to commands at the point of introduction to ensure success in the long run. This may require an adjustment to recruiting efforts, assignment processes, and personnel policies. Assimilation of women into heretofore “closed units” will be informed by continual in-stride assessments and pilot efforts.

The Secretary of Defense directed the military departments to develop implementation plans for the review of service-level policies and standards and to expeditiously move forward in the integration of women into previously closed positions.

As per the Secretary’s instruction, any recommendations to keep an occupational specialty closed to women will require approval by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) and the Secretary of Defense. The opening of these positions will likely have the largest impact on the Army, Marine Corps, and the Special Operations community where infantry, armor, artillery and other specialized combat positions were previously closed to women under the Direct Combat Exclusion Rule. The military departments are expected to complete their reviews and to notify Congress of their plans for integrating women into combat roles by January 1, 2016.

Key Issues for Congress

Any changes proposed by the DOD will likely be subjected to congressional scrutiny. Congress may accept any proposed changes or seek to subject such changes to certain modifications. Two key legislative issues that may arise are the validation and implementation of gender-neutral occupational standards, and laws requiring registration for Selective Service. Among the additional issues Congress may consider are equal opportunity, unit readiness and cohesion, and force structure and manpower needs.

“Gender-Neutral” Standards

One of the issues for Congress to consider with the opening of combat roles to women is how the definition of gender-neutral standards will be applied and how the standards will be validated. The military departments, in their respective women in the service implementation plans, have indicated that they will conduct research and reviews to validate the physical standards for all occupations (opened and closed). Congress has the authority to review the proposed changes, provide oversight for implementation, and to amend the definition of gender-neutral occupational performance standards as needed.

Definitions and Requirements

In the National Defense Authorization Act for FY1994 (P.L. 103-160 §543, as amended by P.L. 113-66 §523), Congress established requirements for gender-neutral occupational performance standards:

(1) GENDER-NEUTRAL OCCUPATIONAL STANDARD. The term “gender-neutral occupational standard”, with respect to a military career designator, means that all members of the Armed Forces serving in or assigned to the military career designator must meet the same performance outcome-based standards for the successful accomplishment of the necessary and required specific tasks associated with the qualifications and duties performed while serving in or assigned to the military career designator.

SEC. 543. GENDER-NEUTRAL OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE STANDARDS.

(a) GENDER NEUTRALITY REQUIREMENT. In the case of any military career designator that is open to both male and female members of the Armed Forces, the Secretary of Defense

(1) shall ensure that qualification of members of the Armed Forces for, and continuance of members of the Armed Forces in, that occupational career field is evaluated on the basis of an occupational standard, without differential standards of evaluation on the basis of gender;

(2) may not use any gender quota, goal, or ceiling except as specifically authorized by law; and

(3) may not change an occupational performance standard for the purpose of increasing or decreasing the number of women in that occupational career field.

(b) REQUIREMENTS RELATING TO USE OF SPECIFIC PHYSICAL REQUIREMENTS.

(1) For any military career designator for which the Secretary of Defense determines that specific physical requirements for muscular strength and endurance and cardiovascular capacity are essential to the performance of duties, the Secretary shall prescribe specific physical requirements as part of the gender-neutral occupational standard for members in that career designator and shall ensure (in the case of a career designator that is open to both male and female members of the Armed Forces) that those requirements are applied on a gender-neutral basis.

(2) Whenever the Secretary establishes or revises a physical requirement for a military career designator, a member serving in that military career designator when the new requirement becomes effective, who is otherwise considered to be a satisfactory performer, shall be provided a reasonable period, as determined under regulations prescribed by the Secretary, to meet the standard established by the new requirement. During that period, the new physical requirement may not be used to disqualify the member from continued service in that military career designator.

Review and Validation

All of the military departments establish testable minimum physical fitness standards for their personnel regardless of the military occupational specialty or career designator.68 These physical fitness tests are administered upon entry and annually thereafter and are intended to encourage a minimum standard of physical fitness and health across the military forces. The standards and scoring table vary by both age and gender to account for physiological differences. For example, a 22-year old male is required to run 2 miles in a maximum time of 17:30 in order to pass the Army Physical Fitness Test (PFT). The maximum time for a 22-year-old female is 20:36. In both instances, the individuals who achieve a passing time on the run receive the same score. The scoring tables differ under the principle that a women who is able to run 2 miles in 17:30 is, on average, more physically fit (in terms of muscular strength and endurance, and cardiovascular capacity) than a man of the same age who is able to complete the run in the same time.

