Fighting For Libya’s Energy Wealth – Analysis

Libya’s economic conditions could turn sharply for the worse, as rival authorities vie to control rapidly shrinking national wealth. The struggle affects oil fields, pipelines and export terminals, as well as the boardrooms of national financial institutions. Combined with runaway spending due to corruption and dwindling revenue because of falling exports and energy prices, the financial situation – and with it citizen welfare – faces collapse in the context of a deep political crisis, militia battles and the spread of radical groups, including the Islamic State (IS). If living conditions plunge and militia members’ government salaries are not paid, the two governments competing for legitimacy will both lose support, and mutiny, mob rule and chaos will take over. Rather than wait for creation of a unity government, political and military actors, backed by internationals supporting a political solution, must urgently tackle economic governance in the UN-led talks.

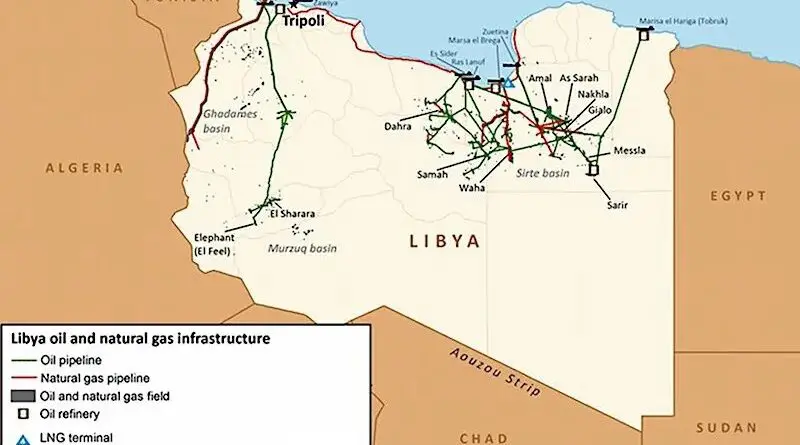

Since the Qadhafi regime fell in 2011, Libya has been beset by attacks on, labour strikes at and armed takeovers of oil and gas facilities, mostly by militias seeking rents from the fledging central government. Initially brief and usually resolved by government concessions, the incidents gradually took on a life of their own, in an alarming sign of the fragmentation of political, economic and military power. They show the power accrued by militias during and since the 2011 uprising and the failure of efforts to integrate them into the national security sector. The dysfunctional security system for oil and gas infrastructure presents a tempting target for IS militants, as attacks in 2015 have shown.

One aspect of the hydrocarbon dispute is a challenge to the centralised model of political and economic governance developed around oil and gas resources that was crucial to the old regime’s power. But corruption that greased patronage networks was at that model’s centre, and corrupt energy sector practices have increased. A federalist movement some consider secessionist controls a number of the most important crude-oil export terminals. It exploits the situation by pursuing its own sale channels, adding to the centrifugal forces tearing Libya apart.

This complicates efforts to resolve a political conflict that in July 2014 triggered a split between rival parliaments, governments and military coalitions – one based in the capital, Tripoli, the other in the east, and both with support from competing regional players. Convinced of its legitimacy, each fights to control key institutions. As the most important, the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) and the National Oil Company (NOC), are under Tripoli’s control, the internationally recognised parliament in Tobruk and its government in al-Bayda are trying to set up parallel institutions. The sides also contest the assets of the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA, the sovereign wealth fund), in international courts. In anticipation of a unity government, most regional and all other international actors with a stake remain committed to the established CBL, NOC and LIA. They understand that these institutions jointly represent upwards of $130 billion and have senior technocratic expertise critical to rebuilding the state.

The longer negotiations stall, however, the greater the risk the Tobruk/Bayda authorities (which consider the Tripoli-based CBL and NOC biased against them) will be able to create rival institutions or weaken the existing ones. At the same time, Libya’s once-significant wealth (derived almost entirely from oil and gas sales) is haemorrhaging, due to corruption and mismanagement. Combined with reduced crude-oil exports because of damage to production and export sites, pipeline and other infrastructure blockades and the sharp decline in international oil prices, this makes remedial action urgent. Poor economic management already causes some shortages of fuel and basic goods; a wider economic crisis like a sudden, uncontrolled devaluation of the dinar, would severely harm millions. This would likely cause new security crises, encouraging more predatory behaviour by militias whose salaries the state pays, increasing the importance of the parallel economy (notably smuggling) and spurring new refugee flows.

Even as UN-led negotiations for a Government of National Accord (GNA) continue, several steps should be taken, including at a minimum:

- reiterating international determination that there can be only one CBL, NOC and LIA, with a GNA to appoint their senior managers; and oil sales or related contracts outside official channels will not be tolerated;

- prioritising economic governance in the UN-led talks so as to secure agreement on short-term economic policy and interim management of key institutions. This should be done in a separate negotiating track, including representatives of both authorities and with the support of international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank;

- brokering of local ceasefires in the UN-led talks’ security track, or other channels where relevant, to increase revenues in the short term by allowing reopening of blockaded oil fields, pipelines and export facilities. Security arrangements for repair and reopening of damaged facilities should be negotiated in the longer term; and

- making the question of the armed groups guarding oil facilities another priority security-track topic. Some of these have considerable arsenals and allies across Libya and are largely autonomous, so cannot be ignored. Including these armed groups could also help improve the protection of oil and gas infrastructure against attacks by IS affiliates.

The slow progress of the UN-led talks on political questions should dissuade neither the belligerents nor the internationals from encouraging such interim steps. That Libya has kept, against all odds, a minimum level of economic governance and even briefly increased oil exports shows that interim economic arrangements are possible; they could even deliver political gains by building confidence and demonstrating that compromise can be mutually beneficial. But this needs a push from outside, the resolve of both local and international actors – notably regional powers that have oscillated between backing a political solution and supporting one side or another – to maintain the integrity of the financial institutions and perseverance from negotiators. Above all, it entails convincing the two sides they are fighting over a rapidly diminishing prize and would be better off agreeing to these steps so as to share a bigger pot.

For the full report, click here.