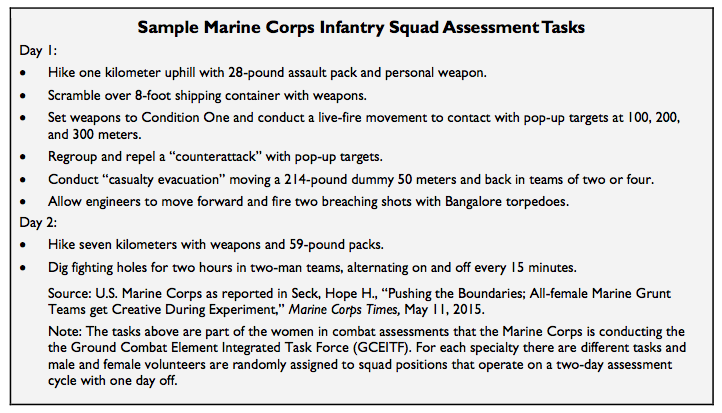

While all servicemembers must maintain basic physical fitness standards, the military departments also establish additional standards for entry into certain occupational fields based on the capabilities needed to complete tasks associated with that occupation. (See sample Marine Corps infantry squad assessment tasks in the below box.) Whereas basic physical standards described above are used as a mechanism to measure the servicemember’s fitness, occupational standards are used to measure the ability to meet job requirements. A basic interpretation of Section 543(1)(b) regarding physical requirements suggests there will only be a common outcome-based standard for each occupational career field and that men and women would be required to meet the same physical standards in order to be similarly assigned. It follows, for example, that if the occupation requires the servicemember to run 2 miles in 17:30 minutes, both men and women must meet that standard regardless of relative fitness levels.

Some have expressed concerns that the physical occupational standards and testing for certain career fields do not accurately reflect the actual job requirements and may be unnecessarily high, creating artificial barriers to women’s entry into some career fields. In the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (P.L. 113-291 §524), Congress gave further direction to the Secretaries of the military departments regarding the development and validation of gender-neutral occupational standards, requiring that the standards

(1) accurately predict performance of actual, regular, and recurring duties of a military occupation; and

(2) are applied equitably to measure individual capabilities.69

The first validation criteria would require evidence that the tested standard is predictive of the actual task required to serve in that occupational field. For example, one occupational requirement might be the ability to rappel down a rope from a helicopter in a certain amount of time. For practical reasons (i.e., cost, risk of injury, resource availability) it may not be in the best interest of the services to test servicemembers in a live environment. However, the number of pull-ups a servicemember can achieve may be predictive of their performance in rappelling. Under the criteria above, the services would be required to demonstrate both that rappelling from a helicopter is a regular requirement for the occupational specialty, and that the pull-up standard is an accurate measure of a servicemember’s ability to achieve that task regardless of gender.

While the focus for validating these requirements is on the military career occupations previously closed to women, the services are also evaluating whether standards should differ for other occupational specialties. Comments from General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff suggested that in validating requirements, they will be taking into account these issues70

as we look at the requirements for a spectrum of conflict, not just COIN, counterinsurgency, we really need to have standards that apply across all of those. Importantly, though, if we do decide that a particular standard is so high that a woman couldn’t make it, the burden is now on the service to come back and explain to the secretary, why is it that high? Does it really have to be that high?

The military departments are in the process of reviewing and validating performance standards and expect to have initial results by September of 2015. In addition to other review efforts, the Marine Corps and the Army have been conducting assessments of women’s performance in their elite infantry training schools. In 2012, the U.S. Marine Corps temporarily opened its Infantry Officer Course (IOC) and its enlisted Infantry Training Battalion (ITB) to female volunteers. As of May 2015, the end of the Marine Corps experiment, 29 female officers had attempted the course but none had graduated.71 The pass rate for women in the enlisted Marine Corps Infantry Training Battalion (ITB), which is regarded as a less strenuous course than the IOC, has been 35% over the testing period compared with a 98% pass rate for males entering the course.72

Likewise, the Army in 2015 opened its Ranger School to women for the first time for a one-time integrated assessment of female performance in the school. Of the 113 women who tried to qualify for the school, only 20 qualified, and 19 started the course.73 Of all those who start the course, the historical graduation rate at Ranger School is about 40%.74 As of May 2015, 8 of the 19 women had made it through the first assessment (Ranger Assessment Phase or “RAP week”) but did not pass the Darby Phase75 to qualify for the next step of training. Three of the eight women were invited to restart the Ranger School from day one in June 2015. On August 17, 2015, the Army announced that two women would be the first female soldiers to graduate from the Ranger School. The female graduates will be eligible to wear the Ranger tab on their uniforms signifying their achievement; however, they are not yet eligible to serve in combat occupations in the 75th Ranger Regiment.76

Implementation Concerns

Whether the standards are changed or stay the same as a result of the DOD’s review, many have concerns about the implementation. Although there are women who can meet and exceed the existing physical standards for males, forcing women to meet higher standards has been found in some cases to increase their injury and attrition rates.77 In the Canadian experience in which women were recruited for a 16-week infantry training course that was identical to the men’s course, the outcome was described as the “high cost of recruiting women that yielded poor results.”78 Additionally, a recent study of women in close ground combat from the United Kingdom Ministry of Defense (MoD) found that in initial military training, women have twice as much risk of musculoskeletal injury as men, and 15% to 20% higher rates of non-battle injuries in recent operations.79 However, this MoD report also acknowledged that women who would be capable of passing the close ground combat training might be more physically fit and less prone to injury than a cohort of women entering initial basic training.

Some are concerned that any change in standards would affect readiness and unit cohesion. Others argue that changing the current physical standards to account for male-female physiological differences would reduce unit effectiveness and ability to meet certain battlefield challenges. Some believe that even if the validation process shows that current standards for certain occupational series are inappropriate or unnecessarily high, any changes at this particular time would be perceived as a lowering of standards solely for the purpose of including women. For example, some are concerned that unit morale or cohesion might be affected if the integration of women under new standards creates the perception that the woman has not “earned” her place or that she is potentially replacing a more capable male soldier.80

Options for Congress

Women’s advocacy groups and other military and veterans’ groups are likely to closely monitor DOD’s review process and announcement for occupational standards. By law (P.L. 103-160 §543), DOD must notify Congress of changes to occupational standards that affect women’s entry into previously closed military career designators prior to implementing the standards:

(c) NOTICE TO CONGRESS OF CHANGES- Whenever the Secretary of Defense proposes to implement changes to the gender-neutral occupational standards for a military career designator that are expected to result in an increase, or in a decrease, of at least 10 percent in the number of female members of the Armed Forces who enter, or are assigned to, that military career designator, the Secretary of Defense shall submit to Congress a report providing notice of the change and the justification and rationale for the change. Such changes may then be implemented only after the end of the 60-day period beginning on the date on which such report is submitted.81

Congress may then postpone implementation, request further studies, reviews or justification, or allow the changes go into effect.

Selective Service

Many of those who emphasize equal rights say it is more difficult for servicemembers to advance to top-ranking positions in the armed services without combat experience. The inability of women to serve in combat roles is thus seen as a barrier to equal opportunity for promotion and selection for leadership roles.82 Some carry the argument further to say women cannot be equal in society as long as they are barred from full participation in all levels of the national security system.83 In their view, modern weapons have equalized the potential for women in combat since wars are less likely to be fought on a hand-to-hand basis. In this regard, properly trained women would be able to perform successfully in combat and exempting them from serving in combat is unfair to men.

This leads some to argue that equal access to combat jobs also obliges women to take equal responsibility for registering for selective service and being subject to the draft.84 Women are divided on this issue with some saying they should be allowed in combat but many saying they should not be forced into combat.85 Critics contend it would be unfair to permit women a choice that is not available to men and to make the choice available to both men and women would make it difficult for the services to function, especially in the event of war or national emergency. Given this argument, Congress may consider not only whether women who want to serve in combat roles are allowed to, but if women should be required to serve in combat roles.

Options for Congress

The question of whether women should be required to register for Selective Service under current law was previously decided by the Supreme Court in the 1981 majority decision in Rostker v. Goldberg. In the majority opinion, Justice William Rehnquist wrote:

[t]he existence of the combat restrictions clearly indicates the basis for Congress’ decision to exempt women from registration. The purpose of registration was to prepare for a draft of combat troops. Since women are excluded from combat, Congress concluded that they would not be needed in the event of a draft, and therefore decided not to register them.86

Congress has a number of options in addressing this issue. Congress has the authority to change draft registration laws (that currently pertain only to males) to include women.87 It has also been suggested that this issue can be made moot by terminating Selective Service registration. Another option for Congress might be to keep the draft registration laws unchanged, only requiring males to register. However, if Congress keeps the status quo, it is also possible Rostker v. Goldberg could be overturned in a future court ruling.

Other Concerns Regarding Women in Combat

Supporters of opening more occupational specialties and units to women note that women are already serving, fighting, and dying in combat. Others argue that opening more roles to women will result in a bigger pool of eligible recruits to compete for occupational assignments and could result in higher performing units. Some contend that unless all military roles are opened to women, women will not have equal career leadership opportunities.

Those opposed to changing restrictions on women in combat roles argue that a lack of combat experience does not adversely affect career advancement and promotions for women. They argue further that the progress of women is not the most important issue at hand, and contend that military readiness and national security has been and would further be weakened due to the presence of women in combat units.88 Those opposed note that close combat situations have and continue to exist and, on average, an all-male unit would be higher-performing in those types of engagements due to physical differences.

Both those in favor and opposed to women in combat acknowledge that there are likely social, cultural, and administrative barriers that would need to be overcome in order to implement full integration of women into combat units. Some of these administrative barriers (such as barrack/berthing assignments and separate toilet/shower facilities) have been overcome in the past as women were integrated into other occupational specialties and units.

In past gender integration efforts, the services have sought to assign senior female officers and non-commissioned to units prior to the assignment of more junior enlisted and attempted to avoid assigning only one women to a unit.89 Developing appropriate assignment policies may be more challenging as the number of women qualifying for combat roles may initially be very small as a percentage of the total force. For example, in the Marine Corps, where women account for only 7.7% of the total force, an infantry squad might consist of only one or two women out of twelve Marines, while other squads might have no women at all assigned.90

In terms of cultural adaptation, individuals who are accustomed to being in all-male units may offer some resistance to change. Some are also concerned that in small unit settings male-female relationships might develop that could affect unit cohesion and morale and result in reduced unit performance. Others note that women have been integrated into units for extended deployment periods with close-quarter environments for much of the recent history of the military. They also point to other factors, beyond gender homogeneity, that contribute to positive unit cohesion such as shared experiences, leadership, and command climate. Some also note that some of the same arguments about social cohesion were historically used by those opposed to the integration of other minority groups in the military (e.g., racial minorities and homosexuals) and that there is little or no evidence that unit effectiveness was reduced as a result of that integration.

Outlook for Congress

The military departments, as part of their women in combat implementation plans, are studying some of these social cohesion and morale concerns to understand the possible impact of change and to develop potential mitigation strategies. All DOD reviews and studies are expected to be completed by September 2015. The military departments are expected to present their results and findings to the Secretary of Defense for approval authority and the Secretary is required to notify Congress of DOD’s plans for integrating women into combat roles no later than January 1, 2016.

About the author:

*Kristy N. Kamarck, Analyst in Military Manpower

Source:

This article was published by the Congressional Research Service and may be accessed here (PDF)

Notes:

1 Defense Manpower Data Center, Defense Casualty Analysis System. GWOT includes Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn.

2 Bensahel, Nora, David Barno, and Katherine Kidder, et al., Battlefields and Boardrooms; Women’s Leadership in the Military and the Private Sector, Center for New American Security, January 2015, p. 9. The Silver Star Medal is the third-highest military decoration for valor to be awarded to members of the uniformed services.

3 Department of Defense, Defense Department Rescinds Direct Combat Exclusion Rule; Services to Expand Integration of Women into Previously Restricted Occupations and Units, Press Release, January 24, 2013.

4 The military departments were required to submit “Women in the Services Review (WISR) Implementation Plans” to the Secretary of Defense to outline their plans for opening closed occupations and positions to women by the 2016 deadline. The WISR implementation plans for the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force and U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) can be found at http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=16102.

5 Congress has the authority “To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces.” U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 8, clause 14.

6 James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, et al., Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, vol. 2, pp. 385-386.

7 31 Stat. 753; February 2, 1901.

8 P.L. 115; 35 Stat. 146; May 13, 1908.

9 P.L. 689; 56 Stat. 730; July 30, 1942. 10 P.L. 554, 56 Stat. 278, May 14, 1942.

11 “That there is hereby established in the Army of the United States, for the period of the present war and for six months thereafter or for such shorter period as the Congress by concurrent resolution or the President by proclamation shall prescribe, a component to be known as the ‘Women’s Army Corps’.” P.L. 110; 57 Stat. 371; July 1, 1943.

12 Women in the Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, Inc., see http://www.womensmemorial.org/H&C/ History/wwii.html.

13 Ibid.; Sixty-seven Army nurses and 11 Navy nurses were captured in the Philippines and held by the Japanese for nearly 3 years. Five Navy nurses were captured on the island of Guam were held as POWs for four months. One Army flight nurse was aboard an aircraft that was shot down behind enemy lines in Germany in 1944 and was held as a POW for four months.

14 P.L. 625; 62 Stat. 356; June 12, 1948: “Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of 1948.” 15 This legislation did not bar women from ground combat roles.

16 Janowitz, Morris, and Charles C. Moskos, Five Years of the All-Volunteer Force: 1973-1978, Armed Forces and Society, V, February 1979: 171-218.

17 P.L. 90-130; 81 Stat. 374; November 8, 1967.

18 P.L. 93-290; 88 Stat. 173; May 24, 1974. Prior to enacting this law, males who were not less than 17 years of age could enlist, while females were required to be at least 18 years of age.

19 P.L. 94-106; 89 Stat. 537; October 7, 1975. Women had already been admitted to the Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academies by administrative action. Women had also participated in the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Course (ROTC) as a source of commissioning between 1954 through 1958, but it was not until 1969 that women were again allowed into the Air Force Program, and in 1972 the Army and Navy opened ROTC as a commissioning source for women.

20 P.L. 95-97; 91 Stat. 327; July 30, 1977.

21 P.L. 95-485; 92 Stat. 1623; October 20, 1978.

22 U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Armed Services, Requiring Reinstitution of Registration for Certain Persons under the Military Selective Service Act, and For Other Reasons, Rept. 96-226, 96th Cong., 1st Sess., June 19, 1979.

23 U.S. Army Women’s Museum, available at http://www.history.army.mil/html/museums/showcase/women/ awm_text.html.

24 Raines, Edgar F., Jr., The Rucksack War: U.S. Army Operational Logistics in Grenada, 1983, Center of Military History: Washington, DC, 2010: 494.

25 Department of Defense, Report of the Task Force on Women in the Military, January 1988, p.10.

26 Combat jobs include those that directly confront and engage the enemy, such as infantry; combat-related jobs include those that support combat units in the field, such as those in support positions with combat engineers, as well as infantry and tank support units, including units that transport fuel, ordinance and ammunition.

27 The remaining positions were closed due to prohibitive living arrangements (12%) and special operations assignments (2%). The GAO’s study did not look at how this affected women’s advancement or promotion opportunities. U.S. General Accounting Office, Information on DOD’s Assignment Policy and Direct Ground Combat Definition, GAO/NSIAD-99-7, October 1988: 4. See also U.S. General Accounting Office, Women in the Military Impact of Proposed Legislation to Open More Combat Support Position and Units to Women, GAO/NSIAD-88- 197BR, July 1988.

28 Women in the Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, Inc., see http://www.womensmemorial.org/H&C/ History/wwii.html.

29 Sciolino, Elaine, “Female P.O.W. Is Abused, Kindling Debate,” New York Times, June 29, 1992.

30 P.L. 102-190; 105 Stat. 1365; December 5, 1991.

31 Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces, Report to the President, November 15,

1992.

32 For more information on special operations forces, please see CRS Report RS21048, U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF): Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert.

33 P.L. 103-160; 107 Stat. 1659 et seq.; November 30, 1993.

34 A brigade or its equivalent is a unit of approximately 3,000-5,000 persons.

35 Department of Defense, Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule, January 13, 1994. 36 Department of Defense, Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule, January 13, 1994.

37 Specialist Lori Piestewa became the first woman to be killed in the 2003 invasion of Iraq from injuries sustained in the attack. However, much of the attention focused on PFC Jessica Lynch after various conflicting accounts of her actions were published and reports suggested that certain injuries she sustained were the result of sexual assault while in captivity. Some pointed to this as an argument against women in combat roles. See U.S. Congress, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Misleading Information From the Battlefield: The Tillman and Lynch Episodes, First Report, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., September 16, 2008, H.Rept. 110-858 (Washington: GPO, 2008).

38 For more information see CRS Report RL32476, U.S. Army’s Modular Redesign: Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert.

39 Perry, Tony, “Women on Iraq’s Front Lines,” Los Angeles Times, November 13, 2008.

40 Wood, Sara, “Woman Soldier Receives Silver Star for Valor in Iraq,” DOD News, June 16, 2005.

41 Cronk, Terry M., “Cultural Support Team Women Serve with Distinction,” DOD News, April 30, 2015. 42 Fainaru, Steve, “Silver Stars Affirm One Unit’s Mettle,” Washington Post, June 26, 2005.

43 P.L. 109-163; 119 Stat. 3251; January 6, 2006. As described in this law, “such a change may then be implemented only after the end of a period of 30 days of continuous session of Congress (excluding any day on which either House of Congress is not in session) following the date on which the report is received.”

44 The Army policy defines direct combat to include the closing with the enemy in order to “destroy or capture the enemy, or while repelling the enemy’s assault by fire, close combat, or counterattack.” [Emphasis added.] Headquarter, U.S. Department of the Army, 1992, p. 5.

45 Harrell, Margaret C., et al., Assessing the Assignment Policy for Army Women, RAND, National Defense Research Institute, 2007: xvii.

46 The Combat Action Badge recognizes soldiers who have engaged the enemy, or were engaged by the enemy during combat operation. See http://www.army.mil/symbols/CombatBadges/action.html.

47 Harrell, Margaret C., et al., Assessing the Assignment Policy for Army Women, RAND, National Defense Research Institute, 2007: xxi.

48 Lorber, Janie, “Quiet Resistance to Women on Subs,” New York Times, May 12, 2010. 49 “Pentagon Panel Says Women Should Serve on Subs,” CNN U.S., May 26, 2000.

50 “Lawmaker moves to bar women from subs,” Washington Times, May 5, 2000.

51 P.L. 106-398; 114 Stat. 1654 A-136; October 30, 2000.

52 “Pentagon OKs Lifting the Ban on Women in Submarines,” Reuters, February 23, 2010.

53 Faram, Mark D., “First Enlisted Female Sub Selectees Announced,” Navy Times, June 22, 2015.

54 P.L. 110-417; 122 Stat. 4476; October 14, 2008; see §596.

55 Lieutenant Colonel for Army, Marine Corps and Air Force, and Commander for Navy and Coast Guard.

56 Military Leadership Diversity Commission, 1851 South Bell Street, Arlington, VA, 22202. Although the Final Report was issued on-line on March 7, 2011, the routing letter from the Chairman to the President and Congress was dated March 15, 2011.

57 Military Leadership Diversity Commission, Final Report, pp. 127, 129 and 130.

58 Daniel, Lisa, “Panel says Rescind Policy on Women in Combat,” American Forces Press Service, March 8, 2011. 59 P.L. 111-383; 214 Stat. 4217; January 7, 2011.

60 “At present, DOD’s Direct Combat assignment Rule (DGCAR) policy states that women can be assigned to all positions for which they are qualified, except within units below the brigade level whose primary mission is to engage in direct combat on the ground. The Army collocation assignment restriction further states that women can serve in any officer or enlisted specialty or position, except in those specialties, positions or units (battalion size or smaller) which are assigned a routine mission to engage in direct combat, or which collocated routinely with units assigned a direct combat mission.” http://www.armyg1.army.mil/hr/wita/.

61 Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (P&R), Report to Congress on the Reviews of Laws, Policies and Regulations Restricting the Service of Female Members in the U.S. Armed Forces, February, 2012, p. 4.

62 Department of Defense, Report to Congress on the Reviews of Laws, Policies and Regulations Restricting the Service of Female Members in the U.S. Armed Forces, February 2012, p. 4.

63 The report also stated that DOD gave notice of the changes commencing the congressional review timeline required in 10 U.S.C.§652, which means these changes became policy since Congress did not act on them.

64 Department of Defense, Memo from the Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the Secretary of Defense on Women in the Service Implementation Plan, January 9, 2013.

65 Defense Manpower Data Center as of January 2015.

66 Roulo, Claudette, “Defense Department Expands Women’s Combat Role,” DOD News, January 2013.

67 Department of Defense, Memo from the Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the Secretary of Defense on Women in the Service Implementation Plan, January 9, 2013.

68 Some occupational specialties require servicemembers to meet additional physical standards. 69 P.L. 113-291; 128 Stat. 1919; September 19, 2014.

70 Winn, Pete, “Gen. Dempsey: If Women Can’t Meet Military Standard, Pentagon Will Ask ‘Does it Really Have to Be That High,” cnsnews.com, January 25, 2013.

71 Seck, Hope H., “Last IOC in Marine Infantry Experiment Drops Female Officers,” Marine Corps Times, April 8, 2015.

72 Data provided to CRS by the U.S. Marine Corps in March 2015.

73 Mulrine, Anna, “Breaking Military’s Ultimate Glass Ceiling? Women start Ranger Training.,” The Christian Science

Monitor, April 30, 2015.

74 Lamothe, Dan, “Will the Army Open its Elite Ranger Regiment to Women? A Controversial Decision Awaits,”

Washington Post, August 11, 2015.

75 The Darby Phase is 15 days of intensive squad training and operations in a field environment that includes an

advanced obstacle course, airborne training, and a series of student-let and cadre-led patrols.

76 The 75th Ranger Regiment is a light infantry special operations unit specializing in a range of missions including direct action and personnel recovery. The Army has not yet announced whether it will allow women to apply for positions in this regiment or whether it will request a waiver to keep these positions closed.

77 Scarborough, Rowan, “Army may Train Women for Rigor of Front Lines, Studies Predict Injury, Attrition,” Washington Times, July 30, 2012.

78 Moore, Molly, Canada Puts Women on Front Line, Los Angeles Times, November 23, 1989.

79 United Kingdom Ministry of Defense, Women in ground close combat (GCC) review paper, December 1, 2014, p. B1, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/women-in-ground-close-combat-gcc-review-paper.

80 In studies of mixed gender units, some servicemembers attributed unit cohesion issues to differential standards between men and women. See for example Harrell, Margaret C. and Laura L. Miller, New Opportunities for Military Women; Effects Upon Readiness, Cohesion, and Morale, Santa Monica, CA, January 1997, p. 78.

81 Given that there are currently zero women in some career designators, an increase of one woman would be an increase of over 10%.

82 Bacon, Lance M., “We Need Their Talent,” Army Times, October 24, 2011. Odierno: “This is about managing talent. We have incredibly talented females who should be in those positions. We have work to do within the [Department of Defense] to get them to recognize and change.”

83 In July 2015 a teenage girl from New Jersey brought a federal class action suit against the Selective Service claiming the refusal to allow women to register is discriminatory now that women are eligible for combat roles.

84 Mulrine, Anna, “With U.S. Women Soon Eligible for Combat, the Draft Could be Next,” The Christian Science Monitor, October 28, 2014.

85 Lafond, Nicole, “Poll: Most Women Believe They Should Not Be Forced Into Combat,” The Daily Caller, February 7, 2013.

86 Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57 (1981). 87 50 U.S.C.§453.

88 See for example Center for Military Readiness, “Problematic Proposals in National Defense Authorization Act for 2015 (NDAA),” at http://www.cmrlink.org/content/women-in-combat/37616/ problematic_proposals_in_national_defense_authorization_act_for_2015_ndaa.

89 See for example the Navy’s policy on assignment of women to surface vessels (OPNAVINST 1300.17B, May 27, 2001) which requires a minimum of two female officers to be assigned (when no female enlisted are assigned) and a minimum of one female officer and one female Chief Petty Officer to be assigned to all gender integrated ships.

90 Seck, Hope Hodge, “All-Female Marine Grunt Team Gets Innovative During Combat Tests,” Marine Corps Times, May 2015.